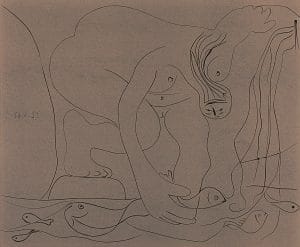

“Color weakens.”—Picasso

Ah, the drab and dreary world of the Picasso print collector. Would it just kill you to throw a splash of color on the wall already, maybe a Chagall or a nice Miro? What is it with you Picasso collectors and your black-and-white prints?

Fair enough. Most Picasso prints are black-and-white. So why collect them? Surely you could fill your house with colorful paintings by unknown, or lesser known, artists for a fraction of their cost. But color alone doesn’t make for good art. The graphic beauty and magnificence of your Picasso prints, just as their value, would last long after the allure, not to mention the value, of your colorful paintings have lost their luster.

Take my wife. I tell her that if she could find any colorful work of art as beautiful as our Picassos, then she is welcome to buy it. Sounds fair, right? Ah, but the devil is in the details. It’s by no means easy to find a colorful painting as wonderful as our Picassos, let alone one with even remotely similar investment potential. (And, yes, we have some colorful paintings by no-name artists in our home, just like you do.)

It goes without saying that, like my wife, if I had to choose between them, I would rather fill my home with colorful Picasso paintings than “colorless” prints. I would choose to collect both if I could, as well as drawings and sculptures, for that matter. But if I could take only prints or paintings with me onto a desert island—no contest—the paintings would win. After all, I’m not a print fanatic. I’m a Picasso fanatic! I love his prints not so much because of his technical accomplishments in that medium (though of course his technical virtuosity is not at all lost on me) as much as because of the beauty of his results. But I’ll be the first to admit that, in general, they don’t hold up to his paintings. Sure, there are exceptions. All in all, however, I’d pack those paintings up for my desert isle, just as you would. But I am fairly confident that your name is not Bill Gates any more than mine is. How are we different from him? We may have far far less money, but we also enjoy far better taste. These distinctions lead us straight down the path to Picasso’s prints.

We color-starved Picasso print lovers really get a rise whenever we see a bit of color in his work. Yet when he finally did throw in some color, all too often it was just a shade or two of brown. Color weakens, huh? Surely he was kidding, or just being contrary. Or even deliberately misleading his conversant, as he loved to do. After all, when he bothered, wasn’t he a fabulous colorist? Think back to all the amazingly colorful paintings through the years. OK, don’t be giving me Analytical Cubism, or I’ll throw Synthetic Cubism right back at you. Not to mention all those glorious paintings of Marie-Thérèse Walter in the ‘twenties and ‘thirties, or the beautiful Dora Maar’s of the forties. And so on.

And yet, there’s something there. Picasso, the master draftsman knew that, in the beginning is the line. The contour, the modeling, the shading, all begins with the line. The line is the syntax of his commentary; the color just the punctuation. The color may be a pretty addition, but the meaning is generally in the line.

As a practical matter, though all of us Picasso lovers would simply die to surround ourselves with beautiful, colorful Picasso paintings, I suppose it’s safe to assume that you don’t have the budget for doing so anymore than I do. It’s gratifying to note that occasionally, even one who does, nonetheless collects Picasso prints. Although just about every significant museum of modern art today acquires Picasso prints, one of the best examples of this fervor was provided by Norton Simon, the industrialist and founder of his eponymous museum, who hoarded Picasso prints like they were going out of style. He acquired 710 Picasso prints but only five Picasso paintings. (A print dealer can only admire that ratio!) Clearly, he didn’t do it because, unlike many print collectors, they were the only Picassos he could afford, but rather because the print medium, especially in the hands of Picasso, the greatest print innovator of all time, gave rise to unique and breathtakingly beautiful artistic expressions. (Note the interesting essay on Mr. Simon’s approach to print collecting by Gloria Williams in Betsy Fryberger’s Picasso, Graphic Magician: Prints from the Norton Simon Museum.)

Prints are of key importance not only for Picasso lovers, but must also have been for Picasso himself. In 1935, Picasso imparted the following thought to Christian Zervos, his friend and chronicler, “It would be very interesting to preserve photographically, not the stages, but the metamorphoses of a picture. Possibly one might then discover the path followed by the brain in materializing a dream.”

