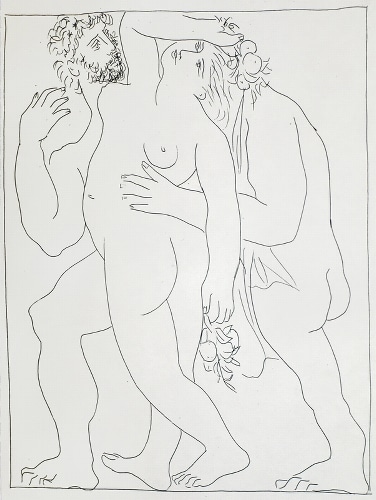

Vertumnus Woos Pomona

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: 1930

Medium: Etching on copper

Dimensions: Print 312 x 224mm, 12 5/16 x 8 13/16 “; Sheet 324 x 257mm, 12.8 x 10.04”

Signature: The edition was unsigned.

References: Bloch 126; Baer 144; Cramer 19

Edition: From the edition of 95, of the total edition of 145 printed by Louis Fort in 1931 before the cancellation of the plate

Paper: Arches laid; untrimmed; deckled edges at right and at bottom

Watermark: Arches à la main

Impression: Very fine

Condition: Fine; framed

Price: Upon request

Picasso didn’t hesitate to assign his audience work. His toughest assignments of course involved decoding his Cubist art. Here, in this Neoclassical etching, Picasso poses a more lighthearted question: how many people do you see? Go ahead, count them!

Three, huh? Now count the number of extremities, and heads, and torsos.

This beautiful artwork is a measure of Picasso’s creative genius in conceiving this delightful visual pun, and of his draftsmanship in pulling it off to perfection. There are a number of tricks he played, to our amusement (and no doubt his own). Apart from the obvious one (how many figures are there?), be sure to also notice the contrivance of a single line defining two structures. In the very center of his design, note the line that defines the right buttocks, and observe that this single line also defines the shape of this figure’s left wrist and forearm.

As I was taking my then 8-year-old son through this perceptual exercise, he responded by reciting a few lines from The Sneetches, by Dr. Seuss. Here’s how they went:

“…until neither the Plain nor the Star-Bellies knew

whether this one was that one… or that one was this one

or which one was what one… or what one was who.”

Here’s a bit of the backstory behind this masterwork: Albert Skira was just starting out in the publishing business when he decided to shoot for the stars and ask Picasso to illustrate a book for him. Picasso agreed but was at a loss as to which book to choose to illustrate. After some time, Picasso related a dream to Pierre Matisse, the artist’s son, in which women were transformed into fish. Pierre seminally proposed that Picasso illustrate Ovid’s Metamorphoses. For his fiftieth birthday on October 25, 1931, Picasso received the first proof of this book from Skira.

There could be no better fit between text and illustrator than a story of transformation, the very hallmark of Picasso’s art. The thirty wonderful and deceptively simple portraits that comprise this series include fifteen half-length portraits which illustrated the chapter titles and bore no specific relationship to the text. The full-length works did however closely correspond to the narrative, which was unusual in Picasso’s illustrated books. This series was created contemporaneously with the earliest prints of the Vollard Suite, with which it shares the simple elegance of the artist’s Neoclassical style.

Roland Penrose, one of Picasso’s primary biographers, was particularly impressed by Picasso’s Ovids because of their “astonishing perfection of line”. (R. Penrose, Picasso: His Life and Work, 3rd Edition, p. 264) “In his graphic work of the 1930’s, the artist often displayed a strongly classical spirit, but his line is never static or conventional—rather subtly distorted to give a sense of freedom and movement.” (The Artist & The Book, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 224)

This particular image is easily the most beautiful and the most interesting of these etchings, and it is also one of the two most important ones.

**********

In Roman mythology, Vertumnus was the god of seasons, change and plant growth, as well as gardens and fruit trees. Pomona was a wood nymph, a goddess of fruitful abundance. Her name comes from the Latin word pomum, meaning apple. For you mythology buffs, here’s a translation of part of the Pomona and Vertumnus story, provided by A.S. Kline:

“No other hamadryad, of the wood nymphs of Latium, tended the gardens more skillfully or was more devoted to the orchards’ care, hence her name. She loved the fields and the branches loaded with ripe apples, not the woods and rivers. She carried a curved pruning knife, not a javelin, with which she cut back the luxuriant growth, and lopped the branches spreading out here and there, now splitting the bark and inserting a graft, providing sap from a different stock for the nursling. She would not allow them to suffer from being parched, watering, in trickling streams, the twining tendrils of thirsty root. This was her love, and her passion, and she had no longing for desire. Still fearing boorish aggression, she enclosed herself in an orchard, and denied an entrance, and shunned men.

“What did the Satyrs, fitted by their youth for dancing, not do to possess her, and the Pans with pine-wreathed horns, and Silvanus, always younger than his years, and Priapus, the god who scares off thieves, with his pruning hook or his phallus? But Vertumnus surpassed them all, even, in his love, though he was no more fortunate than them. O how often, disguised as an uncouth reaper, he would bring her a basket filled with ears of barley, and he was the perfect image of a reaper! Often he would display his forehead bound with freshly cut hay, and might seem to have been tossing the new-mown grass. Often he would be carrying an ox-goad in his stiff hand, so that you would swear he had just unyoked his weary team. Given a knife he was a dresser and pruner of vines: he would carry a ladder: you would think he’d be picking apples. He was a soldier with a sword, or a fisherman taking up his rod.

“In short, by his many disguises, he frequently gained admittance, and found joy, gazing at her beauty. Once, he even covered his head with a coloured scarf, and leaning on a staff, with a wig of grey hair, imitated an old woman. He entered the well-tended garden, and admiring the fruit, said: ‘You are so much more lovely’, and gave her a few congratulatory kisses, as no true old woman would have done. He sat on the flattened grass, looking at the branches bending, weighed down with autumn fruit. There was a specimen elm opposite, covered with gleaming bunches of grapes. After he had praised it, and its companion vine, he said: ‘But if that tree stood there, unmated, without its vine, it would not be sought after for more than its leaves, and the vine also, which is joined to and rests on the elm, would lie on the ground, if it were not married to it, and leaning on it.

“But you are not moved by this tree’s example, and you shun marriage, and do not care to be wed. I wish that you did! Helen would not have had more suitors to trouble her, or Hippodamia, who caused the Lapithae problems, or Penelope, wife of that Ulysses, who was delayed too long at the war. Even now a thousand men want you, and the demi-gods and the gods, and the divinities that haunt the Alban hills, though you shun them and turn away from their wooing. But if you are wise, if you want to marry well, and listen to this old woman, that loves you more than you think, more than them all, reject their vulgar offers, and choose Vertumnus to share your bed! You have my assurance as well: he is not better known to himself than he is to me: he does not wander here and there in the wide world: he lives on his own in this place: and he does not love the latest girl he has seen, as most of your suitors do.

“You will be his first love, and you will be his last, and he will devote his life only to you. And then he is young, is blessed with natural charm, can take on a fitting appearance, and whatever is ordered, though you ask all, he will do. Besides, that which you love the same, those apples you cherish, he is the first to have, and with joy holds your gifts in his hand! But he does not desire now the fruit of your trees, or the sweet juice of your herbs: he desires nothing but you. Take pity on his ardour, and believe that he, who seeks you, is begging you, in person, through my mouth….”