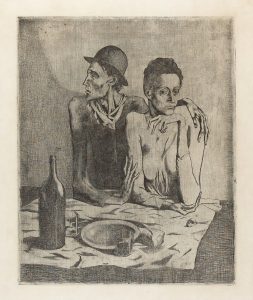

Picasso’s first print was a masterpiece, provided that one doesn’t split hairs about which print in fact came first. Apart from one inconsequential and exceedingly rare if not unique etching of 1899 (three impressions may have been printed, but the existence of but one is known today), Picasso began printmaking in earnest in 1904 with a series of fifteen etchings and drypoints known as La Suite des Saltimbanques (The Saltimbanque Suite). The first of these was Le Repas Frugal (Fig. 1, Georges Bloch Catalogue Vol. 1, number 1), widely considered one of his very best prints, a testament to a genius who could master a new medium so readily and so completely as to emerge at its pinnacle by the time he had completed a single work. The art dealer Ambroise Vollard published it along with the fourteen smaller prints in an unsigned edition of 250 plus an edition of 27 or 29 on Japan paper. These are all the prints which correspond to his Blue and Rose Periods, both temporally and stylistically, if not in coloration (they are all printed in black, apart at least one pre-steelfacing impression of Le Repas Frugal that was gratifyingly printed in blue) and are therefore among the only Picasso prints that would strike the fancy of the typical Picasso hater, like my dear, departed mother, who only liked the Blue Period.

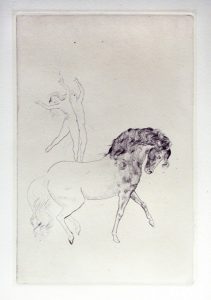

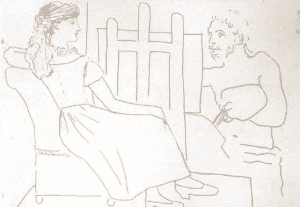

au Profil (Bloch 6)

Brigitte Léal, et al. provides the historical context of Le Repas Frugal in The Ultimate Picasso, p. 72: “Picasso returned to Paris in April 1904, accompanied by Sebastia Junyer Vidal. In the heart of Montmartre, Picasso took one of the studios in the house at 13, rue Ravignan, known as the Bateau-Lavoir. His neighbor, Fernande Olivier, who would be his lover and companion until 1912, remembered ‘a mattress on four legs in one corner. A little iron stove, covered in rust; on top a yellow earthenware bowl for washing …. A cane chair, easels, canvases of every size and tubes of paint scattered all over the floor with brushes, oil cans, and a bowl for etching fluid …. At the time, Picasso was working on an etching, which has since become famous, of a man and a woman sitting at a table in a wine shop. There is the most intense feeling of poverty, alcoholism, and a startling realism in the figures of this wretched, starving couple.’ The etching was The Frugal Repast…and it set the tone for his new style, which adopted a mannerist technique emphasized by means of a sharp, rather nervous line.”

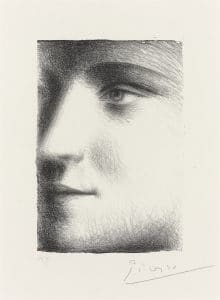

Interestingly, our contemporaneous drawing, Femme de Profil, apparently a preparatory drawing for Le Repas Frugal at least in regard to the woman’s raised hand, reveals how Picasso first elaborated the complex attitude of this hand. It is less clear whether his lover Madeleine, the subject of this drawing, was also the model for the woman’s face in Le Repas Frugal. Tête de Femme au Profil (Fig. 2, Bloch 6) is however undoubtedly a portrait of Madeleine, as its subject sports his lover’s identifying forelock.

