Now that everyone else has opined about the last auction round, having waited my turn, I can now get in the last word. The art world seems rather pleased with itself in view of the continued price escalation, with no end in sight. Yet the intelligence of the market is still underappreciated. It’s time, it seems to me, that buyers be given their due. And of course I’m just talking about buyers of Picassos, since those are the only works I study in depth. Commentary about the intelligence of the art market in general has not been quite so favorable. For example, note the opening line of Souren Melikian’s essay: “The May sales demonstrated how unpredictable buying patterns have become. With the nature of the work now irrelevant, the artist’s name and fame alone matter.” (Art + Auction, July 2007, pp. 41-46) That may be true in general, but the Picasso market seems different. If Picasso was the intellectual’s artist, perhaps his presumably intellectual collectors have a leg up.

The first thing one notices about the Picassos in the spring season is the abundance of great works. At a second glance, the sales were also particularly illustrative of another matter, which I found quite encouraging. Much like real estate, art is all too often valued by the square foot. But, regardless of what my wife may think, size is overrated. Sure, décor matters, and a miniature will not command a large space. But a vibrant work of art with a bold design capable of resolution from across the room will “hold the wall”, even if it’s small. The Picasso market, which seems to be getting smarter all the time, is finally coming around to this realization. Just look at the Picasso paintings of but one recent auction, Sotheby’s NY Evening Sale, May 8, 2007:

1. Tête d’arlequin, 1905, lot 18, oil on panel, 35 cm (13 ¾”), a wonderful rose period portrait, sold for $15,160,000 (with premium).

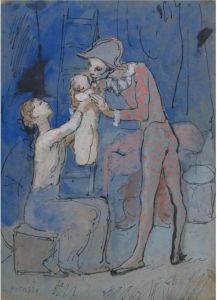

2. Famille d’arlequin, 1905, lot 21, gouache and ink on card, 29.5 cm (11 5/8”) sold for $9,840,000.

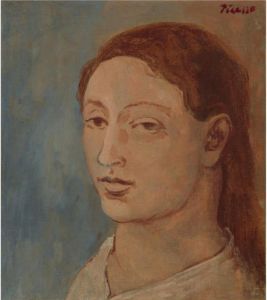

3. Tête de fernande, 1906, lot 24, an oil and gouache on canvas, 37.5 cm (14 ¾”), sold for $6,760,000.

4. Homme à la pipe assis dans un fauteuil, 1916, 32 cm (12 5/8”), an oil and gouache on paper laid down on canvas, sold for $4,744,000.

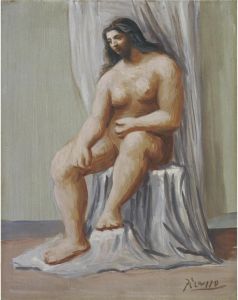

5. Femme nue, assise contre une draperie, 1922, 24 cm (9 ½”), lot 17 a sculptural woman in oil on panel, sold for $2,392,000.

The only absurdity in these sales, as far as I’m concerned, is number 2 above, which admittedly featured an iconic early Picasso theme and, though colorful and well designed, was poorly drawn, being rather sketchy. It goes to show that the Picasso market, in my opinion, still has a thing or two to learn. In this case, that color isn’t everything. Sure, color matters, but certainly not at the expense of design and graphic quality.

Interestingly, Melikian’s opinion was that the Picassos were relative bargains:

“Throughout the session, money was spent without much discrimination between the great and the merely good. The most astonishing example of this was provided by the contrasting prices fetched within 10 minutes by one of Picasso’s greatest early works and an interesting but forgettable street scene by Lyonel Feininger.

“Picasso’s Tête d’Arlequin, painted in 1905 [number 1 above], ranks among the last major masterpieces of European psychological portraiture. Here the Paris school artist translates the lessons he assimilated from the Old Masters into the idiom of modern art. Although the brushwork is broad, giving precedence to light and shadow over details, the psychological probing is as profound as in any work from past centuries. The estimate, $14 million to $18 million, was steep but not mad for a picture bound to end up someday in one of the world’s leading museums. However, the Picasso did not even match the lower end of its estimate, selling for $13.5 million plus the $1.7 million premium. Whoever won the bidding contest made the cleverest buy of the week.

“Now consider the very different fate of the Feininger, four lots down. Jesuiten III (Jesuits III), painted in 1915, lacks the punch of this artist’s best work. It is little more than a genre scene in a Mannerist style that is unusual for its author. [Mannerist? Maybe, but it also looks like a somewhat derivative, quasi-cubist riff to me.] This did not stop it from establishing a record for the artist, at $23.3 million. The ratio between the prices for the Feininger and the Picasso should have been 1 to 4. Instead, it was roughly 1.5 to 1.”

It didn’t hurt the Feininger’s sale, of course, that it was featured on the front cover of the auction catalogue. Notice, however, to Melikian’s credit, that he didn’t mention the vastly different sizes of these two works. The Feininger measured 75 x 60 cm, contrasting with the Picasso’s 35 x 26.5 cm. In so doing, he seems to have echoed the wisdom of the Picasso market today: size doesn’t matter, at least by comparison to the overall beauty of the art and its importance in the artist’s oeuvre.