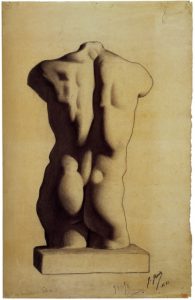

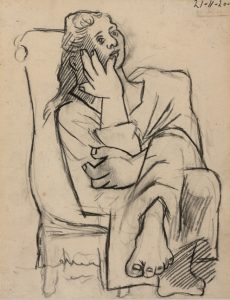

Pablo Picasso was born in Malaga, a small town in southern Spain, in 1881. Or perhaps one should say stillborn, as he indeed seemed to be, until his fast-thinking uncle exhaled cigar smoke into the baby’s face and Pablo sprang to life. It is said that his first word was “piz”, short for “lápiz”, Spanish for pencil. He did in fact begin to draw and paint quite early and rapidly achieved such mastery as to surpass his father, an academic painter, who as a result gave up his brushes and paints while his son was still a child. In Picasso’s words, “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.” Although that was clearly an exaggeration, this is what his art looked like at age 12 and at 14:

1893-4, charcoal and pencil

1896, oil on canvas

Picasso studied art for less than six years and then dropped out of school in favor of making his own way as an artist. He began by interpreting the styles of the Old Masters, always adding his own twist. As he later said, “Good artists borrow, great artists steal.” In 1900 Picasso first visited Paris, the epicenter of the art world at the time, and by 1904 he had permanently emigrated. In Paris he soon became the ringleader of a band of artists and writers, just as he had been in Spain. At first he was destitute and made ends meet by overpainting his canvases. One cold Parisian winter he reputedly burnt his paintings for warmth.

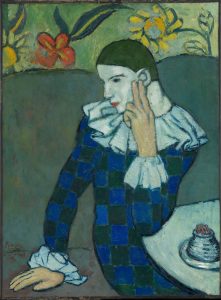

But Picasso did not become Picasso until 1901, when he created his first highly original style, the Blue Period, and landed his first solo art show:

oil on canvas, 1901

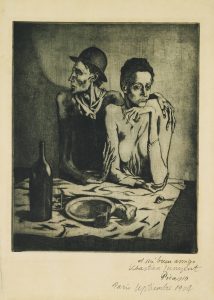

etching on copper, 1904

Picasso’s first great print

If he had stopped then, after this brief, 3-year period, his accomplishments would already have surpassed his contemporaries and equalled the great masters of the past. Instead, he went on to produce countless new styles. And each and every one of his styles became a triumphant success.

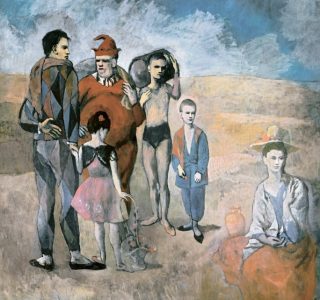

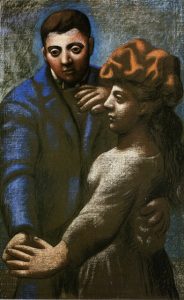

As he moved beyond the pathos and introspection of the Blue Period, Picasso’s palette became warmer and gave rise to the even shorter Rose Period. Though still rooted in the demimonde, the Rose Period depicted a happier side of life, with harlequins and acrobats cavorting in paintings of astonishing beauty:

oil on canvas, 1905

oil on canvas, 1905

During the Rose Period, Picasso further elaborated what was to become a lifelong undercurrent in his painting, its ability to transcend time and place, and to imbue its subject, however mundane, with a timeless universality. He did so in part by stripping his subject of identifying detail and replacing it with nostalgic depictions of a more perfect, idyllic, mythical world.

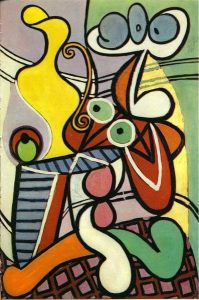

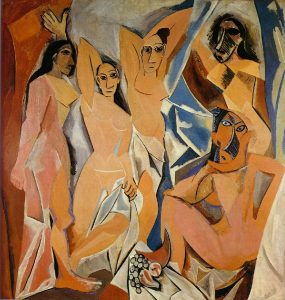

From there, Picasso continued to create new styles with dizzying speed. The most radical transformation of his art began in 1906-07, when he created some 600 artworks leading up to his most important painting–and the most important artwork of the century, The Women of Avignon. If Modern Art could be said to have begun with a single painting, this would be the one:

oil on canvas, 1907

This African or proto-Cubist Period soon morphed into Analytic Cubism, the only original style that he developed in close collaboration with another artist, his friend Georges Braque. Cubism was at first widely derided, before it became their most famous style. It was thusly named by one of its detractors for the myriad of tiny “cubes” with which these artists seemingly composed their subjects:

etching & drypoint, 1910

oil on canvas, 1911

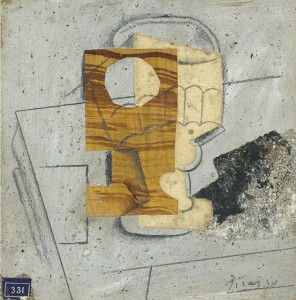

Along the way, Braque and Picasso varied their technique, developing collages which for the first time in history included diverse elements such as newspaper, wallpaper, and found objects, as in this example of papier collés (pasted paper). Note the painted faux wood:

oil, sand, pasted papers

& pencil on cardboard

Whereas Braque’s work diminished after their collaboration ended, Picasso was just beginning. In Picasso’s hands, Cubism now entered its final phase, Synthetic Cubism:

gouache on cardboard, 1920

gouache on paper, 1920

The distinction between Analytic and Synthetic Cubism, to the extent one can tease them apart, is that Picasso divided subjects into innumerable geometric facets in the former and assembled them out of simple geometric shapes in the latter.

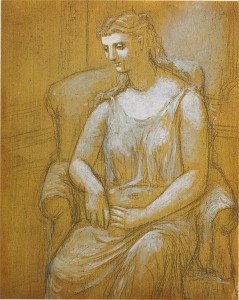

While still working in the Synthetic Cubist style, Picasso created his Neoclassical style during the First World War and turned increasingly to it after the war ended, at times more faithful to its Greco-Roman precedents:

pencil & white oil on wood, 1923

and at other times less so, as he took it through various twists and turns such as his colossal, sculptural paintings and drawings:

oil on canvas, 1921

conté crayon on paper, 1920

For a decade or so (and later also after World War II), he returned to the idyllic world of his imagination, a sharp contrast to the horrors of war:

pen, ink & gouache on paper, 1933

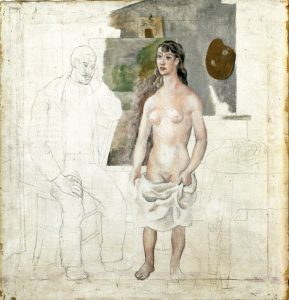

Often he interwove these disparate and seemingly mutually exclusive styles in the same works to startling effect. Remarkably, he worked in multiple styles at once, often on the same day, moving from one canvas to the next, adding a bit to one and then another, before completing any of them. Some works he left deliberately unfinished, and in so doing called attention to the process of creating art:

oil & pencil on linen, 1914

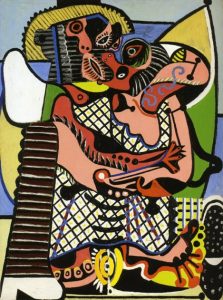

He named the next period, Surrealism, himself, and was at the vanguard of the widespread Surrealist movement that he spawned, despite choosing not to formally associate himself with it. During this period he created some of his most imaginative sculptures, such as these:

plaster, 1931

bronze, 1931

as well as some of his most important paintings:

oil, 1925

oil on canvas, 1931

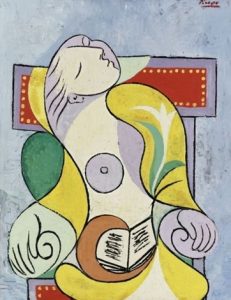

The periods beginning in the ‘twenties are often labeled by their decade, or thereafter by the reigning mistress, starting with Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar, then Françoise Gilot. Picasso’s style changed dramatically with each successive muse, as if each of them imbued him with a different creative spark:

1932, oil on canvas

1932, oil on canvas

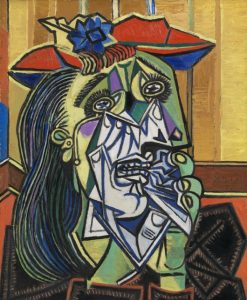

oil on canvas, 1937

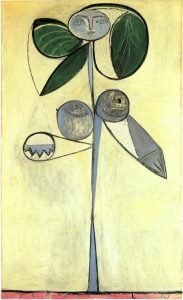

oil on canvas, 1946

World War II broke out during the Dora Maar Period, and Picasso responded with Guernica, the most famous political artwork of all time, and also his largest and most famous canvas, which decried the carpet bombing by the Nazis of that eponymous Basque village in northern Spain. He also created some 200 works related to it, such as these:

oil on canvas, 1937

Horse’s Head

oil on canvas, 1937

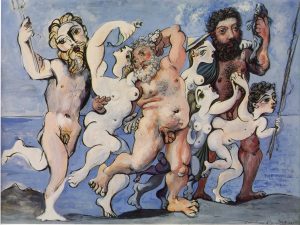

At the war’s end, Picasso permanently relocated to the Mediterranean coast of France, where, as in his previous summers there, his art took on an idyllic quality. Having tired of depicting the horrors of life as it is, he dreamed of life as it could be, while harkening back to a mythical time of fauns and centaurs:

oil on canvas, 1946

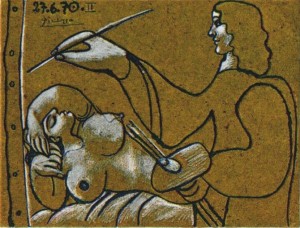

His last two decades were characterized by a stable relationship with the woman who became his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, and his painting consisted primarily of her portraiture, as well as his perennial preoccupation with the subject of the artist and his model, and also many amusing depictions of Spanish musketeers of old:

Pencil & colored crayons on paper

And, as all through his life, Picasso’s love of women infused erotica in so much of his art:

ink and chalk on cardboard, 1970

Each of Picasso’s styles was typically under-appreciated at the time of its creation. As has been said, he was always one period ahead of his audience. Ambroise Vollard, the art dealer who gave him his first solo exhibit, parted ways with him because he failed to understand Cubism, and then struggled to regain Picasso as a client for years thereafter. His dealer in the 1920’s, Léonce Rosenberg, wanted him to paint “prettier pictures”. And it was in the Late Picasso Period (his last 20 years or so) when the artist really left his audience in the dust. Widely ridiculed as the ravings of a demented old man, his musketeers and courtesans required 30 years before they became all the rage.

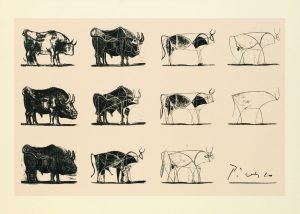

Picasso’s subject matter was diverse, from portraits to animals to still lifes to landscapes, and, famously, his favorite subject was woman. In some cases his subjects were noble to begin with, but more often they were common folk whom he ennobled–and immortalized–with his magic. He also worked in just about every known medium, and he created his own mediums. Just as he had revolutionized art, he also revolutionized the techniques of making art, inventing many during his career. He drew and painted and collaged and sculpted, incorporating all manner of flotsam and jetsam to his art. He sculpted in wood, plaster, metal, and ceramic, and his sculptures were enlarged into massive steel or concrete installations. He made theatre and ballet set designs with stage backdrops and costumes. He created prints on paper, parchment, celluloid, and clay, and invented numerous printing techniques, which secrets he (mostly) took to his grave. He worked tirelessly, usually with many iterations on a theme, remarking in mid-career, “The movement of my thought interests me more than the thought itself.” He may have best captured the movement of his thought in his printmaking, as he often printed one or more impressions at multiple steps along the way to the final state of his print:

on stone), 11 states, 1946

So how do we take the measure this man? How do we define the greatness of an artist? Picasso was a lightning-fast artist who worked tirelessly for over eight decades. He kept at it until 3 weeks before his death, racing against time to express the many ideas still swimming in his head. He created over 25,000 works of art, the most prolific of all artists. He became a billionaire, the wealthiest artist in history. Art historians agree that Picasso was one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century, and many of them conclude that he was the greatest artist of that century. But why mince words? Picasso was the greatest artist of all time.

To defend this thesis, one can begin by pointing to Picasso’s unequaled imagination, as represented in the staggering number of his styles, through which he alternately reflected and distorted reality. Their masterfulness and their complexity (or deceptive simplicity) bear witness to his unparalleled imagination and establish his supremacy. Van Gogh was a great artist, but how many styles did he have? Basically, one. The mature Gauguin? One. Manet? One. Monet? One, one-and-a-half. Matisse? Call it 2 or 3. Miró? Two. The great Renaissance artists? Certainly only one. But in Picasso’s case–too many to count. At times he created a new style every day, His styles overlap, and some show a unique approach to depicting just a part of the artwork, such as individual facial features or the hands or feet, so ultimately it is impossible to make an accurate count. One art historian who tried counting his styles in the early 1950’s came up with more than 80, yet Picasso still had twenty years left in his run.

A second, albeit more subjective argument for Picasso’s supremacy is that his art is beautiful beyond words, in spite of, or perhaps precisely because of its distortions of reality, as opposed to, say, Dali, another great artist, but one whose anatomic distortions were often more grotesque than beautiful.

A third argument for Picasso’s primacy is his graphic mastery (his ability to draw and faithfully represent reality), which was at least as good as any of his predecessors. Certainly no artist has challenged it since.

Picasso reached the top of all three of these pinnacles, a unique accomplishment that defines his greatness. He fundamentally changed the form and composition of painting and sculpture, disrupting the very definition of art. In short, he fairly invented Modern Art itself and applied with unparalleled imagination the concept of “anything goes”, arguably its founding principle.

A Picasso can make us admire and laugh and rage and cry and think. So as you enter deeper into the world that Picasso created, enjoy its wondrous beauty–and prepare yourself for an assault on your eyes, and on your mind.

-Kobi Ledor, M.D.

copyright 2014 to date

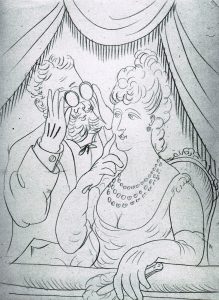

(Study for the set design of

the ballet “Four Flamencos”)

pencil, 1921