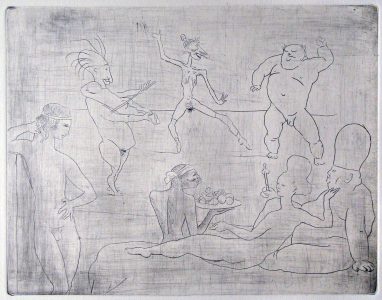

Saltimbanque refers to the street circus performers who had wandered through Europe from the Middle Ages and whom Picasso encountered at the turn-of-the-century Paris, despite the fact that some of the prints in the series are portraits having nothing to do with the circus. In addition to Le Repas Frugal, the two next most sought-after are busts of Madeleine, one of Picasso’s consorts at the time (Bloch 2 and 6—her profile in Bloch 6, Fig. 2, is more desirable than the frontal view of Bloch 2). In general, the etchings that comprise the Suite are charming in that classically Blue and Rose Period sort of way: not necessarily with its famously elongated line (a number of the figures are frankly rather squat), but with that certain nobility amid poverty and sadness that we’ve seen in the paintings of this period (Figs. 3-5: Bloch 7, 9, and 10).

au Repos (Bloch 10)

Much has been written about the importance of the circus in Picasso’s youth. The circus and the bullfight were the two salient cultural elements of his background. Well beyond mere pastimes, both assumed great symbolic significance in his life. The demi-monde of the circus, with its inherent earthiness and physicality, represented an utter abandonment of the bourgeois career path, never a realistic option for Picasso. To some extent, inspired perhaps equally by acrobat and matador, Picasso saw himself not only as an explorer but also as an entertainer. Always the ringleader, he was also the clown of his coterie of friends. We also know that he delighted in impressing his friends artistically from an early age with his uncanny party trick of drawing a portrait upside-down while sitting opposite its subject so that, as the drawing unfolded, it would appear right-side-up to his inevitably amused subject.

Table Legend:

Rarity: * = 200-300, ** = 110-199, *** = 50-109, **** = 25-49, ***** < 25.

Size (in cm): * < 21, ** = 21-34, *** = 35-40, **** = 41-60, ***** > 60.

Cost: You may be interested in the absolute values, and not just the relative values, of the cost of the prints. Clearly the absolute costs vary in time much more than their relative costs, but it may be somewhat useful for you to know how I approached the relative valuations. The relative costs are based on auction prices as recent as 2004, and generally focused on those prints which were in reportedly very nice condition. Though many 2005 prices were available at the time of this writing, I did not incorporate them in order to provide an accurate snapshot at a point in time. A small amount of newer data would have skewed the scale of all the rest of the data points. For source data, the auction record was much more useful than the record of art dealers’ sales, as I’ve described elsewhere, for two reasons. The auction record is more complete and more accurate, and prices realized at auction vary much less than those charged by gallerists and private dealers. To predict a dealer’s prices from these data is difficult, since dealers mark-ups seem to range from less than 10% to more than a 1000%. But you can use the data to give you a relative idea of the prices that Picasso’s prints fetch at whatever venue. In any event, here’s the legend: * < $10,000 (often much less than $10,000), ** = $10,000 to 20,000, *** = $20,000 to 50,000, **** = $50,000 to 100,000, and ***** > $100,000 (usually not much more than$100,000, though the occasional auction price has already exeeded a million dollars).

Signature: Y (yes, signifying that most of the impressions were signed, and that the signatures were by Picasso’s own hand), ES (Estate Stamped, with a stamp reproducing one of Picasso’s signatures), Y/N (maybe, meaning a fair proportion were signed), P (signed in the plate or on the stone), and N (no, signifying that most of the impressions were not signed).

Table 1. Les Saltimbanques Suite

| Bloch # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Beauty | ***** | **** | ** | *** | *** | **** | **** | **** | *** | **** |

| Significance | ***** | *** | ** | *** | *** | **** | *** | *** | ** | **** |

| Rarity | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Size | **** | * | ** | * | * | ** | ** | * | ** | * |

| Visibility at a distance | *** | *** | ** | *** | ** | *** | * | * | * | * |

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | ***** | ** | ** | * | * | ** | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | *** | ** | ** | **** | |||||

| Signature | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

Table 1. Les Saltimbanques Suite, Cont.

