In the art world, just as everywhere else, there are facts and there are matters of opinion. And there are misinformation and disinformation. With Picasso, the relative truthfulness of alleged facts and factoids are all over the map. It’s your job to discern into which category belong your various sources of information. Let’s look at one extreme example, the most expensive Picasso ever sold to date, and let’s take but two extreme opinions in its regard. Garçon à la Pipe (Boy With a Pipe) was hammered at Sotheby’s New York in 2004 for $104.1 million. The editorial fallout was immediate and widespread. On the one hand, we have the claim put forth by the International Herald Tribune (May 8, 2004), “The picture is one of the greatest ever, perhaps the greatest,” by Picasso. In the opposite camp we have a pronouncement by John Richardson, one of Picasso’s foremost biographers, stating that the painting would not have made his top 20 Picasso list.

Interestingly, Richardson went on to say that no painting is worth a 100 mil. Coming from a world-class expert, that strikes me as a really funny opinion. So if a Stealth Bomber costs more than a billion, what, a Picasso is not worth a tenth of that, say its left wing? Richardson, of all people, should know that there’s no such thing in art as intrinsic (monetary) value, but rather that the monetary value of art is determined by whatever the market is willing to bear. Or at least what two runaway bidders are willing to bear….

By the way, like Richardson, Boy with a Pipe would not have made my top 20 list, or even my top 100. Possibly not even my top 500. Which is not to say that I don’t think it’s an exceptionally beautiful painting, but, rather, that Picasso painted many exceptionally beautiful paintings.

In this chapter, we will discuss a number of the potholes of which a collector should be aware in order to successfully circumnavigate them. But first the good news. As collectors, we should allow ourselves to lighten up a bit. After all, the print is a work on paper—it’s not, if you’ll pardon the expression, etched in stone! Though some sellers routinely hide significant imperfections of an impression from unwary collectors (we’ll get to this in the “bad news” section below), some sellers and buyers alike go the opposite extreme and obsess about every jot and tittle of the print in question. Some of these folks may have formed their attitudes decades ago, when Picassos were much easier to find. Those were the years of plenty, but now we’re well into the lean years. Time has passed, and, not only are his prints scarcer, they’re no longer as young and, in many cases, as unblemished, as they once were. Of course, one should certainly strive to purchase prints in as good condition as possible. But it’s time to put condition into perspective. Let’s delineate the types of condition issues that one encounters when hunting for prints and weigh these issues reasonably.

Part A: CONDITION

Ultimately, whatever the condition issues, they need to be weighed against the beauty, significance, scarcity, and price of the print. Let us begin by stating the prime directive: beauty is paramount. All too often I find clients lost in the trees of the condition details without appreciating the overall beauty of the forest. Condition flaws do affect the price of a print. But minor flaws have a small effect, typically not more than 10%, and truly trivial flaws have no measurable effect at all.

The main distinction to be made right away is between those flaws that mar the appearance of the print and those that don’t. If the flaw can’t be seen, because, for example, it’s on the back of the print or in the margins covered by the overlying matt, as a general rule, it doesn’t much matter. A second important distinction is between those flaws that are permanent and those that can be safely restored in the hands of a good print conservator (which inquiry and arrangements your friendly art dealer should be able to handle for you).

Condition issues can be classified as follows, in no particular order:

1. Poor impression (due to insufficient ink, wear of the plate, or stray printer’s ink),

2. Fading of the image and/or the signature,

3. Solarization—either darkening or lightening—of the paper in response to exposure to sunlight. (Whether the paper lightens or darkens depends on the chemical composition of the paper.)

4. Toning (darkening) of the print where it has been in contact with an acidic matt (also called “mat burn”) or an acidic hinge.

5. Backing and hinging issues,

6. Miscellaneous mishaps: dirt, stains, water stains, stray marks, tears, missing pieces, creases, thinning, and mildew.

Some of these flaws are permanent, but many can be completely restored, or nearly so. If you really look closely, for example, you might just see a faint line in the paper signifying a repaired tear. But should you really be looking that closely? At the time of purchase, sure. You want to know exactly what the condition is, because the price in some measure depends upon it. But, if you’ve decided to purchase the print and the flaws are truly insignificant, then don’t obsess about them once you’ve brought the print home. If the flaws mar the beauty of the print, then have the print restored. But, please, people, don’t forget to see the forest!

I could rail about the unimportance of trivial condition flaws till I’m blue in the face, but some collectors won’t care. Their minds are already made up. If the print is not in mint condition, they look elsewhere. Ultimately, in my opinion, it’s their loss. True, their collection is comprised of works in better condition than it may otherwise have been, but it’s proportionately impoverished in beauty.

Now let’s examine the various types of condition issues in a bit more detail:

1. IMPRESSION: As mentioned earlier, in this sense impression is a technical term referring to the ink that is “impressed”, or applied, under the pressure of the printing press, to a sheet of paper. The quality of the impression is related to whether the print took on just the right amount of ink to display the image optimally.

