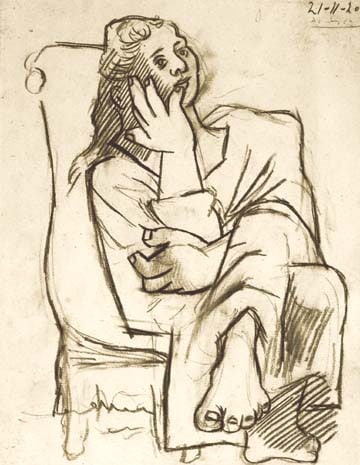

Seated Woman

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: Nov. 21, 1920

Medium: Conté crayon on paper

Dimensions: 279 x 210mm, 11 x 8 1/4″

Signature: Signed and dated “Picasso 21-11-20”, top right

References:

• C. Zervos, Pablo Picasso: Supplement aux volumes 1a 5, Paris, 1954, vol. VI, no. 1396 (illustrated).

• H. Chip and A. Wofsy, The Picasso Project : Picasso’s Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture: A Comprehensive Illustrated Catalogue 1885-1973, Neoclassicism I 1920-1921, San Francisco, 1995, no. 20-460, p.143 (illustrated).

• J. Palau i Fabre, Picasso: From the Ballets to Drama (1917-1926), Madrid, 1999, no. 882, illustrated p. 240, text reference p. 243.

• Mallen, Enrique, ed. Online Picasso Project. Sam Houston State University. 1997-2017. OPP.20:365 ills.

Provenance:

• Saidenberg Gallery, New York.

• Private collection, London

• Nancy Whyte Fine Arts, New York

• Galerie Hopkins-Custot, Paris

• L & M Arts, NY

Price: Sold

In 1917, Jean Cocteau arranged the first of several commissions for Picasso to design the sets for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe in Rome, and Picasso followed him there for a couple of months. This was Picasso’s first trip to Italy and his first real exposure to Greco-Roman antiquity. His sojourn in Italy was to have far-reaching consequences for his art. While all along adding to his vast panoply of synthetic cubist iterations, Picasso at the same time set out to capture Classicism and make it his own, and he did so, typically, in more ways than one. At one extreme, he created rather naturalistic renditions of Diaghilev, Stravinsky, and some of the dancers including Massine and his future wife, Olga. At the opposite extreme, he developed a novel idiom for creating sculpture without having to resort to hammer and stone–sculptural painting. He had already created one general style of sculptural painting, epitomized by Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, where the figures as well as the space surrounding them seem hewn out of rock. Now he created a new cast of characters, classical in their features right up until the moment he inflated their bodies to the bursting point like a turgid balloon.

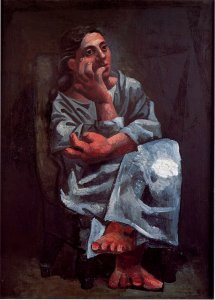

The drawing at hand marks the halfway point between the more realistic portrait drawings that preceded it and to which Picasso soon returned, and the sculptural paintings of the period, with one of which this drawing is closely related. That painting, which bears the same name as this drawing, Femme Assise, now hangs in the Musée Picasso (Paris) and is shown below:

In the cases of related paintings and drawings in Picasso’s ouevre, quite often the painting is by no means more accomplished or more beautiful than the corresponding drawing. Oil paintings bring possibilities of expression unique to that medium or to colored brush painting in general, but so do drawings. Paintings are usually larger in scale; drawings are often a more intimate affair, requiring closer viewing. In the case of this drawing and its related painting, the painting is certainly a great work. Yet some of the greatness of this drawing is lost in translation to canvas. The following is a pretty strong statement, but if the value of the drawing and painting were the same, I would choose this drawing.