| Bloch # | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Beauty | **** | * | ** | * |

| Significance | **** | * | ** | * |

| Rarity | * | * | * | * |

| Size | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | * | * |

| Color | ||||

| Fading | ||||

| Cost | ** | ** | ** | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | |||

| Signature | N | N | N | N |

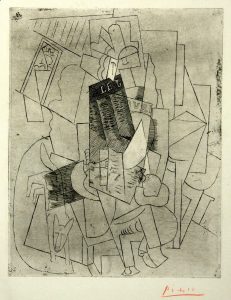

Those of you who crave Cubism have a few lovely, mostly small prints to choose between (Table 2). The masterpiece print of his Cubist period is considered to be the Still Life with Bottle of Marc (500 x 305 mm.; 19.7 x 12 in.) of July, 1911 (Bloch 24). I don’t at all think it’s his masterpiece, in any sense other than size. For beauty and style, I prefer a number of others, particularly Bloch numbers 19, 28 (Figures 7 and 8), and 30. The first of these is notable for its light, sprightly, flowing, charming, dancing, recognizable, movement and form and its wonderful and hilarious geometric component parts. The other two are remarkable for their complexity and B30 in particular for its atmospheric subtlety. (Note: you may need a larger photo than Bloch affords to even begin to appreciate Bloch 30.)

Léonie (Bloch 19)

au Chien (Bloch 28)

Table 2. Cubism (1909-1917)

| Bloch # | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| Beauty | * | * | **** | * | ** | ** | * | * | ** | ** |

| Significance | *** | *** | **** | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** |

| Rarity | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Size | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | **** | * | * |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * |

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | *** | ** | *** | *** | ** | ** | *** | **** | ** | ** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N

|

Table 2. Cubism (1909-1917), cont.

| Bloch # | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 |

| Beauty | ** | *** | * | **** | ** | ** |

| Significance | *** | **** | *** | **** | **** | **** |

| Rarity | ** | *** | ** | **** | **** | |

| Size | * | ** | * | * | * | * |

| Visibility at a distance | * | ** | * | * | * | |

| Color | ||||||

| Fading | ||||||

| Cost | ** | *** | * | *** | ** | ? |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | |||||

| Signature | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

Picasso made precious few prints during his first four decades. He slowly increased his output in the 1920’s, when turning to his neoclassical style. Sadly, a number of the wonderful styles he created in the ‘twenties in his drawings and paintings, such as his sculptural paintings, are hardly represented in his prints.

Table 3A. 1918-1923: mostly naturalism and neo-classicist styles

| Bloch # | 33 | 34 | 37 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 49 | 51 |

| Beauty | *** | *** | **** | * | ** | * | * | *** | |

| Significance | ** | ** | *** | * | ** | ** | * | ** | |

| Rarity | ***** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | **** | *** | ** |

| Size | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | * |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | ** | * | * | * | |||

| Color | |||||||||

| Fading | |||||||||

| Cost | *** | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | ** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | ||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | ES | Y | Y | N | N | ES | Y

|

Table 3B. 1918-1923: mostly naturalism and neo-classicist styles, cont.

| Bloch # | 52 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 |

| Beauty | * | * | ** | *** | * | *** | ** | * | ** | ** |

| Significance | * | ** | ** | * | ** | ** | * | * | * | |

| Rarity | **** | *** | *** | ** | *** | ** | *** | *** | ** | **** |

| Size | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | * |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | ** | *** | * | ** | ** | * | ** | ** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||||||||||

| Signature | ES | ES | Y | Y | ES | Y | Y | ES | Y | N |

Table 4A. 1923-1927: mostly naturalism and neo-classicist styles

| Bloch # | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 72 | 73 | 74 |

| Beauty | ** | * | ** | * | * | * | * | *** | * | |

| Significance | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | *** | ** | |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** |

| Size | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | **** | * | * | ** | |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * | ** | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ES | Y | Y |

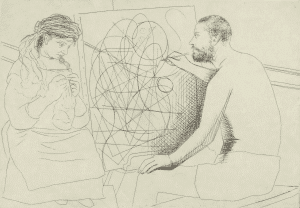

Among the earliest expressions in Picasso’s printmaking of his neoclassical style is the beautiful etching, Le Modèle Habillé (The Clothed Model) (Fig 9, Bloch 79). The painter and the model in this studio scene have an equal measure of poise and presence. What’s amusing about this rather rare piece is its title. By indicating that the model is clothed, the title serves as an unnecessary reminder that the default state of the model in Picasso’s oeuvre is, of course, in the nude! Unless specifically qualified that the model is dressed, one has reason, based on even a glancing familiarity with Picasso’s work, to assume the opposite….