With modern printing techniques and the small edition sizes of all of Picasso prints, even the comparatively larger sizes of two or three thousand, impressions are almost always fine. Generally speaking, when it comes to Picasso’s prints, impression is a non-issue. (The principal exception to this rule, La Suite des Saltimbanques, is discussed below.) Of course, at times there are variations from one impression to another. These variations may affect the entire print or just a section of it. Often one can appreciate them only when given the opportunity to compare two impressions of the same print side by side. Without the benefit of this unlikely comparison, impressions may still at times seem a bit dull due to an insufficient amount of applied ink. Chances are the beauty of such a print will not leap out at you as much—your aesthetic subconscious, as I have learned from experience, automatically factors in the quality of the impression, at least to any meaningful extent. You’ll make your purchase decision based in large measure on your subjective evaluation of the print’s beauty, and that’s as it should be.

In addition to small edition sizes, one of the main reasons the vast majority of Picasso’s prints tend to have fine impressions is steelfacing. Steelfacing is a process by which iron is electroplated onto the soft copper plate in order to strengthen it, thus enabling hundreds, or, depending upon the type of print, even thousands of impressions of equal quality. Impressions prior to steelfacing should be better than those after. In many cases with Picasso prints, there are a few impressions prior to steelfacing. In some cases, the entire edition of a print may not have been steelfaced. The impressions prior to steelfacing make more of a difference with the type of intaglio print (see definition below) known as drypoint, which is a type of engraving. In André Beguin’s words,

“Whereas engraving with a graver or burin cuts metal out of the plate and etching removes metal by dissolving it, the drypoint technique only displaces the metal on the plate. In drypoint the metal surface is scratched, gouged, punctured, and scraped but the metal is not removed, it is just pushed to the side, forming a kind of curl. Thus the lines will present a metal burr which, when looked at through a magnifying glass, shows up as a kind of broken metallic wave. This burr must be kept intact on the plate since it is this element which characterizes the technique when it is printed. In fact, drypoint owes its particular results to the ink being caught both inside the lines as well as in the burr around the lines.”

Well, I’ve tried my level best to limit the use of technical jargon, but, since it will keep coming up, I suppose a definition of “intaglio” would be useful to you. Intaglio printing is a printing technique in which the design is cut into the plate rather than protruding from it. Examples of intaglio printing include etching, engraving, aquatint, and drypoint. Examples of the opposite technique, in which the part of the plate that gets inked is in relief, or sticks out, are woodcuts and linoleum cuts.

As a practical matter, since it is so famous, the print in which the absence of steelfacing makes the greatest difference is arguably Le Repas Frugal (The Frugal Repast, Bloch 1, see chapter 5). The rare, early impressions of this etching with scraper obtained prior to steelfacing fetch five to ten times as much as the impressions after steelfacing. Only part of the difference is attributable to the absence of a signature on the impressions after steelfacing. The majority of the difference in price is related to the much richer, darker quality of the earlier impressions. The same can be said of the difference between pre- and post-steelfacing in the remainder of The Saltimbanque Suite.

In addition to steelfacing, the type of paper can influence the quality of the impression. Some types of paper take up more ink than others and hence yield a richer impression. So-called “Japan” (or japon) paper is one such example. Many Picasso prints included a few impressions on Japan as a part of the complete edition and generally command a premium.

The quality of the impression in Picasso’s prints varies most in the first fifteen prints in the Bloch catalogue raisonné. Vollard published and cleverly packaged Picasso’s first print series as La Suite des Saltimbanques. These etchings and drypoints were printed by Fort, whose efforts were spottier and less consistent than Picasso’s successive printers. Certainly the few impressions pulled prior to steelfacing are usually the very best, but the high prices they fetch reflect their rarity and beauty. But even following steelfacing there is great variability in the impressions. Some are printed much more deeply than others, and some have much more plate tone than others. And one should not categorically assume that the impressions on “Japan” laid paper (about 10% of the edition) are better than the rest on van Gelder wove paper. Although it is true that the Japan rice paper takes the ink better than wood-pulp paper, the success of the printer’s efforts in pulling each impression trumps the paper type in determining the quality of the impression. Thus, the Saltimbanques must be closely and directly examined in order to assess the quality of each impression. Digital and printed images are largely insufficient to make the case. And the difference in the quality of the impressions is not just academic—poorly printed impressions look flat, in contradistinction to the richly printed ones, which look wonderful and dramatic.

As for stray printer’s ink, hey, it happens. A tiny amount of extra ink here or there, usually appreciable just when in the margins, doesn’t really matter. In general, if the print wasn’t printed well, it wouldn’t have been offered for sale. Picasso, his printers, and his publishers exercised a reasonable amount of quality control. In general, I feel, if it was good enough for Picasso, it’s good enough for me.

2. FADING: All prints and signatures (apart from those in graphite or lead pencil) fade due to sunlight and heat, so valuable prints should be protected. Thankfully, black, the flavor that most Picasso prints come in, also happens to be the color that is the most resistant to fading.

