Among the ways the Stein collection (currently on view at the SFMOMA) can be viewed is as one family’s referendum on the time-honored debate among art lovers: Picasso versus Matisse. Those two artists contributed most of the significant pieces to the collection. Yet in addition to her brother Leo’s objection to Gertrude’s sapphic relationship, the disagreement that developed between these siblings as to who was the better artist, Matisse or Picasso, tore them apart, drove Leo out of their shared apartment, and caused each of them to divest most of his or her holdings of the artist who had lost favor. They’re presumably not the first couple to have suffered such a fate (though they may have been the first). The poet André Salmon bore witness to this century-old conflict in 1910: “There are lovers of art capable of admiring both Picasso and Matisse. These are happy folks whom we must pity.” If you just happen to be one of these happy folks, bear in mind that for a number of years brother and sister still admired and collected both artists. It took a while for their tastes to narrow, just as it may for you. Or not. But, beware, the battle lines are drawn!

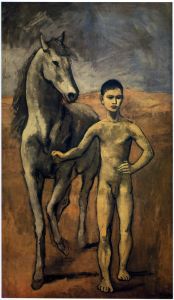

Another way to mine the lessons of the exhibit is in regard to the Steins’ uncanny collecting skills, which were instrumental in shaping the appreciation and acquisition of modern art for a century to come. In this vein, now that I’ve been to the exhibit twice now (and more to come–San Francisco is rarely graced by so many Picassos all at once; not to mention the large traveling loan from the Musée Picasso Paris that is about to go on display at the de Young) and having perused the exhibition catalogue between visits, it dawned on me that some of the greatest Picassos they had owned are absent from the exhibit. The curators went a very long way and were remarkably successful in assembling as many great Picassos as they did, as well as works by Cezanne, Matisse, and others. Among the “Stein Picassos” that are notably absent from the exhibit are, at least in terms of sheer value, three of the four greatest pieces they owned (two of these omissions are illustrated in the catalogue). Strictly in terms of market value, the “best in show” that is on the walls is of course the MOMA’s monumental Rose Period oil, “Boy Leading a Horse” (1905-6), for sure a $100M plus blockbuster if it were to come on the market today:

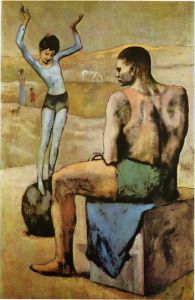

Almost, if not quite, as important is the following painting that fell through Gertrude’s hands:

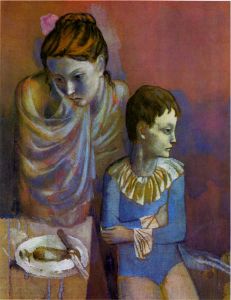

Young Acrobat on a Ball (1905)

This one she owned for a short while but later traded Kahnweiler, Picasso’s almost lifelong dealer, along with 20,000 Francs to sweeten the deal, for three cubist and proto-cubist paintings. The group she acquired doesn’t add up in beauty, importance, or value to the single piece she lost, let alone with the 20,000 Francs thrown in, proving Kahnweiler’s superior eye. Then, there were the following two amazing, oversized goauches:

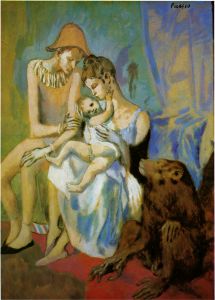

Family of Acrobats with Monkey

(1905; gouache, watercolor, pastel &

India ink on cardboard canvas)

Mother and Child (1905; gouache)

The Family of Acrobats with Monkey is one of the first two Picassos that either sibling acquired (Leo), almost as soon as it was dry. Wouldn’t you say that these two works compare favorably to the following gouache:

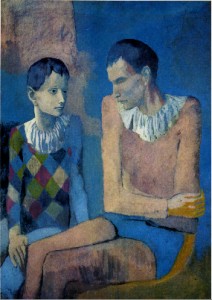

Acrobat and Young Harlequin

(1905; gouache on cardboard)

I’ve drawn the comparison because the three gouaches are of similar greatness, subject matter, style, year, and size, and this last one set the world’s record for a work on paper at auction (or at least a Picasso work on paper) at over $38M, a record that still holds a quarter of a century later. Kahnweiler or no, the Stein kids had a great eye. And they surely benefited from having sought out the right place at the right time. It didn’t hurt that they also had a pocketful of change….