I love Peter Schjeldahl, The New Yorker’s art critic—he has such a good way with words. It’s the substance of his essays I have a problem with. I first lost faith in him as a Picasso critic in his review of the MOMA’s Matisse-Picasso show, when he eenie-meenie-mynie-mo’ed which painting was the best in show until he settled upon Matisse’s The Piano Lesson, because it “falls entirely outside Picasso’s range.” Sorry, but nothing Matisse ever did was beyond the range of the creator of a hundred styles. Now Schjeldahl takes some more potshots at the maestro in his review of the current Picasso show in Madrid (“Spanish Lessons”, June 19, 2006), which shows Picasso side-by-side with some of the Old Masters who inspired him. In his current offering, Schjeldahl labels Guernica as a “cartoon”, and follows with, “Picasso couldn’t help making this picture, like all his others, be about himself.” How, exactly? By allegedly bringing his women to tears, as if this would diminish the artist’s achievements, much less address the meaning of the painting. Schjeldahl prefers the realism, relative to Picasso, of Manet and Goya “in conjuring lived horror, with flowing blood and choking gun smoke”. Yet as Picasso said, “I have not painted the war because I am not the kind of painter who goes out like a photographer for something to depict.” Picasso’s political art was deliberately oblique and allegorical, and therefore more powerful.

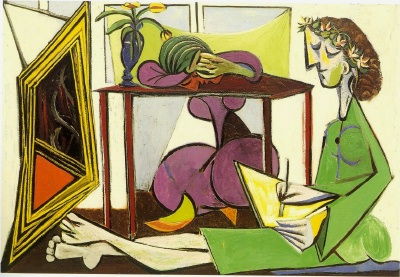

It’s easy to invoke the alleged “poverty of Picasso’s color”, if one focuses only on his black-and-white works. We need only consider the two recent expensive sales, still in our short-term memories, of the Boy with a Pipe and Dora Maar with Cat, or remember the many vivid paintings of Marie-Thérèse of the 1930’s such as the one shown below, for example, to conclude that Picasso’s mastery of color was second to none.

Or this, “Picasso had faith only in himself.” Sounds logical to me, since as even Schjeldahl concedes, “By general agreement, he was the best artist of the twentieth century.”In the end, Schjeldahl reminds me of my dear mother, who only liked Picasso’s Blue Period—a sure sign of a Picasso hater and of one who doesn’t even begin to understand his art.

Poor Peter Schjeldahl! You have taken on the role of the “Defender of the (Picasso) Faith” ready to pounce on heretics and less than total believers. Thinking of your zealous defense, I immediately went to El Greco’s Portrait of Cardinal Don Fernando Nino de Guevera, the Grand Inquisitor of Seville. Now that’s a colorist for you! Your statement that Picasoo’s mastery of color is second to none must certainly take this painting into account in any comparison. But I digress.

There are some things in Schjeldahl’s articles which are mean-spirited, but which you do not mention, such as his view that Picasso was “a figure of relatively wizened, sour spirit” — apparently because he did not have religious faith. This remark seems to imply that great color can only come from religiosity in the manner of Titian, Rubens, and Veronese. It is both narrow and inaccurate, when considering the color of Matisse (and my own contemporary favorite, Ronald Kitaj).

I have “oohed and aahed” with the best of them when viewing Guernica, but I must confess that I was not subsumed by it and it did not go to my gut as Manet’s and Goya’s executions certainly did. This may be my own shortcoming, but I am nonetheless reminded of the movie “Citizen Kane,” which many critics say is the best movie of all time, but which I would not even place on my top 20 list, Peter Bogdanovich notwithstanding. It is death in the abstract while Manet and Goya places death right in front of your eyes. What also captures and envelops me with the immediacy and emotion of death is Robert Capa’s great photograph of a falling and dying Spanish loyalist soldier a split second after he was shot (and perhaps, already dead). I am unable to share your view that Picasso’s art was more powerful because it was “deliberately oblique and allegorical.”

Your reference to Picasso as the “creator of a hundred styles” appears to me to be too hagiographical in the manner of referring to Mao as the “Great Helmsman” or to Kim Il Sung as the “Great Leader.” Why does a change in styles denote greatness? True Picasso did great “riffs.” But is this improvisational creativity necessarily greatness? Were his 100 styles invented by him or were they borrowed from other artists, many of whom were afraid to let him into their studios where he could see their own ideas and new styles and develop them better than they themselves could.

If I am to join your Picasso-ist commune I will need further convincing.