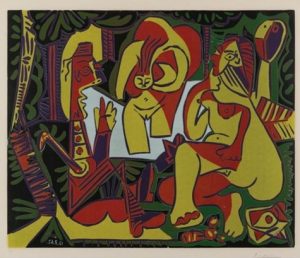

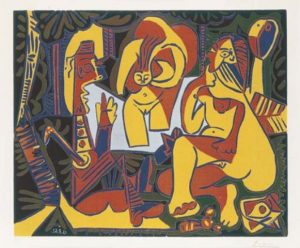

It is likely that susceptibility to fading may vary between the pigments used for different printing media. In other words, it is likely that the chemical composition of the linocut colors is rather different than, say, lithographs and aquatints. For example, the violets and royal blues of Picasso’s linocuts fade to light blue, then gray, then white (provided there are no underlying colors). But the violets and purples of his lithographs fade to gray and then to brown. But, for most practical purposes, when discussing fading, we’re talking linocuts. Apart from several nice lithographs of Francoise Gilot, several unsigned aquatints of Dora Maar, and several miscellaneous but barely colored lithographs, mostly in ochre, most of Picasso’s other colored prints are insignificant designs and won’t be belabored here. Fortunately, since they’re more plentiful, the colors in Picasso’s inocuts are considered more colorfast than in his lithographs.

The susceptibility to fading of all of the colors of Picasso’s linoleum cuts can be graded as follows, in more or less increasing order: black < gray, light blue, green, turquoise < red, orange, yellow < brown, beige < purple/violet (which Brigitte Baer terms violet foncé) < royal blue (Baer’s bleu clair). Strangely, in certain linocut editions the yellow is more evanescent than the red, and in others the reverse is true. I don’t know the chemical factors contributing to this paradox but feel that an impression of a given print should therefore best be compared to other impressions of the same print. There is certainly more to be learned before we can be definitive about the above hierarchy.

Since most of Picasso’s colored prints are linocuts, a few extra words about their colors are in order.

Right off the bat, there are epistemological obstacles. Study of the colors in textbook illustrations is problematic primarily for two reasons: they are often photographically distorted, and some of the textbooks, even Baer, the most authoritative reference, seemingly photographed faded impressions. As for seeing impressions in the flesh, you never know whether a given impression has faded unless you’ve seen one with deeper colors in the flesh, or trust that the deeper colors you’ve seen in a reference book are accurate. Unfortunately, the colors tend to be rather distorted in the most common linocut reference book, Linoleum Cuts: The Mr. and Mrs. Charles Kramer Collection [at] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, known as Kramer for short. The large-format book published by Abrams, Picasso Linoleum Cuts: Bacchanals, Women, Bulls & Bullfighters, has accurate colors, but it is limited to the linocuts of 1959.

It’s worth mentioning the relative colorfastness of the light blue Picasso used in a few prints. (Of these, I’m particularly fond of Femme Accoudée, B922). Baer terms this light blue blanc crème sur fond uni noir (creamy white on a black background), referring to the fact that it resulted from printing a white design on top of a black background, surprisingly yielding a very pleasing light blue or blue/gray tone. Even when it has faded somewhat, it’s still a lovely hue.

The next blue in Picasso’s linocut palette is more problematic. Baer terms it variously bleu clair (light blue), in the colorful version of Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (B1027) and Danae (B1084), or bleu gauloises (Gallic blue, whatever that means, as in the lovely Le Chapeau à Fleurs, B1149). There may be differences between the two, as the background blue in the rare unfaded impression I’ve encountered of Danae has a decidedly purplish or violet hue, whereas the deepest blue I’ve encountered in B1027 and B1149 would best be described as royal blue, without so much as a hint of purple or violet.

The problem is that bleu clair is a misleading term, because it is much darker than anyone’s reasonable definition of a light blue should be, as far as I’m concerned. It is certainly not nearly as light as the blue-on-black. It falls between the white-on-black at one extreme of the continuum of light to dark blue, and the purple/violet that falls at the other extreme.

So let’s now turn to that deep purple/violet before we lay the blues to rest. I had once thought that this color was as evanescent as the royal blue (bleu clair), but it seems that I was wrong. What convinced me was a comparitive analysis of several variably faded impressions of Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (B1027). Here’s one that’s suffered just enough solarization to wipe out the royal blue in the pond, but leave the purple (which Baer terms violet foncé, or dark purple) intact:

A little while longer in the tanning salon, and the purple has turned to a solid blue:

Where does it go from here? I shudder to think of it. Bear in mind that, at the time of this writing, it’s been over half a century since these proofs were pulled, and during most of that time folks just didn’t properly care for their prints. Hopefully, with proper ultraviolet retardant glazing, we can forestall the ravages of the sun sufficiently, at least during our lifetimes and, with luck, that of our children’s.

