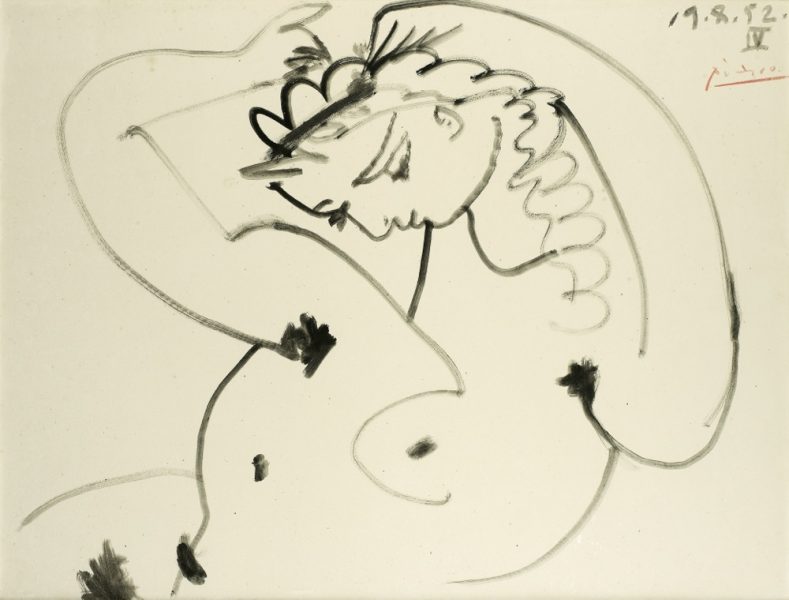

Woman Arranging Her Hair

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: August 19, 1952

Medium: Brush and ink painting on paper

Dimensions: 505 x 660 mm, 19 7/8 x 26″

Signature: Signed “Picasso” in red pencil and dated “19.8.52.IV”, upper right

References:

• C. Zervos, Pablo Picasso, Paris, 1976, vol. XXV, no. 220, illustrated pl. 127.

H. Chipp and A. Wofsy, The Picasso Project: Picasso’s Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture: The Fifties I, 1950-1955, San Francisco, 2000, no. 52-041, ills. p. 87.

• Mallen, Enrique, ed. Online Picasso Project. Sam Houston State

University. 1997-2017. OPP.52:178 ills.

Exhibition history: Pablo Picasso: Preoccupations and Passions, Naples Museum of Art, January 29-May 18, 2008

Provenance: Acquired in Paris circa 1959 by a private collector

Acquired by descent from the above

Acquired jointly by Evelyn Aimis Fine Art (Florida) and Connaught-Brown Gallery (London) in 2007

Price: Sold

Portrait of Madame H.P.

She sits almost like a heap of cut grass, laughing, immovable, riveted to the clouds and magnificently swept by the waves. The silver dish of her glance looks daggers at the tears dealt by fate, the crystals splashing their splendor against the window.

An incurable and inopportune thirst for azure presides over the prison of the condemned sinner….

A portrait done quickly, without erasures, India-rubber, or crumb of bread, under the soft curtain obscuring the sun. –Picasso

This serene brush and ink painting is one of Picasso’s unheralded masterpiece works on paper. It has lived in obscurity in the collection of a single family for almost fifty years, invisible to the world except through its photograph in Zervos. The following is my attempt to give it its belated due.

August 19th, 1952, was presumably a fine summer’s day, and Picasso made good use of it. It found him in the South of France, where he spent every summer since early on in his career. On this particular day, he picked up a broad brush and elaborated a new painting technique somewhat reminiscent, technically if not stylistically, of Asian ink brush painting, and made at least eleven known (or inferred) large portraits on paper of this lovely woman. Why “inferred”? Well, in addition to dating his works, in later years Picasso numbered the order of their creation on each day in Roman numerals. Both catalogs raisonnés, Zervos and Wofsy’s more recent Picasso Project, illustrate the works which Picasso created that day, all ink wash portraits, numbered I, IV, VI, IX, X, and XI. The others apparently have not yet come to light and may not have survived. In my opinion, number IV is by far the best of that day’s known works; I wouldn’t buy any of the others.

