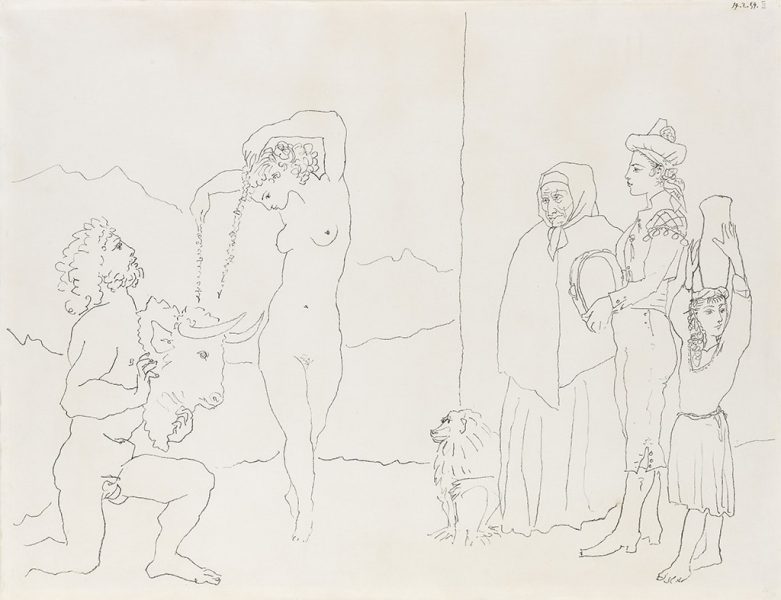

The Dance of the Banderilles

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: February 14, 1954, Vallauris

Medium: Lithographic crayon on transfer paper, transferred to stone

Dimensions: Sheet 492 x 645mm, 19 3/8 x 25 3/8″

Signature: The edition was signed in red pencil, which must have faded, unless this sheet somehow escaped Picasso (which doesn’t seem likely).

References: Bloch 752; Mourlot 248, Hatje Cantz 639, Rau 588, Reusse 639

Edition: Numbered 26/50 in a somewhat faded graphite pencil (probably due to prior cleaning). There were also 5 artist’s proofs. The edition was printed by Mourlot.

Paper: Arches; untrimmed

Watermark: Arches

Impression: Very fine

Condition: Deckled edges on all sides, with pale discoloration in parts of the bottom deckle; some skinning on top of the verso reinforced with japon paper pulp; otherwise fine

Price: Upon request

In his later years, Picasso wistfully evoked the subjects that had interested him in his youth, as he periodically looked back and took stock of his life and times. Despite his advanced age and, famously, his fear of death, this particular winter’s day caught him in a lighthearted, reflective mood. Perhaps he found his thoughts wandering from one of his iconic themes to another. More than likely, he already viewed these lifelong themes as inextricably interconnected. On this day, a full 50 years after Le Repas Frugal and his segue from the Blue Period to the Rose, he wove a number of them together and formed the narrative that is the beautiful composition at hand.

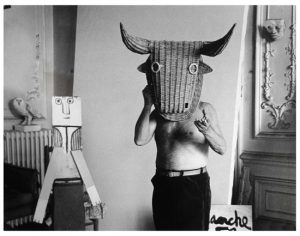

La Danse des Banderilles may seem lighthearted on the surface–it depicts a dance, after all, not an actual bullfight, but the dance is the “dance of death”. If this is take one on the dance of death, then take two occurred five years later in the series of linocuts of the bullfight (e.g. La Pique, Rouge et Jaune, B908). In the linocuts, the dance of death portrays an actual bullfight, however stylized. In the lithograph at hand, these are actors playing at bullfighting. The bull’s head reminds us of Picasso’s Minotaurs of the early 1930s, and none more so than the portraits of a young man, with classical features such as this man’s, who wears a Minotaur’s mask, as in the etching Minotaure, Buveur, et Femmes (B200) from the Vollard Suite. But here, the bull’s head looks rather realistic–for a mask–so that the viewer can’t help but wonder if it represents the decapitation of a recently breathing, snorting, charging beast. That interpretation does not strike me as consistent in the context of Picasso’s oeuvre, but I think Picasso, visual punster that he was, intended to force a double-take.

So what we have is a pas de deux with mask. It is a rehearsal, but we are not its only observers. The dancers are separated from a group of onlookers by a vertical line, a simple yet effective artifice which divides the composition into its two component parts. The group on the right tips us off that the entire entourage is a troupe of Saltimbanques, the traveling acrobats and circus folks whom Picasso immortalized in his Blue and Rose Periods. We see three generations of women: a girl balancing a heavy pitcher of water on her head, a young woman with tambourine, and an old woman, presumably the grandmother, along with their circus baboon.

Half a century after he first depicted them, Picasso revisited the theme of the Saltimbanque family in this lithograph and in several other lithographs in February, 1954, drawn once again to this idyllic, if offbeat, family life. His renewed preoccupation with the Saltimbanques may have heralded the end of his two month depression caused by the departure of Françoise Gilot, his mistress of 10 years, and their two children, Claude and Paloma. Perhaps he sought solace in the memories of his first mistress, Rosita del Oro, a star circus equestrienne in Barcelona. The strength of Picasso’s personality as well as his sexual precocity were evident at age fifteen, when he began a relationship with this adult woman, who was already well-known enough, as John Richardson records, to have merited her own poster.