There are five measures which one can take to minimize the occurrence of fading:

a. Protect the print by, for example, placing it in a drawer and bring it out for an occasional viewing.

b. Avoid sunny spots when choosing where to hang the print. (Admittedly, these first two options are not entirely satisfying.)

c. Prevent exposure of the print to excessive heat.

d. Frame the work with ultraviolet-retardant glazing, either glass or OP3 acrylic, an abrasive-resistant acrylic. You should do this with every Picasso. I recommend that you avoid low-glare glazing, because it will kill the look of your art. Low-glare glazing compared to regular glazing is like frosted Scotch tape to clear Scotch tape. The exception to this rule is the so-called “Museum Glass” (trade name of Den Glass), which costs much more, currently several hundred dollars, but which retards both glare and ultraviolet light without diminishing the appearance of the art. I find that the eye naturally ignores the glare, and when you’re alerted to it, you’ll find yourself moving to a better vantage point. Another disadvantage of the OP3 non-glare acrylic is visibility will dramatically diminish the further you go to the side of the art.

A newer product on the market is Optium Museum Acrylic by Truvue, which I now use. It is the most expensive product yet, but combines the advantages of plastic with low-glare and also non-static properties. If you don’t mind paying hundreds of dollars just for the glazing, this is probably the way to go.

What exactly are the advantages of plastic over glass? Essentially, there are two. Plastic is not as heavy, which makes the frame easier to hang and perhaps less susceptible to falling off the wall. More importantly, Acrylic is shatterproof, whereas broken glass can ruin your art, either in shipping or in the event of an accident on your wall. Glass shards can scratch your art, create holes in it, and even tear it, possibly beyond repair.

As for cleaning acrylic, our trusted framer recommends a product named Brillianize (http://www.brillianize.com/index.html).

e. Apply an invisible, ultraviolet-retardant film onto your windows. Such films are widely commercially available, can be installed by their vendors, and have the added benefit, for those who live in a warm clime, of lowering the temperature in the room, thereby increasing your comfort and lowering your air-conditioning bill. (We found that the product called Sterling 60, manufactured by Panorama Designer & Safety Films, best fit our needs.)

Most of the fading that has already occurred with Picassos you’ll encounter is likely attributable to the absence of UV protection, both on the glazing of the frame and, even on the windows of the structure where the print had been displayed. Neither product has been on the market for all that long, certainly not during Picasso’s lifetime. Use of the now readily available, proper display techniques will limit, but not completely eliminate, future fading, and should be encouraged.

Curiously, one particular linoleum cut deserves singling out, because its fading characteristics are happily atypical. I’m referring to Danae (Bloch 1084, see the figure in Chapter 5). The violet in the background was inked over four other colors. When it fades, as it readily does, instead of turning into the dull brown to which purple usually fades, this violet becomes an appealing light blue, more homogeneous but otherwise very similar in hue to the light blue of the foreground. This light blue, identical to the light blue that Picasso used in a few other linocuts, seems rather colorfast. The reason may be attributable to the fact that the blue does not result from the use of a single pigment, but rather from the superimposition of an off-white pigment onto black. Why this should appear blue is a chemical mystery, but Picasso or his printer Arnera must have discovered this and been pleased with the result.

3. SOLARIZATION: Solarization refers to excessive exposure to light, especially in the ultraviolet range, though other wavelengths are contributory. Ultraviolet light derives from sunlight and fluorescent lights. A print that has been altered by sunlight is commonly termed “light-struck”. Depending on the type of paper, exposure to sunlight can either darken or lighten the paper. It does so in a homogeneous fashion and generally not to a large degree, so that it does not significantly detract from the beauty of the print. Plus it is generally completely restorable.

The way to minimize solarization is to frame your print with ultraviolet protection by following the same steps discussed above with regard to fading.

4. TONING, or MAT BURN: Toning, or darkening of the print due to contact with an acidic mat, also known as mat burn, is commonplace, despite the fact that it is completely avoidable. In years past, the predations of acidic mats were not well known, but today any decent framer knows about it. Acid-free mats cost a little more, but the difference is trivial given the value of your Picasso. Every Picasso in acidic matting should be removed from it. Period. Toning does not affect the image, unless so severe that even the front of the print has reacted to the acidity of the back mat. This is an infrequent occurrence, but will increase in prevalence as the years go by for prints not removed from acidic mounts. Toning is largely restorable, depending upon the extent.

5. BACKING AND HINGING: Backing and hinging create problems that vary in extent, but are both related to glue. Gluing of the print on another, typically stronger, surface is termed “backing” or “laying down”. Affixing the entire print to another sheet of paper or other material is an unfortunate event that lowers the value of the print. Thankfully, this practice is rarely down. One should be especially concerned about whether the “backing” of the print (i.e., the surface that the print was laid down upon) or the glue that was used to achieve this, is acidic, because, over time, the acidity will darken the print. It’s helpful if you happen to know whom the print has slept with and for how long. The usefulness of such knowledge applies equally to the backing of laid-down prints and to the front and back mats (see below) with which the print is in contact. Clearly, if you can determine that the print has been laid down (or matted with the same mat) for decades and it has not darkened over time, you can feel secure that there is no significant issue.