A new day, a new style. Just another way, in an endless procession of new ways, to reinvent the human figure, bending anatomic naturalism, as usual, in the service of expressionistic provocation. The style of this work looks deceptively simple, but it took all of Picasso’s preceding oeuvre to lead up to this day, just as he had to go through those many decades of refinement before he could seemingly cast them to the wind and achieve the breakthrough freedom and looseness of his last period, now known as Late Picasso. Picasso created this lovely brush and ink painting with sweeping brushstrokes, endowing his subject with flowing arms and torso. For her Greco-Roman facial features, he provided a harmonious riff on his earlier neoclassical work, with a result reminiscent of his portrayals in the early 1920’s of his friend Sara Murphy. In addition to the placid, contemplative facial features of this portrait, one’s eye is particularly drawn to the sweep of the arms, the depiction of the wavy hair and headband as if a crown, the gracile neck upon which the head appears to freely pivot—rocking impossibly, precariously forward, and the organic, anemone-like yet still other-worldly stylization of the fingers gathered to the task, gathered with the exception of the monstrous yet delicately extended pinky. One returns again and again to the single brushstroke with which he depicted the left breast and right shoulder. This wondrous, evocative painting is tender, spirited, free, and sensual.

Much more than in Picasso’s paintings, prints, and most types of works on paper, the brush and ink medium accentuates the individual brushstroke and thereby affords a rare insight into just how the artist created his art. Many of the lines within this painting are continuous and are clearly the result of single, long brushstrokes. It helps that there are not all that many brushstrokes in the entire work and that few of them overlap, so each can be traced from beginning to end. One can even infer the direction of each brushstroke by following its directional, gradual loss of ink.

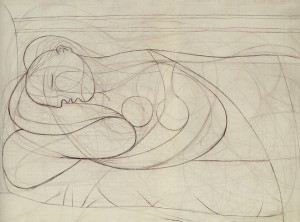

Although the style du jour is new, it is of course completely, recognizably Picasso, and has a number of antecedents in his oeuvre, such as the incredible 1932 Nu couché charcoal on canvas:

Then, there is an oil painting of 1935 (below) that bears the same title as our brush and ink painting. One should also consider the fabulous surrealist elongated creatures and blimps of the ‘twenties and ‘thirties, such as the 1936 Femme au vase de fleurs (OPP.36:020, PP.36:029), with which it shares the sweeping curve, if not the design of face and torso:

Femme se coiffant is related to Picasso’s delicate, voluptuous depictions of Marie-Thérèse beginning in 1932 and lasting until the start of the Spanish Civil War and Guernica, as well as coinciding with the beginning of the reign of Dora Maar, in 1937.

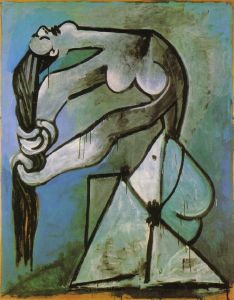

In some ways, our brush and ink painting bears a closer resemblance to a painting which followed it two months later, Femme nue se tordant les cheveux (OPP.52:157, PP.52:056):

These works are of course magnificent (and frankly bear only a passing resemblance to Femme se coiffant), but they do not eclipse the arguably greater freedom, spontaneity, and tenderness of this brush and ink painting. There are also some subsequent stylistic developments that have a glancing similarity to the sweep of the torso and arms of our painting. One need look no further than Picasso’s take-offs on the background figure of Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), which at the time of this writing are in our online catalogue: Femme Nue Pechant des Truites a la Main (Baer 1327).

Picasso first met Jacqueline around the time of our painting, but she didn’t enter his art until two years later. Its subject doesn’t quite resemble her any more than Françoise, with whom he was still living. Actually, this, as well as the rest of the known works of that day, are almost certainly portraits of Hélène Parmelin (1915-1997), a great friend of Picasso who, with her husband, the artist Edouard Pignon, spent much time at his home and together on the beach in Provence. An active member of the French Communist Party and writer for the journalL’humanité, Parmelin also wrote extensively about Picasso. Her books paint an intimate portrait of his life, character, and struggles as an artist. Picasso and “Madame HP”, as she was called, would often have heated debates on politics, other international issues, and modern literature. As a trusted friend and thinker, her opinions, especially on communism, were of great importance to Picasso and influenced the direction of his work during this period, as reflected in important works such as Massacre in Korea (1951-52) and the two large paintings War and Peace (1953) that are ensconced in his chapel.