The artist and his model was a recurrent, signature theme spanning many decades of Picasso’s life. The sculptor’s studio, to give but one example, was the dominant subject of The Vollard Suite, the 100 prints of the early ‘thirties which constitute Picasso’s most celebrated print series. The group of three etchings to which this lovely print belongs is however noteworthy as the very first time Picasso introduced the theme of the artist’s studio to his printmaking.

Table 4B. 1923-1927: mostly naturalism and neo-classicist styles, cont.

| Bloch # | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 |

| Beauty | * | * | *** | ** | * | ** |

| Significance | * | ** | * | *** | ||

| Rarity | ** | * | ** | *** | ** | *** |

| Size | **** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | ||||||

| Color | ||||||

| Fading | ||||||

| Cost | ** | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | ** | ||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y

|

In 1931, Picasso created a series of book illustrations for a deluxe edition of Balzac’s short story, Le Chef d’Oeuvre Inconnu (The Unknown Masterpiece, Table 5). See the discussion of this book and the etching below (Bloch 85, Fig. 8) on its webpage in our sales catalogue.

Tricotant (Bloch 85)

Table 5A. Le Chef D’Oeuvre Inconnu, 1927

| Bloch # | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 91 |

| Beauty | * | *** | *** | * | ** | * | ** | * | * | |

| Significance | * | * | *** | *** | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Rarity | ||||||||||

| Size | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | ||||||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | *** | ||||||||

| Signature | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N |

Table 5B. Le Chef D’Oeuvre Inconnu, 1927, cont.

| Bloch # | 92 | 93 | 94 |

| Beauty | |||

| Significance | * | * | |

| Rarity | |||

| Size | ** | ** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | |||

| Color | |||

| Fading | |||

| Cost | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | |||

| Signature | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N |

Table 6 lists four miscellaneous prints including a wonderful, realistic, but very close-up profile of Picasso’s new mistress, Marie-Thérèse (Bloch 95, Fig. 11).

Table 6. Four miscellaneous prints, 1928-1930

| Bloch # | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 |

| Beauty | *** | ** | * | |

| Significance | *** | ** | ||

| Rarity | *** | ** | ||

| Size | * | ** | ** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | ||

| Color | ||||

| Fading | ||||

| Cost | ***/* | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | _/* | |||

| Signature | Y/N | N | N | Y

|

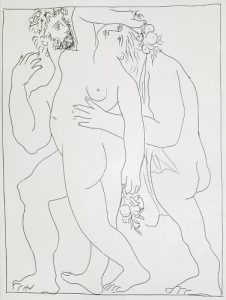

Picasso inaugurated the next decade, a most portentous one for his oeuvre, by famously illustrating Ovid’sMetamorphoses (Table 7; Fig. 10, Vertumne Poursuit Pomone de son Amour [Bloch 126, 1930, see also a discussion of this etching in our catalogue]; for Bloch 125, refer to Chapter 1, Fig. 12).

de son Amour (B126)

There could be no better fit between text and illustrator than a story of transformation, the very hallmark of Picasso’s art. The thirty wonderful and deceptively simple portraits that comprise this series include fifteen half-length portraits which illustrated the chapter titles and bore no specific relationship to the text. The full-length works did however closely correspond to the narrative, which was unusual in Picasso’s illustrated books. This series was created contemporaneously with the earliest prints of The Vollard Suite, with which it shares the simple elegance of the artist’s neoclassical style.

Albert Skira was just starting out in the publishing business when he decided to shoot for the stars and ask Picasso to illustrate a book for him. Picasso agreed but was at a loss as to which book to choose to illustrate. After some time, Picasso related a dream to Pierre Matisse, the artist’s son, in which women were transformed into fish. Pierre seminally proposed that Picasso illustrate Ovid’s Metamorphoses. For his fiftieth birthday on October 25, 1931, Picasso received the first proof of this book from Skira.

Table 7. Ovid’s Metamorphoses, 1930-31

| Bloch # | 99 | 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | 107 | 112 | 113 | 125 | 126 |

| Beauty | *** | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * | *** | **** |

| Significance | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | **** | **** |

| Rarity | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Size | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | ||||||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | * | *** | **** | ||||||

| Signature | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |