In a recent post I argued that Picasso drawings are on a tear. In this one I’ll offer reasons why they are still a buy, especially relative to other Picasso mediums, as well as relative to drawings by other “modern masters”. (Before we begin, in case you’re wondering whether I have any conflict of interest, I should submit that in this case I have no particular disclosures to make except for the general case, which is that we own and offer for sale Picassos in all of these mediums.)

The art market is in a state of perpetual disequilibrium, as we have earlier discussed, and the Picasso market is no exception. But among Picassos, the medium in which the disequilibrium is especially marked are his drawings and other unique works on paper (to which I’ll refer collectively simply as “drawings”). I haven’t done a statistical analysis to support this contention–I’ll leave that to the economists such as Mei and Moses–but my experience strongly suggests that this is the case. The reasons for it, I submit, are pretty straightforward: the relative scarcity of collectors of drawings, and that most of the individual drawings are relatively unknown.

Picasso created more drawings than works in all other mediums combined. It might at first seem paradoxical, then, that his drawings are relatively unknown. Here’s why. His prints by contrast are very well known, at least among print collectors, for a collector has merely to invest in a single book (Bloch, Vol. I) to see the majority of his published prints , including almost all the important ones. The avid Picasso print collector pours through this book repeatedly, commits many to memory, and make lists of his desiderata. (You should see my weathered, 30-year-old copy, or perhaps you have one of your own.) Picasso print collectors are also relatively plentiful, because of course the average original print is at the low end of the art market.

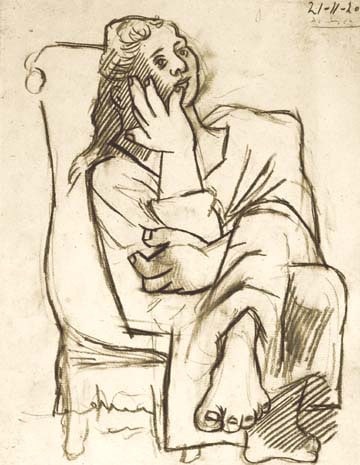

At the other extreme are collectors of paintings and sculptures. These works, despite being at the high end of the market, nonetheless traditionally have attracted more collectors than have drawings. Oils and sculptures stand out more, oils tend to be more colorful, and they are generally considered, by the artists and their fans alike, to be the apogee of the artists’ work. It follows that oils, then, tend to be more widely reproduced in coffee table books than works in other mediums. (For Picasso, typically one would find Le Repas Frugal in many such surveys, but few if any other prints and often not many more drawings.) When an important oil hits the market, it is already well-known and pretty much sells itself, with or without the gallerina’s help. A lesser-known but lovely oil might also fly off the proverbial shelf, if it is colorful and large enough to satisfy the collectors’ criteria. With Picasso, there are so many more drawings than the few that collectors have seen, or remember seeing. There are tens of thousands of Picasso drawings. So many books are required to catalog them (the most up-to-date series is Wofsy’s Picasso Project, which spans 23 volumes and which also includes Picasso’s paintings and sculptures). I suppose most collectors have not purchased them all. When a drawing first hits the market, even a very good one, its value has yet to be established. The gallery’s price tag or the auction’s estimate could be helpful in this regard, but they could just as likely be a hindrance, because of the inherent conflict of interest (you’re buying but they’re selling) and because of the vicissitudes of setting the price (the piece may be worth way more or way less in the seller’s point of view than in yours, the seller may have paid too much, the seller might be desperate to sell, etc.)

Collectors line up when a famous Picasso print is on the block. It is so hotly desired because it is so well-known. An equally great or better drawing by contrast is likely relatively unknown and will often garner much less attention. Don’t forget that some collectors lack taste and are therefore reliant upon their advisors or books. But their advisors may be no more familiar with the drawing at hand, survey books will likely be silent on the matter, and catalogs raisonnés don’t editorialize. Left to their own judgment, many collectors understandably will not part with their hard-earned money on something they’re less sure of.

The ability of the gallery or auction to play up the value of a piece should not be underestimated. The recent $13.5M Picasso Rape that I blogged about is a very good drawing, but could it have achieved anything of the sort without the auction’s hype? Consider the subject matter, let alone the alternatives. I’ve seen many a Picasso drawing every bit as good or better (in my subjective opinion) sell for a tenth of that. Heck, I’ve sold a better work (well, with the auction’s help, that is) for less than a tenth. So now you say, “Sour grapes!” Perhaps. There may be a bit of that. But not much–it’s not me, rather it’s that the chemistry of the art market, and drawings in particular, is in huge disequilibrium. There’s plenty of runaway bidding at one extreme, which you are of course well-advised to avoid unless money means nothing to you. At the other extreme, incredible bargains are quite rare, since Picasso, shall we say, has already been discovered. Today there are still relative bargains aplenty, but they are mostly in Picasso drawings. There are many wonderful drawings that still sell in the 6 figures, and occasionally at the lower end of that spectrum, must-haves, really, if you’ve got the scratch. They may often be underpriced today compared to drawings by, say, Matisse or Schiele, to name but two whose better drawings routinely fetch 7 figures, but that is only because Picasso was so much more prolific (and, presumably, because Germans naturally want to collect their own). But the relative availability of Picasso drawings, I predict, will not last, as more and more disappear into the black holes of museum collections. In time, I expect Picasso drawings to command a few more zeros, not unlike this month’s nearly $50M Rafael. But for now, dear reader, it is the time to buy and hold.