Parmelin recounted the story of one of Picasso’s oil paintings of her, with an allusion to Femme se coiffant”s distinctive pose, as follows:

“Picasso often worked six or seven hours on end in the afternoons. From time to time, he would surprise us by holding an exhibition out of doors in the sunshine…. One day, he summoned us for a surprise. I had been ill with a bad sore throat. Pignon had surrendered to me his sultan’s iron bed in our room. And I was dozing on it one afternoon, all alone, with a temperature and strange nightmares in which the leaves of the olive tree outside the window played a horrible part…. My temperature was going up. Night fell at last.

“The door opened and a procession came in. I thought I was delirious. I screamed, then began laughing hysterically, my temperature went up like an arrow, and everyone was delighted and laughed till the tears poured down their faces, while they smoked whole packets of Gauloises. It was Picasso, Paulo and Pignon…playing at Spanish processions, marching round my room in hoods, their hands outstretched, clasping long stalks of lilies they had found somewhere or other …and singing in chorus at the tops of their voices and completely out of tune a De Profundis which would have made L’Homme au Mouton quiver with fright.

“I was prostrated. I protested. I had a temperature of 104…. Upon which, Picasso declared that with my hair loose I looked like a Courbet, adding—a usual joke of his—that it was such a pity one was not a painter! Because, if one had been a painter, one would have painted my portrait. He often alluded to it, indeed whenever I took out my hairpins to bathe in sea or sun.

“One afternoon, he summoned us, or rather whistled us up. He had a particular way of whistling as he opened the doors, which meant: come…. The doors of all the studios were open. And there, in the grass, propped against the little wall…there was seated a woman in green and blue, her feet bare and her hair loose, a woman who was I. I was myself; so was the canvas. I had been present at its birth…. I was living in the … studios of its creator…. I had not sat for it…. We were both sitting on the grass, I and the portrait—in the same pose.” (Picasso Plain: An Intimate Portrait, 1963, pp. 29-32)

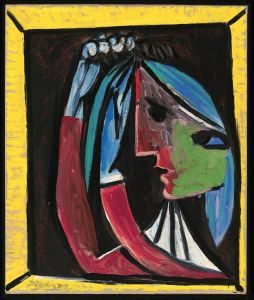

The oil painting which she described, Portrait de madame Hélène Parmelin sur fond vert (Spring~Summer, 1952), looks like this:

Picasso painted another oil that year which title also bears Parmelin’s name, and, in view of the actions of its subject, the woman wringing her hair illustrated above may be an unascribed portrait of her. None of these paintings look anything alike nor do they at all resemble Femme se coiffant or the other brush and ink paintings that day.

By this point you may be wondering how Parmelin really looked, if only to mark the point of departure for Picasso’s imagination. So here’s the best photo I’ve found so far, which seems to bear a glancing resemblance to the facial features and hair of the work at hand:

Femme se coiffant was profoundly rooted in the long-lasting affection that existed between artist and subject. Here Picasso uses brush and ink to startling effect, capturing the pose that so intrigued him. He may have found that the simpler medium of ink brush offered a certain freedom, in contrast to the large, heavily worked canvases that he also created of Parmelin. During this period of political anxiety—only a few years after World War II had ended and already the Korean War was well underway—these light-hearted and personal drawings must have provided an especially welcome relief from the intensity of his political paintings.

I had first fallen in love with our painting from a photo some nine months before and had been trying to negotiate a purchase or broker a sale intermittently ever since, to no avail. Then, in NY, having bombed at the auctions, I hurried through the Armory show en route to the airport, stopped to admire a nice Picasso cubist pencil drawing, turned the corner, and then this woman jumped me! My jaw must have dropped, I was so stunned by her beauty. I made an immediate offer and completed negotiations by cellphone a few minutes later. I found it amazing, not to mention a wee bit scary, to have completed this process, from the decision to buy it on the spot to the price agreement, soup to nuts in other words, for what to this two-bit art dealer is a major transaction, in less time than just about any other Picasso purchase I can remember. It’s just that it was so magnificent that I really had no doubts. (My word to the wise is, don’t try this at home.)

This work appears very painterly when viewed in person. This is hard to appreciate from a digital image, not only because the drama of the piece is heightened when viewing the large work in person, but also because the compelling boldness and charm of the individual brushstrokes, gradually fading in intensity before replenishment in the inkwell, are somewhat lost in translation. The photo also does not begin to do justice to the impressively large and bold red signature. It is of course impossible to convey the power and beauty of this ink wash in a photo, but I suppose I was sufficiently first impressed by its photo, so maybe you, too, will be.