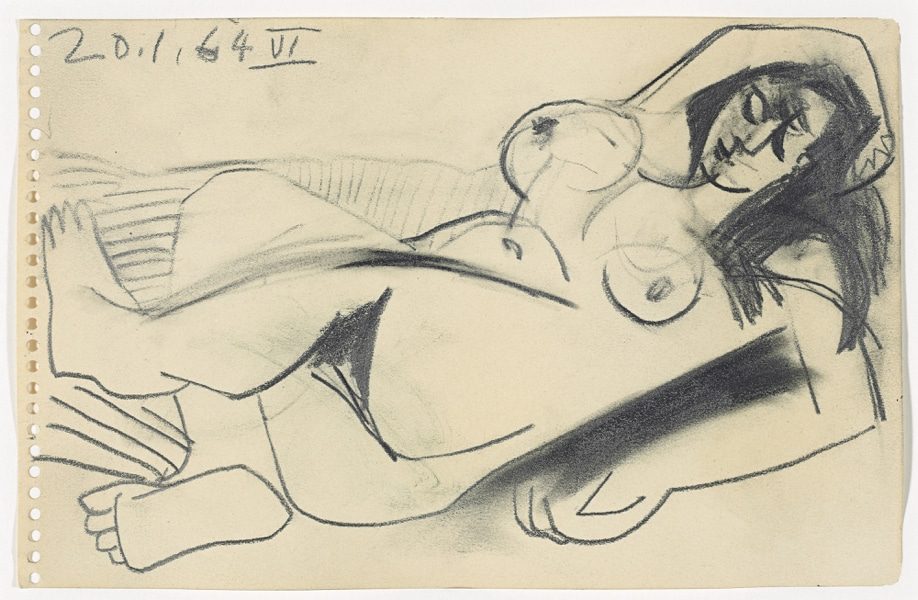

Reclining Nude

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: January 20, 1964

Location: Notre-Dame-de-Vie, Mougins

Medium: Mine de plomb, or lead pencil, according to Zervos, though it appears to be rendered entirely, or almost entirely, in charcoal

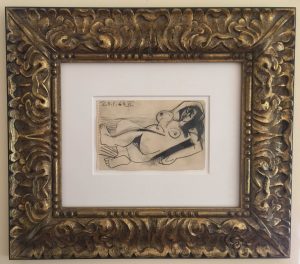

Dimensions: 13.5 x 21 cm, 5 5/8 x 8 1/4″

References:

• C. Zervos, Pablo Picasso, vol. 24, Oeuvres de 1964, Paris, 1971, no. 49 (ills. pl. 14).

• A. & M. Glimcher (eds.), Je suis le cahier, The Sketchbooks of Picasso, London, 1986, no. 173, p. 346.

• H. Chipp & A. Wofsy, The Picasso Project: Picasso’s Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture, The Sixties II, 1964-1967, San Francisco, 2002, no. 64-039, ills. p. 11.

• G. Schiff, Picasso at Work at Home: Selections from the Marina Picasso Collection, 1985 (ills. p. 145, prior to disassembly of the sketchbook).

• E. Beaucamp, et al., Pablo Picasso: Eine Ausstellung zum hundertsten Geburtstag [An Exhibit for his Hundredth Birthday], Werke aus der Sammlung Marina Picasso, Prestel-Verlag München, 1981.

• M. Müller, Pablo Picasso: Im Atelier des Künstlers, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, 2010, (ills. p. 191).

• Mallen, Enrique, ed. Online Picasso Project. Sam Houston State

University. 1997-2017. OPP.64:225 ills.

Provenance:

The artist’s estate

Marina Picasso, by descent from the above

Galerie Jan Krugier, Ditesheim & Cie, Geneva (inv. no. 11423)

Thomas Segal Gallery, Boston

Private collection, Switzerland

Exhibitions:

• Munich, Haus der Kunst, Pablo Picasso, Werke aus der Sammlung Marina Picasso, February – April 1981, no. 274, p. 412; travelling exhibition.

• Miami, Centre for the Fine Arts, Picasso At Work At Home, Selections from the Marina Picasso Collection, November 1985 – March 1986 (illustrated p. 145).

• Münster, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso, Pablo Picasso, Im Atelier des Künstlers, August – November 2010 (illustrated p. 191).

Price: Sold

Take a second look. I admit it—I had to! I passed this drawing the first time I looked at it, and it took a friend of mine to point it out before I stopped to reexamine it. Only after I had looked more closely (and surely that is what Picasso expected from his audience!), I realized the profound sophistication and beauty of this piece. So go ahead, take another look yourself. And this time, once you get past the subject’s luxuriously flowing hear, consider her face carefully. Note that this visage is an example, one of thousands, of Picasso’s two-faces-in-one signature style. What’s amazing about this iteration, and what makes it stand out from the rest, is the extreme economy of line with which he conveyed it.