The acidity of the backing can easily be tested by applied a pH pen to it. The glue used to achieve the laying down, of course, is not accessible to such testing. If you’ve determined that the backing is acidic, you may inquire with your trusty conservator, or ask your dealer to inquire with his, whether the backing can be safely removed. This may or may not be possible.

By the way, “laying down” a print should not to be confused with “laid paper”, which is a descriptive term for one of the ways hand-made paper is produced.

Hinging is one of two ways of mounting a print within a mat; the other is using plastic corners. Hinges and hinge glue as well as plastic corners are available in acid-free varieties. When hinges have been removed, certain problems can result, such as hinge remnants, hinge glue remains, or thinning of the paper incurred when the previous hinges were forcibly and improperly removed. Hinging issues typically cannot be seen on the front of the print, with two exceptions: a. someone has ignorantly affixed the hinges to the front of the print (rare, but I’ve seen it), and b. the acidity of the hinges and/or their glue has reacted with the full thickness of the print.

The proper way to hinge prints is with mulberry paper glued with one of several types of water-soluble, acid-free glue such as wheat paste. This is the preferred method because such hinges and their glue are readily removable and, if removed correctly, leave no traces on the print. If you like the look of “floating” prints, i.e. the sheet of paper is visible in its entirety with any overmat, then this is the way to go.

If you prefer to cover all or part of the margins with the overmat, you could choose between mulberry hinges and plastic corners. The main disadvantage of plastic corners is that they could tear your print if mishandled. The disadvantage of the hinges is that they may need to be removed for a finicky collector, but that is more an art dealer’s problem than a collector’s. Unless of course you happen to be that finicky collector.

6. MISCELLANEOUS MISHAPS: These include dirt, stains, water stains, stray marks, tears, missing pieces, creases, thinning, and mildew. All of these defects are typically restorable. A couple of words of clarification: Thinning, or “skinning”, of a print may occur when such things as hinges, dirt, or stray marks are improperly removed and some of the paper is removed in the process. This is largely restorable with the application of methyl cellulose. Mildew may chemically react with iron impurities in the paper and may produce brown spots known as “foxing”. Foxing, which has been likened in appearance to measles on paper, is generally restorable.

7. TEACHING MOMENTS: Please see the blogpost Unnatural Disasters: The Perils of Paper for two examples of what can go wrong with conservation and what you can do to prevent such mishaps.

Part B: AUTHENTICITY

What’s even more fundamental than the condition of the print is whether or not it’s real. In other words, did the artist who purportedly made and signed it really make it and sign it? If so, it’s an original print with an authentic signature. If not, it’s not.

In actuality, there is a gray zone, at least when considering printmaking through the ages. In modern and contemporary art, the artist himself typically draws or cuts the design onto the template, be it copper, stone, linoleum, etc., from which the print will be pulled. Historically, however, most artists just drew the designs, and craftsmen copied the designs using their own hands, not the artist’s, to carve the templates. For example, woodblock prints achieved their epitome, both in terms of beauty and technical complexity, in eighteenth and nineteenth century Japan. Yet there is but one Japanese woodblock printmaker of the late eighteenth century who is known to have done it all, from soup to nuts. Yet this fact in no way devalues the worth of Japanese prints. Not so in modern art. We collectors typically want to know that we are buying a piece of the artist, i.e. the product of his own handiwork. In modern art, the term “original print” means that the artist drew or incised the image with his own hand, resulting in a template from which the print was directly pulled. No one else copied the image in the process of producing the print.

So now for the bad news. The eight-hundred pound gorilla in the room is art fraud. Just as patients find it difficult to evaluate the competence of their medical provider, often relying on his appearance or bedside manner since they lack the tools to assess his actual ability, often until it’s too late, many art collectors don’t even know where to begin, much less which questions to ask.

It doesn’t much matter if one simply wants to decorate a room with reproductions. There’s nothing wrong with posters in your college dorm room, or even in your home. Even with all the money in the world, some people, notably Bill Gates, content themselves with photocopies, which in Bill’s case are high-tech video projections which he can change at will. But some of us like to own original works of art by our favorite artists, and that’s where the problems begin. The opening quote of Richard Polsky’s hilarious book, I Bought Andy Warhol, discreetly attributed to an “anonymous” art dealer, says it all, “Sometimes I lie, but this time I’m telling the truth.”

