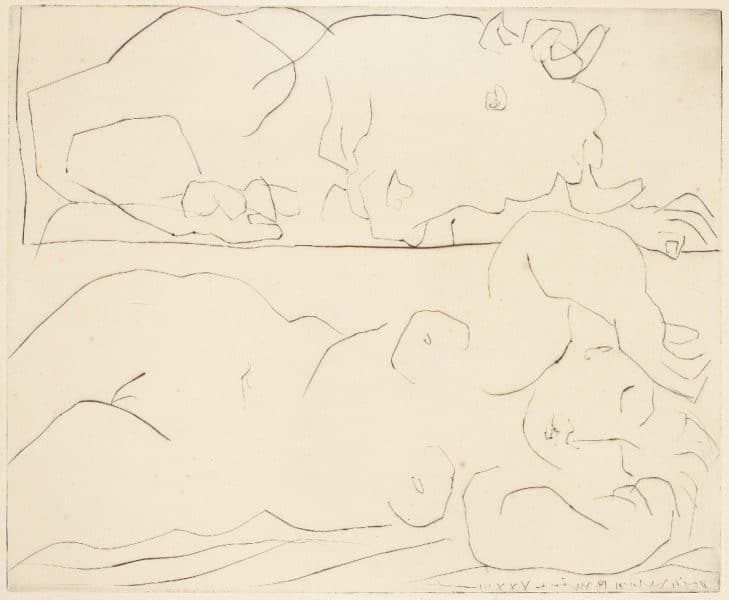

Minotaur Lovingly Regarding a Sleeping Woman

Date: June 18, 1933

Medium: Drypoint on copper with plate tone and black ink without steelfacing

Dimensions: Print 298 x 364mm, 11 3/4 x 14 3/8″; Sheet 412 x 520mm, 16 1/4 x 20 1/2″

Signature: Picasso did not sign the edition, though most impressions, unlike this proof, bear his estate-stamped signature.

References: Bloch 261; Baer 371 Bb2

Edition: RARE–one of three unsigned and unnumbered proofs printed in 1961 (aside from the edition of 20 numbered proofs and 12 artist’s proofs also printed in 1961, and 4 trial proofs the year before), published by Galerie Louise Leiris prior to the cancellation of the plate in 1979

Paper: Van Gelder laid, untrimmed

Impression: Very fine, especially because the edition was printed without steelfacing

Condition: Pale toning of the image and central margins due to exposure to sunlight, which creates a lovely cream color; several scattered, pale foxmarks; scattered thumbnail-shaped soft handling creases, most notable in the left margin; mild undulation of the sheet in the upper and lower margins; remnants of tape from previous hinging at intervals along all four edges of sheet, verso; all in all, in very good condition; framed

Price: Upon request

Picasso created four intaglio prints on June 18, 1933, all of which dealt with the theme of the Minotaur. Apart from the first one, Minotaure, Buveur et Femmes (Minotaur, Drinker, and Women; Bloch 200, Baer 368), the remaining three tell a story in three frames. Although Picasso didn’t number them, he must have clued Brigitte Baer in, who then in her catalogue numbered them in the order of their creation, which order quite naturally corresponded to the progression of the story. (This is not the only time during this period of the artist’s work in which she made such catalogue annotations, but it is the only series of prints of which I’m aware which tell a coherent story.) As usual, Baer’s titles are more descriptive and informative than those of Georges Bloch. The first “frame” of this story is this drypoint, which she named Minotaure Contemplant Amoureusement une Dormeuse, in which the Minotaur Amorously Contemplates a Sleeping Woman through on open window. The Minotaur has entered the bedroom by the next frame, which Baer titles Minotaure Caressant du Mufle la Main d’Une Dormeuse (Minotaur Nuzzles the Hand of the Sleeping Woman; Bloch 201, Baer 369) and thereby explains the action which, at least to this viewer, is not completely clear in the print itself, and which Bloch’s shorter title didn’t elucidate. The final frame, Minotaure et Femme Faisant l’Amour (Bloch 262, Baer 372) shows the couple making love, not exactly a surprise ending. (Bloch, as he often does, titles this final scene as a rape, but Baer’s lighter touch is probably also more accurate, as she was much more intimately involved with Picasso’s printmaking.)

Apart from the fourth and final print of the day, which was not very well realized, the other three Picasso created that day are all masterpieces. In my opinion, the drypoint at hand is lovelier than Bloch 201, and it is also ten times as rare. (Although steelfacing hardens the incisions on the plate, thus permitting a larger edition without degradation of the lines through repetitive printing, the steelfacing itself degrades the line’s boldness and burr. Picasso’s choice to avoid steelfacing this drypoint therefore determined its small edition size.) Yet this artwork sells for an order of magnitude less than Bloch 201. Such are the vagaries of the marketplace, in this case partly explained by the imprimatur of the Vollard Suite which the latter bears, as well as by the desirability of Picasso’s autograph. Another likely reason is the spare line of this drypoint, in contrast to the more overworked second frame, as the market tends to value art, at least to some extent, in proportion to its detail. For the artist, the art is a realization of his vision, but for us, the admirers of his art, it is all just a matter of taste.

Personally, although I admire the fine details of Picasso’s art as much as the next art lover, I value Picasso’s economy of line just as much. In this wondrous creation, there is hardly an unnecessary detail. To me, the greatness of this artwork, apart from its sheer beauty, is largely due to the precious few strokes of the drypoint with which the master evoked the Minotaur’s emotion, whether love or lust, and the peaceful repose of the object of his desire. Amazingly, Picasso achieved the beast’s tender expression with but two lines.

The first print of the day was an etching, Picasso’s most frequently used printmaking technique by far. Perhaps because of the spare line of this next print, Picasso then took up his drypoint and, when it came time to print the edition, he did so without steelfacing, thereby preserving the burr of the drypoint’s incisions and heightening the boldness of its lines.