So let’s make sure we’re on the same page. If your first glance was the same as mine, what you saw was a frontal view of the face. Certainly the subject’s eyes—all three of them!—look like they’re facing forward. Her mouth also gives that initial impression, but only by dint of a subtle indication of the left side of her lips. Then, you might notice that the more emphatic right side of her lips indicates a mouth in profile, as of course does the nose. You might also notice the resemblance of the fingers of her right hand to a face–have they entered her dreams in the guise of another subject’s profile? Picasso to his Jacqueline perhaps? Hard to say, but it would certainly not have been beyond the master punster to have intended this ruse. In short, there’s a lot more to this masterwork than first met my eye. So stop to take in this drawing now if you like, or read on if you prefer, as we explore it together….

They are, from one page to the next, from cover to cover, and adventure— a diary of the painter…. They are the notes working up to something or bouncing off something else, perhaps a sculpture onto a painting and back. The pages of the notebooks are the sketches for paintings but they are also often the afterwords. Sometimes they stand as elaborate works on their own. Picasso’s notebooks are stepping stones to trampolines for somersaults. – Claude Picasso (from the forward to A. & M. Glimcher, Je Suis le Cahier, p. 5)

“Je suis le cahier. (I am the sketchbook.)” So wrote Picasso on one of their covers. “That assertion of identity,” opined the editor of the eponymous catalogue raisonné of his sketchbooks, “is crucial to an understanding of the sketchbooks as vital and interdependent parts of the development of Picasso’s work. Conversely, we might say the sketchbooks are Picasso. They are the legacy by which we may decipher the process of Picasso’s creativity and understand the cohesive totality of his life work. Some of the sketchbooks are small enough to have been carried in Picasso’s pocket to cafés, bullfights, and on outings, to record events, responses to the environment, and interpretations of what he saw. Larger sketchbooks, sewn or spiral-bound, were used in his studio; these are volumes of preparatory and intermediary drawings in the service of picture making as well as statements complete in themselves.” (A. & M. Glimcher, Je Suis le Cahier, p. 2)

One could say this about much of his art, but it is especially in his sketchbooks where Picasso recorded his stream of consciousness, the spontaneous gestures of his unparalleled, boundless imagination. The sketchbooks present some of the most raw, unedited expressions of Picasso’s thoughts, a virtual EEG of his mind. When perusing their pages, one is transfixed by the intimacy of the drawings. But in Picasso’s lifetime, they were hidden from sight. As Françoise Gilot, herself an artist, explains, “Often painters need to record a fleeting thought, an observation, a new organization of shapes and colors. A sketchbook is a companion, a mirror of dreams, utterly sincere since it is utterly private and personal. From doodles to scamped or elaborate notations, it bears witness to the early processes of creation. Painters are usually reluctant to show these spontaneous notations, even though they may enjoy discussing a work with pen in hand around a bistro table and demonstrating the matter in question on the very paper that is laid down to protect the linen tablecloth. There is a difference here, since in a sketchbook the artist attempts to capture a new conception as it surges from the limbo of the unconscious, whereas at the bistro he or she publicly displays skill, wit, and well-rehearsed feats of virtuosity. Pablo Picasso was no exception: if he liked to show friends his recent achievements or to improvise freely in a café-brasserie, nevertheless he remained secretive about his sketchbooks; so I was quite impressed when, by the end of 1945 he started to show me some of the most intimate aspects of his work.” (A. & M. Glimcher, Je Suis le Cahier, p. 212) As for the rest of us, unlike the many other secrets Picasso took to his grave, at least access to his private sketchbooks has since been democratized–we can all see the contents of Picasso’s sketchbooks, which are faithfully reproduced in a number of catalogues raisonnés.

Picasso kept almost all his sketchbooks for himself. He may have ripped out a rare drawing and given it to a friend, but that would have been the exception. Apart from this theoretical exception, the drawings in the sketchbooks were unsigned. Picasso only signed the art he sold, and he would have had no reason to sign his private sketchbooks. The only lifetime sale of a sketchbook to my knowledge was to the famous art dealer, Heinz Berggruen. It dated from 1970 and was comprised of 26 erotic drawings. Berggruen’s son John, also an art dealer based in San Francisco, purchased the book from his dad, dismembered it, exhibited it in his gallery, and then consigned the sheets to Sotheby’s. Sotheby’s auctioned them in London on Feb. 9th, 2005, and, in general, they performed exceptionally well. A dedicated exhibition catalogue is still available today, entitled Picasso: The Berggruen Album, by Marilyn McCully and John Richardson (Mitchell-Innes & Nash, 2006). As you will see if you have a look, Nu Couché compares very favorably will all of them.