Most people who buy “works of art” actually buy prints of well-known art. Many collectors of fine art also buy prints, primarily because prints are more available and more affordable than one-of-a-kind works. Is there a difference between these two types of prints? Apart from serious collectors, it is amazing how few buyers even know the definition of the term. Even fewer realize that most of the prints of works by famous artists in the marketplace are actually forgeries. The term “print” has a number of meanings, so let’s start with a basic definition. There are essentially two types of prints: original and reproductive. A reproductive print is at it sounds: a reproduction, usually involving a photograph or stencil, of a work of art. It typically has little value. An original print, in general, is the end-product of one or more techniques in which the artist has created a design expressly for that print and, in general, is the handiwork of the artist himself. The artist creates the design directly on some sort of plate (copper, stone, etc.) or in some cases he or his assistant transfers the design onto the plate. The print is then produced by applying paper to the inked plate. The print is not dependent upon any precedent, more original work. Although there may be related drawings or paintings, there is no earlier work of art from which the print has been directly derived. The plate, although interesting, is not the finished work of art.

Another semantic source of confusion is easily clarified, namely the distinction between original and unique works of art. An original print is not unique provided that the printer has printed more than one impression of it, as is usually the case. It is nonetheless original!

The ambiguity of the word print enables the shady dealer to cleverly craft the language by which he describes his print in order to technically avoid committing a fraud, yet still deliberately mislead the unsuspecting buyer. Exotic names for the printing technique have emerged just to heighten the buyer’s credulity, such as giclée and pochoir. Sounds authentic, huh? But giclée is a fancy name for a photograph of an art piece, and pochoir just means stencil in French. One needs to know, for example, that Picasso himself never used pochoir or any other related process such as silkscreen or serigraph in creating his prints. The matter, however, is complicated by the fact that he, like Matisse, Miro, and others, occasionally authorized and at times even hand-signed reproductions of his art. In Picasso’s case, the reproductions he signed were “original” prints made by other artists based on his oil paintings or drawings. These prints go by the peculiar termed “afters”. To be clear, these are original prints only in a limited sense, in that a no-name (and usually unnamed) artist created them from scratch, but they are not original prints by Picasso. These prints are not without value, especially because they tend to be printed in nice colors, but in general they have much less value than his original prints (though some Picasso “afters” now sell in the low five figures–we, however, don’t deal in them). By far and away the most notorious of these artists was Salvador Dali, who, to mention but one of his excesses, was known to have even signed blank sheets of paper and sold them to the highest bidder to do with them whatever he wished.

Not knowing any of this, when I first started collecting Picassos during my medical residency in Manhattan in the early eighties, I one day came across one of Picasso’s weeping women, in color, in the storefront window of an art gallery for $2200. It looked too familiar, and I couldn’t believe it was original at that price, even twenty-five years ago. But the owner insisted it was good. Being relatively inexperienced and not yet possessing the requisite reference books, I couldn’t prove otherwise. So I made the guy a deal: I’d give him a post-dated check for the full amount, take the piece to the Museum of Modern Art for authentication, and return it the next day in exchange for my check if it wasn’t real. Of course it turned out to be a mere photograph, in this case of a peri-Guernica oil wash and ink on paper. Far from offering an apology upon returning my check, the proprietor just feigned surprise. From this I learned for the first of many times that it is in the dealer’s best interest just to play along. He knows you’d think you’d caught him red-handed if backs down, and if he doesn’t, he’s betting you ultimately won’t bother with the authentication, having been convinced of the authenticity by his very willingness to let you seek it!

Fast forward two decades to just last year, when an ad for a traveling art fair caught my eye by advertising, among other things, “original Picasso lithographs”. My skepticism was heightened when the proprietors failed to answer the specific questions with which I phoned them in the week prior to the fair. But since the venue was just a short walk from my house, I thought I’d check it out, if only for comic relief. I espied a well-known Picasso painting, here photographically reproduced and not badly framed. Having seen no other Picassos at first glance, I approached the manager of the show and said, “You advertised original Picasso lithographs. Apart from the obvious fake over there, do you have any real Picassos?” Ignoring my comment, she directed one of her lackeys to point out the other dozen or so “Picassos” to me. My favorites were framed photographs of Picasso’s ceramics. Several hundred dollars would buy you not only a genuine Picasso but also a “Certificate of Authenticity”, generously pasted to the back of the frame and spelling out that you had purchased an “original ceramic by Picasso”! Now, I don’t know about you, but I always thought that ceramics were three-dimensional objects made of, yes, ceramic.

What about Internet auction sites? I glance at the Picasso listings from time to time just to see what’s out there. It appears to me that the vast majority of the Picasso prints, drawings and paintings on that site are fakes or forgeries. My favorite find was two copies of the same Picasso lithograph selling on eBay at the same time, one for $7500 and the other for $7,500,000. Both were forgeries of a real lithograph worth even less than the lower of the two prices. How can I be so sure? The sizes were wrong! The easiest way to discern a forgery is by the size. Most Picasso forgeries are simply pages removed from a coffee table book and are almost always different in dimensions that the original works. Although the precise dimensions of most famous artists’ creations are readily available, how many buyers know to look them up, or even where to look? And one shouldn’t be fooled by the presence of plate marks. Some forgers cleverly press a plate onto the periphery of the print to resemble those often seen in original etchings.

