The Picasso print sale of the millennium just came and went (Sotheby’s London), so one would think it might deserve comment, not least of all because it was such a strong auction. Yeah, I know that’s a pretty bold statement, given that the millennium isn’t even half over. OK, so it was at least one of the two sales of the millennium. Depending on which prints you’re most interested in, you might prefer to nominate the Mourlot estate sale at Christie’s NY in 2003 for that honor. But the auction last week included Picasso’s two most expensive prints, and quite a number of other great works. It also set some world’s records, especially for the most valuable pieces. La Minotauromachie went for a hair under $2M, and an early state of La Femme qui Pleur (The Weeping Woman, Bloch 1333, the 3rd state of 7) fetched just over $1.7M, both more than doubling their recent auction prices. The Minotauromachie, which also set a world’s record for a single print by any artist, was a good, unsigned impression, well-inked and printed on good paper.

The sales of these two prints underscore the fact that although scarcity is certainly one of several factors in determining value, it is not the paramount one. We need only remember Giacometti’s Walking Man, who walked for a, 104,300,000 dollars to be precise and enjoyed a brief reign as the all-time auction high water mark, until he was deposed by Marie-Therese the next auction round. Yet there are nine other men just like him. The Minotauromachie is similarly not that rare. At a total of about 116 recorded proofs, its edition size is just about double the average Picasso print edition. The Weeping Woman is scarcer, with 39 proofs in all. (Fifteen signed impressions of each of the third and sixth states comprise most of these.) But the edition sizes of these two works are somewhat misleading, since they are so sought-after and since many of them by now must be in museum collections. For example, Artnet lists only 4 Weeping Woman sales at auction (the others occurred in 1994, 1997, and 2004).

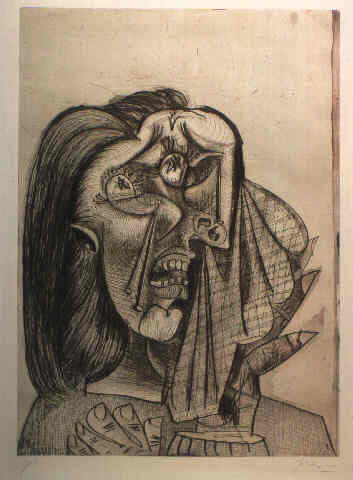

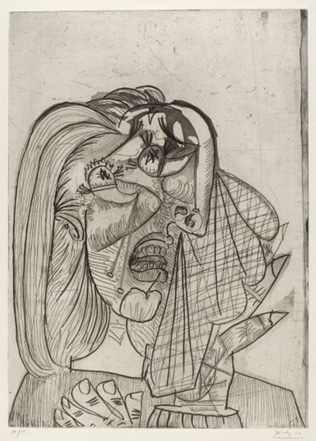

It is always interesting to compare states to get an insight into the progression of Picasso’s creative process. As an example, here’s last week’s La Femme qui Pleur, State III, followed by a photo of State VI:

The Wall Street Journal last month declared the end of the recession in the fine art market. (One hopes this proclamation is not as ill-fated as some other infamous pronouncements, such as Bush the Younger, who proclaimed the end of the Iraq war in 2003.) It certainly seems true with regard to Picasso drawings and paintings, which are on fire. But his print market had remained depressed until last week. The London sales show that the prices of Picasso’s pricier prints (those in the six figures or more, USD) have resumed the upward spiral of the pre-Crash market. One might argue that the great collection sold at Sotheby’s caused a feeding frenzy, but desire alone does not pay the bill.

The prices achieved for the less expensive prints were more varied but still generally depressed compared to pre-Crash levels. Makes sense: wealthy collectors by now are back in the fray, possibly as a hedge, given the loss of confidence in the stock market. By contrast, the collectors who concentrate on less expensive prints have diminished in number, many of whom must sadly have taken a big hit in the Crash from which they have yet to recover. Thankfully, there is a Picasso for every pot…but, I suppose, not necessarily one that every Picasso lover is willing to settle for. It’s all a matter of taste. In my opinion, a number of Picasso’s greatest prints are not among his most famous and can therefore still be had for a song. Under $10K, that is. Fortunately, the market at large does not share my opinion!

Picasso collectors whose means are not particularly limited may still want to know where the value is today. Where should the smart money go? Well, my crystal ball is as murky as anyone’s, but it has become clear to me that the best value in higher-priced Picassos today is in his drawings and other works on paper. Buying opportunities arise because one can still find a work on paper whose fame is not yet commensurate with its greatness. It is still possible for a masterpiece drawing to be unheralded, yet much less possible for a painting or print.

Why? The reason is simple: there is a lack of consensus regarding the hierarchy of his tens of thousands of drawings (roughly 20,000, I suppose). The paintings get nearly all the attention, of course. Museums typically keep their drawings tucked away in a flatfile, while their oily cousins flaunt their colors for all to see. There are many more drawings than paintings in Picasso’s oeuvre, by at least a factor of 10. There are also many more masterpieces among his unique works on paper than his prints. Perhaps because they are so plentiful, and/or because fewer people collect them, consensus has simply not been achieved. Ask any serious Picasso print collector about which are the top 3 prints, or the top 10 prints, and you’ll hear fairly close agreement. Not so with his drawings, not even close. One of my client collectors has observed that a few people, presumably collectors or dealers, set the standards among Picasso prints years ago, and the market has not yet shifted much since then. That may well be true, although one could argue that the art market pricing is more democratic than that.

Picasso print collectors have only around 2500 works to consider, most of which are illustrated in a single volume (including almost all the important ones). In part because his prints were usually printed in multiples, they come up for sale relatively frequently, so we have a chance to see them in person or at least in printed catalogues and online. A much smaller percentage of drawings comes on the market than prints, so that studying the drawings is mostly a function of online or textbook research, plus viewing the handful of drawings that surface, if you happen to live in or frequent New York or London.

The lack of a mature market for drawings is both good and bad. It could be bad when it comes time to sell, if in fact the market has not grown sufficiently wiser since you bought your piece. It’s good because lack of recognition of his masterpieces is precisely what provides the buying opportunity–the ability to pick up an unrecognized masterpiece for the price of an average work. Of course the availability of masterpieces is diminishing all the time, so it’s been getting harder to find not just treasures, but especially those treasures that have fallen through the cracks. But, now that the buying and selling freeze has passed, the Recession seems to be forcing a lot of work to market. For those of us still flush enough to be buying, now should be a good time to do so.