Since Picasso’s death, his notebooks have mostly remained intact. Nu Couché derives from one of the only sketchbooks that have been sold posthumously. Marina Picasso inherited this sketchbook, and I am aware of the sale of three of its drawings including this one, through her dealer Jan Krugier.

One of my pet peeves—not to imply that I have many—is the overuse of the term “sketches”, which I have heard applied even to the most accomplished of Picasso’s drawings. But this charcoal is undeniably a sketch. It is, after all, a page out of one of his sketchbooks. So was this sketch—er, drawing—a prelude to something else, a more finished work perhaps? This nu couché came from one of the final sketchbooks, number 173. Picasso inscribed both its front and back covers “17.1.64/23.1.64”. Its 33 pages of drawings thus spanned a full week. There was no apparent progression in this book—the sketches do not build upon each other or lead in any discernible direction. Their subjects include two wonderfully Picassoesque renditions of a chair and a page of three sketches for the Tête, the massive iron sculpture that Picasso donated to Chicago. (They are not the first sketches, however; the earliest dates at least as far back as May, 1962.) Otherwise, he filled the pages with nudes, mostly reclining, sometimes alone, at other times next to the artist at work or as one element within the artist’s studio. Most of the drawings are horizontal, some are vertical; one horizontal drawing is backwards (with the perforations on the right), unless it is possibly the verso of a double-sided drawing (though this is not confirmed in any printed or online catalogue raisonné). While filling this sketchbook, he created but two other drawings, a painter and his model in sketchbook number 174 and a bullfight dedicated to a friend (OPP.64:211), and he finished a painting with the same title on the 18th that he had begun on the 9th, a reclining nude very similar in pose to this drawing:

So, at least with respect to this drawing, the painting came first! But this is but a chicken-or-the-egg question, since countless drawings and paintings of reclining nudes both preceded and followed this week’s creations. And no other art that week, no larger drawings, no sculptures or ceramics, no prints that year at all till June, nada.

Of all the drawings in the sketchbook, this Nu Couché is the most similar to the painting. The attitude of the torso and extremities, and of the model’s head and her flowing hair are for the most part quite similar. But it is this exuberant sketch that really speaks to me. I am drawn to the subject’s beautifully rendered split-face and am charmed by the way it is engulfed by her overflowing hair. I find myself lingering for a moment on the clawed, raised hand, which evokes a face—a mere coincidence, or the subject’s lover? If anyone, it is most likely Picasso himself, since his default model, three years after their marriage, would have been Jacqueline, not to mention that this portrait resembles her, at least as much as most of her other portraits. Even the perforations on the left edge are charming, reminders that we are peeking into the artist’s private diary. This energetic drawing is a testament to the immediacy of Picasso’s conception. Still, he took the time to adjust a breast here, a leg there, leaving his tracks along the way, so that we become witnesses to the evolution of the portrait.

Late Picasso is in essence the epoch of Jacqueline, with whom he spent the last 20 years of his life and whom he married in 1961. As John Richardson has written, Jacqueline is the default subject in the portraits of this period. Some portraits clearly resemble her, but most do not. Although the features of Nu Couché resemble Jacqueline, they are also somewhat abstracted; therefore it cannot be said that its subject must be her. But the sketchbook from which it comes shows multiple full-room scenes of the artist’s studio, as well as depictions of the artist and his model, and some of the model alone. The extent to which these sketches derived from Jacqueline while she reclined alongside the painter, versus from an idealized model and atelier that sprang from his boundless imagination, is impossible to pin down. But of course Picasso took great liberties even in his most recognizable portraits. Picasso intended his art to come to life in its viewers’ eyes and be subject to our interpretation. So in the end, it’s all how we look at it, and upon which layers of meaning our thoughts choose to linger.

Today Late Picasso is all the rage. His later paintings were characterized by compositional looseness and freedom, whereas his later etchings were typically much more tightly constructed. But his drawings spanned this entire range, from the one extreme to the other. In this Nu Couché, the Late Picasso looseness multiplied by the spontaneity of the sketchbook yields a tender yet dramatic result.

This is in fact a quintessential Late Picasso nude. It has just about everything you could want from a late Picasso drawing: it’s beautiful, it’s sexy, it’s playful, complex, and ingenious. Drawn thick, bold, and dark, it truly “holds the wall”, all the more remarkably for a smallish piece. And it makes you wonder, as do so many great Picassos, now how did he do that?!