Dora Maar actually produced such a photographic record of the creation of Guernica. Some of the progressive stages of The Charnel House were also photographed. But it seems to me that Picasso most thoroughly accomplished his ideal in printmaking. I am not aware of any statements of his or of his collaborators to this effect, but it is hard to imagine that Picasso was unaware that the restless explorations of his creative process were immortalized in his prints. After all, he famously worked and reworked many of his prints, and thankfully produced a printed record at many steps along the way. Proofs were pulled during the often numerous “states” of his prints (each time the artist paused in his creative process and requested an impression to be pulled, that impression becomes a state; a print often had but one state, in which Picasso was satisfied with the finished product the first time he had an impression printed, or it could have as many as twenty or more states). The early states were usually printed in very small numbers, often singly. Between states, he attacked his prints in various and increasingly innovative ways, all the while recording his wondrously transformative quantum bursts of creativity. Prints provided Picasso a medium well suited to his method, since, by burnishing the copper plate or the lithographic stone, he could subtract detail as well as add it in. He was clearly aware of the central importance of his subtractive proclivity, as he said to Zervos in the same conversation,

“In the old days pictures went forward toward completion by stages. Every day brought something new. A picture used to be a sum of additions. In my case a picture is a sum of destructions.”

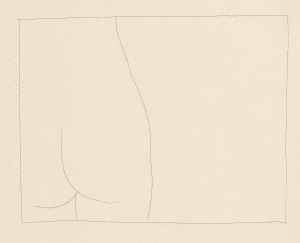

Although he had been speaking about his painting, perhaps the most well-known example of Picasso’s “destructive technique” is the eleven states of the lithograph entitled The Bull (1945-1946, Mourlot 17, Bloch 389), in which he toys with various conceptual ways of rendering the creature, initially complicating, but then mostly simplifying, his design until nothing is left but a pinhead and a simple, almost stick-figure outline. A similar example, not of progressive states of a print, but rather of closely related variations on a theme, is the series of nine wonderfully amusing lithographs of Balzac, eight of which were published in an elegant folio (Bloch 715 through 722).

Picasso not only had no financial incentive to produce prints, but he actually had a financial disincentive. Except perhaps in the case of some of his most simply executed etchings and lithographs, Picasso could have produced a painting or several drawings in the time it took him to work on a print. This is especially true in the case of the many prints which Picasso reworked again and again. In view of this financial disincentive, one can only conclude that Picasso must have really loved working in the print medium.

As for us, the wonders of his prints are more than enough to satisfy a Picasso collector’s dreams. His prints are a perfect medium for presenting his artistic accomplishments. In the hands of Picasso, the greatest artist and the most innovative printmaker of all time, the print medium gave rise to unique and breathtakingly beautiful artistic expressions not at all eclipsed by his achievements in painting, drawing, or sculpture.

Thankfully, Picasso’s prints, even though they’re not usually colorful, are strikingly beautiful in their own right. The reason we Picasso print lovers buy his prints, aside from their relative affordability, is not at all that we don’t love color, but rather that even “colorless” Picassos captivate us more than most brightly colored art by other artists.

To his credit, Picasso did so much with black, and with shades of gray, that he just about transformed them into a whole palette of colors. Through a myriad of invented techniques, now unknown and probably undiscoverable, he achieved, incredibly, almost three-dimensional, sculptural shapes on paper and remarkable shadow-play of white on black and black on white, to mention but a couple examples of his prowess in printmaking. (Though, interestingly, Ann Chernow, my friend, fellow art dealer, and an artist herself is doing her level best to reinvent his techniques.)

A client once told me the story of his early involvement in collecting Picasso prints. Initially he naturally found himself drawn to works in color. At the time, the art dealer who was mentoring him predicted that as the collector developed more experience, after he had examined many more prints, and after a requisite period of time had passed, he would naturally begin to gravitate toward Picasso’s works in black-and-white. This did in fact come to pass. Moreover, I have found this to be true of many collectors. Part of the reason is by force of sheer numbers. Though certainly there are some phenomenal colored prints, there are, to use round numbers, a hundred times as many phenomenal black-and-white ones. Second, the finer line which etchings allow and the interesting gradations of tone which Picasso achieved with aquatint and even lithography yielded dramatic results in his hands, generally with a greater degree of complexity and subtlety than possible with linoleum cuts. So fear not, you Picasso lovers, ultimately most of the action is really in black-and-white!

If I could reduce the reasons I love Picasso to just one thought, it would be that his style, design, and line are so evocative of emotion and convey so clear a perception of the to-the-bone character of his subject. In the same breath, I would have to add that he accomplishes this character portrayal and emotional evocation regardless of how complex, or conversely, how spare, his images may be.

Today, we take for granted the simplification of figural representation in art. We’ve seen it all before. But prior to, say, 1931, when, for example, the following etching was created (Bloch 125, Figure 1), a nude depicted as sparingly, just hinted at, in fact, had not yet existed as a finished artwork.