Best Regards, ALLAN

You’re beginning to remind me of Schjeldahl—I love your style but I disagree with your substance. Let’s stick with the basics. If we can’t iron out our differences over the color issue, which seems as obvious and clear-cut to me as I’m afraid it also does to you, we might as well simply agree to disagree. How about giving it a shot: please explain to me how you could possibly assert that the Cardinal is colored better than the Deux Femmes? I know you ventured a line on this subject, and I love how it reads, but please tell me that it’s only a start. I know that reasonable minds may differ, but we are such worlds apart on this point that I am curious weather a thoughtful exchange might serve to sway one or another of our steadfast opinions…. Call me simple-minded, but the El Greco has a flourish of red, where it belongs, i.e. on the guy’s cloak. The rest of the painting is rather drab. But the Picasso is seething with color everywhere, where it belongs and where it doesn’t—the faces are red and green, etc.!

Clever point “that great color can only come from religiosity”! I think it’s a valid inference in that context.

Guernica is far from my favorite Picasso. I love many of the prescripts and postscripts to it much more as individual works of art. But Guernica is monumental in size and in the political context of the times. I have seen enough images of “death right in front of your eyes” in photography and especially cinema that I am no longer moved by such realistic depictions in art. I prefer distortion and allegory in general (two of the main reasons I love Picasso I suppose, to realism), because, when well done, they afford an opportunity of greater creativity and originality. When well done, as in Picasso, the results can be transcendental.

You’re right—I certainly do not shy from hagiography with regard to my favorite painter. And, certainly, changes in styles do not denote greatness. But if every one of those 100 styles are great, as were Picassos, then the effect is incredible, not to mention historically unparalleled. Had Picasso only developed any one of these styles, he would still have been considered a great artist. Take Modigliani as an example of a one-trick pony, whose trick was similar to, but doesn’t begin to compare in quality, to Picasso’s Blue and Rose Periods, yet he’s considered one of the twentieth century masters, with sales now in the eight digits. Van Gogh and Gauguin were much better artists than he, but they, too, essentially had but one style. The many styles do more than just nourish our soul with beauty and poignancy—they provide a measure of the boundless, unprecedented creativity of this greatest artistic genius. -Kobi

In point of fact I disagree with the view that great color can only come from religiosity. Am I correct in understanding that you believe the Picasso Deux Femmes has stronger color than El Greco’s Defender of the Faith, who incidentally bears some comparison to you in your own actions as Defender of the (Picasso) Faith? Good humor, however, was not, I suspect, the Cardinal’s style, as is indicated in his stern visage, while you, however, appear to defend the Picasso canon in dismissing the corpus of pre- and post-Picasso works with an abundance of joviality. If indeed the side-by-side display of El Greco’s and Picasso’s works is meant to assert Picasso’s coloristic pre-eminence, I can do nothing but respectfully disagree. The admittedly good color in Picasso’s linear style simply does not overwhelm the viewer as does the representational richnessof El Greco’s Cardinal — even when it is used in the service of portraying a defensive, veangeful “true believer” out for the blood of heretics. I am reminded of my being vaguely ashamed in being attracted to Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will.”

OK, how do you feel about such widely-acknowledged supreme colorists such as van Gogh and Gauguin? Better than Picasso? In El Greco’s league? And, of course, why?

Our debate is over differences of degree rather than of kind. My all-time list of colorists would include, as well as Picasso, names such as El Greco, Kandinsky, Matisse, Rubens, Velasquez, Vermeer, Van Gogh, Renoir, the Dutch “still-life-ists. I also love the Fauvists; I think they were eclipsed far too soon by the rise of Cubism. Their corpus was not powerful, but their color was great. My opinion is not steadfast; part of me loves the word-play, part of me loves the playing of Devil’s Advocate — which, if it does nothing else, can nonetheless assist you in articulating your argument in response to unworthy parvenu such as me. . I think if I had to pick one series of work whose color transfixes me it would be the work of Kandinsky from 1909 to 1916. Recapitulating our diversity of opinion. I would say: “TRULY, Picasso is one of the greatest artist of all-time.” I think you would say: TRULY, Picasso IS the greatest artist of all-time.” I enjoy our discussions. It’s like being able to monopolize the time of Phillip Roth or Lionel Trilling.

Well, as long as you consider Picasso one of the great colorists, I suppose we can leave it at that!

Though I am flattered beyond belief, needless to say I should not be mentioned in the same breath as Roth and Trilling. You, maybe!