According to John Richardson (Picasso: The Classical Period, New York, 2003, p. 15), these works were inspired by the the famous fresco, The Recognition of Telephus by Hercules, which Picasso would have seen while sojourning in Italy in the Museo Naxionale of Herculaneum. Both painting and drawing show the same apposition of hand to face, finger to mouth’s edge, as in the depiction of the central figure of this fresco. This drawing in particular, as well as one other closely related drawing, reveal Picasso’s take on the dreamy, lost-in-thought expression of this lady in plaster.

Of course, that’s where all resemblance ceases. The rest of these neoclassical compositions is purely Picasso’s invention. Richardson typically has a quite a number of fascinating insights to contribute to the art history of these works, including the following observations:

“Olga’s pregnant belly is sometimes said to have inspired the pneumatic look of the countless paintings that derive from the Two Nudes [1920]. In fact, he seldom if ever inflates the bellies of his Classical women. He inflates only their extremities—hands and feet, toes and fingers—and their faces: lips, noses, cheeks, eyelids. Picasso had recourse to the same devices he had discerned in the Farnese marbles: for instance, how the disproportionate widening of the bridge of a nose or the bananification of fingers enabled the sculptors of antiquity to monumentalize their figures. By using these devices against themselves to parodic effect, Picasso subverted the sacrosanct canons of classical beauty, especially those relating to proportion, just as, then years earlier, he and Braque had succeeded in subverting Renaissance laws of perspective by using them, too, against themselves.”

This seated woman provides an interesting insight into the workings of Picasso’s mind, or, more specifically, the flow of his creative juices, especially when regarding the tentative, initially more proportional rendition of the left hand, prior to its assumption of its final, gargantuan state. This progression presumably reflects Picasso’s realization that only comically swollen hands could suit his present purposes.

The right foot in this composition is by contrast disproportionally small and unfinished, which appearance may be elucidated by the following explanation. Shortly before Picasso created this drawing, Olga had broken her leg, an injury, as has been surmised, which ended her ballet career. This injury probably explains the hatch marks across the right foot, and its foreshortening as also seen in two other related drawings created that month, clues, typically veiled as was his wont, to a true life-event.

The full-blown expression of Picasso’s two-dimensional “sculptures” were for the most part saved for the more plentiful paintings of this style. He must have felt that painting was better suited for his colossal creations, whereas he clearly preferred a more delicate touch for this conté crayon drawing and the one directly related charcoal, as well as for several other stylistically, if not thematically, related works on paper of the period. This breathtakingly tender, poignant, revolutionary, yet amusing drawing has achieved immortality with a place of honor in Picasso’s pantheon.

It’s not just I who is wild about this drawing. Ever since we acquired it, employees of the two major auction houses on both sides of the Pond have been courting me with the offer of putting it on the front or back cover of their catalogues. And my friend, the artist and trusted art dealer Ann Chernow, believes it to be the best Picasso to have changed hands in years. Period. This is clearly a superlative drawing, but you may be wondering just how superlative. Having scoured the catalogues raisonnés of the years in which Picasso did her portrait (essentially 1917-1924), I have concluded that it is the very best drawing of Olga, bar none. There is one beautiful drawing of a mother and child that I consider as great, Mère et Enfant(1922, PP22-123, Z.XXX, 360):

They are not exactly portraits of Olga and the baby Paulo but perhaps neoclassical stand-ins for them. Furthermore, this more realistic drawing is not as interesting or Picasso-esque, and it suffers in comparison by lacking the humorous acromegalic distortions characteristic of the full-blown sculptural neoclassical phase of which the present drawing is an exemplar.

There is certainly nothing in the auction record that compares to the drawing at hand. The best work on paper of Olga to have been auctioned in recent years is the following:

This “pretty” picture, Portrait d’Olga (1920, pencil on paper), is admittedly larger than the work at hand but quite flat and uninteresting by comparison. Nonetheless, it fared predictably well, fetching $2,592,000 in November, 2006.

Finally, a brief word about the medium of our drawing. Picasso rarely used conté crayon, which is one more reason why this drawing is exceptional. Picasso’s line fairly glistens from its waxy pigment, rendering this portrait all the more striking.