If an asteroid hit Paris or New York and blew up the Picassos into tiny shards, an art historian or even a layman with a passing familiarity with Picasso would have no problem distinguishing the pieces of Picasso paintings from all the other shards of art on the ground. An eye would be a giveaway; a hand or a foot would do. How about just one finger? A background decoration? Despite his hundred or so styles, Picasso’s unique stamp upon the canvas is almost irreducible.

Yet despite the common thread among them, Picasso developed numerous original styles, way more than any other artist in history. They numbered more than 80 by the early 1950’s, according to one art historian who bothered to count. At that time, he still had two more decades of feverish painting left in his run. And, amazingly, each and every one of his styles was a brilliant success.

Have you ever stopped to consider that artists and particle physicists have a lot in common? These scientists live in a world of specialization, much like artists, not to mention us mere mortals, and not unlike the subatomic particles they spend their careers chasing. Particle physicists are generally specialized as either theoretical, or experimental, particle physicists. It’s beside the point that, among their own kind, the theoreticians tend to sneer at the experimentalists when they think no one else is listening, on the premise that the experimentalists are really just glorified technicians, whereas they, the theoreticians, are really the brains behind the operation, with a monopoly on the creative talent. But of course that’s selling the experimentalists short. The experimentalists actually have two functions: devising an experiment in detail to test the theory, and then performing the experiment.

The artist’s job can be broken down along similar lines. The artist conceives of his project, plots its execution, and then executes it. Some artists are long on concept; most are rather short. Like physics experimentalists, the vast majority of artists just plot and implement the execution phase.

Picasso, of course, was a theoretician in spades. He deserves credit as the most creative artist by far and away who ever lived. His distortions of space and contour are also the most intellectual and complex in history. Yet if the net result of his efforts was not pleasing to the eye, or even riveting, he would not have achieved his stature at the pinnacle of the pantheon of art.

Picasso was also the greatest experimentalist who ever lived. His techniques, especially in printmaking, are so varied, unprecedented, and arcane that they are quite poorly understood. Ann Chernow, the artist and dealer who has embarked upon a project to try to recreate some of the effects Picasso achieved in her own printmaking, through trial and error has come up with a number of surprising possibilities. Gasoline with tar, no less!

A Picasso can make us laugh and rage and cry and think. As the artist said himself, “You see, a pot [usually mistranslated as casserole] too can scream…. Everything can scream. A simple bottle. And Cezanne’s apples!” (Pierre Daix, La Vie de peintre de Pablo Picasso; Paris: Editons du Seuil, 1977, p. 322)

But it’s not enough for an artist just to distort reality. In order to inspire the viewer to wander back to the work time and again, the distortion itself needs to be well conceived, well done, and intriguing and even pleasing to the eye.

Studying a Picasso can be a transcendental experience. A Picasso invites you to do a double-take. First you take in a gestalt of the subject and note the number of figures. Next, you check the distortions: How many faces do I see in this one head? Which ways are they looking? How much of a turn did the trunk of this body take? I see one breast but where’s the other? (It’s almost always somewhere, and in plain view.)

“Reading” a Picasso is not entirely unlike solving the riddle of an X-ray. After first grasping the overall image, or, sometimes of necessity, in order to grasp it, one finds oneself inescapably pulled into the art by the master prankster. The puzzles each viewer is invited to decipher, in whatever order, include accounting for the number and placement of all the facial features (What clever ways did he depict the eyes and ears this time?); identifying the various twists and turns and other distortions of the remaining physical features (With what enchanting, expressive touches has he endowed the hands and feet? On which sides did the breasts and butt show up?); perceiving his other visual puns, sundry allusions to literature and prior art, and any other hidden meanings; following the lines and spatial planes across the surface of the art as they unite disparate forms, tear asunder previously intact ones, and throw the pictorial objects and thereby the viewer completely off balance; or simply following the elegant neoclassical lines with which he alternately depicted his subject.

Picasso’s art has been called intellectual, but what exactly does that mean? I believe the term is meaningful on several levels. A fair amount of theory underpins much of his art, especially starting with Cubism. One needs to understand the theory or at least take the time to assemble the image from its component cubist parts in order to figure out what each work represents. In other words, to take it all in and to connect the dots, you’ve got to use your head.

Picasso, who has been called the greatest psychologist of the twentieth century, filled his canvasses with the counterpoints of beauty and despair. Picassos evoke the beauty of being alive, the beauty of love and joy, and, yes, the beauty even in anguish and tears. As such, it is surprisingly not hard to read Picasso, even in the depths of his despair, as a celebration of life. Picasso is about the dignity of life as well as about whimsy, humor, and, of course, unbridled sexuality.

Although you might say, especially in these troubled times, all of us have seen enough tragedy. Clearly we’re more suited for Picasso’s romantic comedy. But can one misread a Picasso? The next chapter will explore this thorny question.