I have a weak spot for anyone who gets “taken” on a cruise ship. I do a lot of appraisals and I’ve come across a number of instances of so-called “original art” that was sold on cruises, and I have never yet encountered an original work of art by Picasso that exchanged hands in that venue. The only exception is the case of a reputable dealer with whom I am friendly, who consigned original works to a cruise auctioneer. The problem there was that he got back neither the prints nor the proceeds.

Unfortunately, not all ruses are obvious. One may need to examine the actual print first hand to discern whether the paper type is correct and whether the proper watermark is present. The handwriting and the medium of the signature and other inscriptions may also offer clues. However, on otherwise good prints, there are some forged Picasso signatures which even fool the experts. Picasso had better things to do than sign prints all day, and some editions of his prints are less signed than others. Yet, in the wrong hands, the temptation to forge his signature must be great, because it more or less doubles the value of the print if done well. I know of two successful dealers of whom it has been said by reliable sources that they can sign his name in the dark! Fortunately, in almost all of Picasso’s prints, with the notable exception of the prized Vollard Suite, each print edition is known to have been either signed or not signed. Therefore, the temptation to forge his signature on a print that is not supposed to be signed is presumably small, since no informed person would be fooled.

The lengths to which these criminals go to convince the unwary are impressive. For example, I recently uncovered a cache of twenty some-odd Picasso drawings accompanied by letters of authentication from Maya Picasso, Paloma Picasso, and the former collector and dealer, Douglas Cooper, from whom they purportedly devolved in a chain of fictitious provenance to the current owner. Sounds nice, except for the fact that each of these letters was a forgery.

One of the more difficult forms of forgery for the novice to detect is called heliogravure, or photogravure, and is defined as a ”commercial photo-etching, an intaglio form of printing capable of very fine tonal gradation without the use of a halftone screen”. Simple photoreproductions will display a dot matrix when inspected through a jeweler’s loupe, but not these. The reason is that this is a sort of hybrid technology involving photography of the original image and then etching onto a copper plate so that the paper actually feels a bit rough because of the slightly raised surface where ink has been applied. This you of course you wouldn’t feel with a simple photoreproduction. Thankfully, there are a number of ways to detect these forgeries, not only because the forgers almost always slip up. But even if they didn’t, these prints still look very different than the originals from which they were copied to the expert eye. Three of these heliogravures with forged signatures that were passed off as originals and which I’ve recently reviewed are Bloch numbers 1484, 1510, and 1512, but there are many more. Needless to say, despite their similarity to the real thing, these fakes are just as worthless as any other less convincing fakes; they’re just more difficult to spot to the untutored eye.

More examples abound, but I’ll stop here in the interest of space. Now that you know it’s scary out there, whom do you trust? The biggest auction houses, notwithstanding that they have been found to collude in price-fixing, are quite honest and knowledgeable in describing their lots. Curators are also an excellent source. Dealers, on the other hand, may perceive a conflict of interest in evaluating works obtained from their competitors. But the bottom line is and should be caveat emptor, buyer beware. As I often told my patients, trusting a professional blindly is a poor substitute for educating oneself.

The best thing to do when encountering heliogravures or other fakes, at least when attempts are made to pass them off as original prints, is to report their existence and their source to several concerned entities, including but not necessarily limited to the following:

1. The FBI, which is already investigating this kind of fake of the 347 and 156 Series and of The Vollard Suite,

2. The International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR, http://www.ifar.org/).

IFAR’s website states the following about its fees, “IFAR charges an initial, non-refundable $250 deposit at the inquiry stage. This will be applied to the basic $2,000 cost if IFAR is able to undertake the research and the client and IFAR agree to proceed. Additional charges may be required for technical analysis or other work; however, this would not be undertaken without the owner’s consent.”

Part C: OVERPAYING

Fraud is one thing, but one must also avoid overpaying. It is not fraudulent to overcharge, but it is of course unwise to overpay. The problem is that prices vary dramatically in the original print world, both among auctions and dealers. Given lots may be overbid in an auction because of two enthusiastic collectors who are unaware of the actual market value of the object of their fancy. Among art dealers, who are naturally fully aware of the market value of their pieces, price nonetheless varies dramatically. The difference is often related to the dealer’s overhead and their target market. If a dealer has a large staff and pays a high rent for gallery space in the center of a tourist district in order to lure unsophisticated vacationers into his lair, then his mark-up is often as much as five- or ten-fold.

The world-wise gallerist employs a number of artifices to achieve astronomical prices. The scenario goes like this: Something catches your eye through the window, you unsuspectingly enter the art gallery, and, VOOOOOOM, one or more gallerists or their salespeople immediately descend upon you. Their repartee is excellent, all the more if enhanced by a Commonwealth or French accent. All you do is just hint at an interest in a particular work of art, and off it comes from the wall and into the “closing room”, with you in tow. It is hung in the most prominent spot in this room, with ideal lighting. As if that’s not enough, the salesperson then begins playing with the rheostat to simulate the appearance of the piece at various times of the day in your home. All this to the incessant accompaniment of the salesperson’s spiel about the seminal work of art to which you have taken a fancy, its beauty, its significance, and its rarity. Please, do yourself a favor and take all of this with a grain of salt. Make that a boulder of salt.

The opposite extreme is the private dealer, with comparatively minimal overhead and no impulse buyers, who as a result must often (but not always) settle for a mark-up as little as 5 or 10%. Private dealers generally cater to more sophisticated collectors who know what they’re looking for and appreciate a fine print, as well as a good deal, when they’ve found it.

Beware of overpaying. There are many successful art dealers who are completely scrupulous, sell only original works of art, but nonetheless vastly overcharge. For example, there was an art dealer in Manhattan who was gifted with a wonderful personality and whose gallery functioned as a latter-day salon. Collectors loved to congregate there and enjoy the dealer’s fascinating dialogue. They bought a lot of art from him, often never realizing that they vastly overpaid until many years later, when they decided to sell. Imagine their surprise upon learning that, despite the passage of time, the market had not yet caught up with the inflated prices they had paid. For buyers, there is no escaping the need for due diligence prior to purchase.

Picasso’s works set record prices from early on in his career, and they continue to do so. If any art appreciates in the future, Picassos will, too. Nonetheless, it goes without saying that your goal should be to buy at the right price at the time of purchase.

In this context, you may have surmised that buying from an art dealer is bound to be more expensive than buying at auction, because, at auction, you’d be paying the same prices as the art dealer against whom you’d be bidding. It’s worth noting, however, that this assumption is not entirely true. Auctions do in fact function as the great leveler, as well as the location where market prices are established. But they are not the only place where art dealers pick up inventory. Dealers buy from other dealers, and, especially if they’ve been in business for a while, they also encounter opportunities to buy work back from their clients. A dealer can buy for less from clients who want to sell back than at auction, since the auction house takes over a 30% bite. Thus, depending on the dealer’s price structure, which in turn is related to his overhead and his market strategy, the dealer may be able to offer works for sale at even less than the prevailing auction prices. That’s not generally the case, but the careful comparison shopper will seek out those dealers where this does apply.

It is true that collectors can often find the best prices at auction. But there are times when a bidding frenzies can quickly spiral the hammer prices into the stratosphere. This happens with selected lots at a given auction, and it happens at times with an entire auction. It’s not the dealers who are responsible, because they know at what prices they can profitably resell the items, and those beyond which they are better advised to keep their hands on their laps. Not necessarily so with non-professional bidders, who may not know the market value of a given piece, or who may not care. A private collector is much more likely than a dealer to become so enamored of a work of art that he is willing to pay any price. All it takes is two such collectors, and the price goes sky-high. Unfortunately for everyone but the auction house and the consignor, one sees this happening time and again. Dealers’ eyes start rolling when collectors bid the price up so high, knowing that multiple dealers in that very room could offer these crazed bidders the same work for much less than they are preparing to pay.

Then of course there’s buyer’s remorse. What happens once you learn that you overpaid? Or if your taste changes after purchasing the art? Does it help to sleep over it? To see it framed? Above your red sofa? How permanent is your first impression, when you first see the art? Will it vary over a week, a month, or a year? If the piece takes your breath away, will that feeling ever go away? The prospect of buyer’s remorse is yet another reason to buy from an art dealer. Whereas every purchase at auction is irrevocable, most art dealers are willing to let you take the piece home with you, hang it over your red couch, and live with it for a while. Terms vary, and the variations are not insignificant. Although not as important as finding the right piece for the right price, hunting around for the best terms helps to insure the ideal remedy in the event that you change your mind.

Well, that’s it for now. You’re on your own! I would appreciate your feedback, however, in efforts to improve this manuscript for future readers. In the meantime, I hope that you will build a nice collection for you and yours, and that you enjoy the hunt! Before signing off, however, I’d like to leave you with the following words.

I don’t know about you, but my decision-making process when choosing whether to buy a particular work of art basically comes down to this. For whatever reason a work has piqued my interest, and once other essential criteria have been satisfied such as condition and price, there eventually comes a time of reckoning, a moment of truth, when I stand in front of the work at length, with utter focus, and without interruption. As the work is usually a human or animal portrait, a staring contest ensues between us. My thoughts during this battle of wits are always the same: How does the work move me? Why, and to what extent, does it move me? Is the work riveting? How engaging is its subject? Has the artist succeeded in laying bare her soul? Does her personality shine through? Do I sense that I now know her? Has the artist really managed to convey the feeling he had in mind—be it sadness or joy, levity or gravity—or, since that is to some degree unknowable, has he at least managed to elicit an intensity of feeling in my mind to the fullest extent possible? How profound is this feeling, and how long is it likely to last—for an hour, for a day, or for a lifetime? If I blink first, if I avert my gaze unsatisfied, I walk. If she blinks first, I buy.