2015 and -16 were the years of unnatural disasters. For us, anyway. I’m referring to conservation disasters. Not Trump’s anti-EPA EPA appointment, not that kind of conservation. No, today I’d like to tell you about our paper conservation disasters, because, as unfortunate as these events were, they are also teaching moments. I’ll share these case studies with you in order to arm you against the kind of conservation quandaries you may well eventually encounter, provided only that you don’t break yourself of the bad habit of collecting.

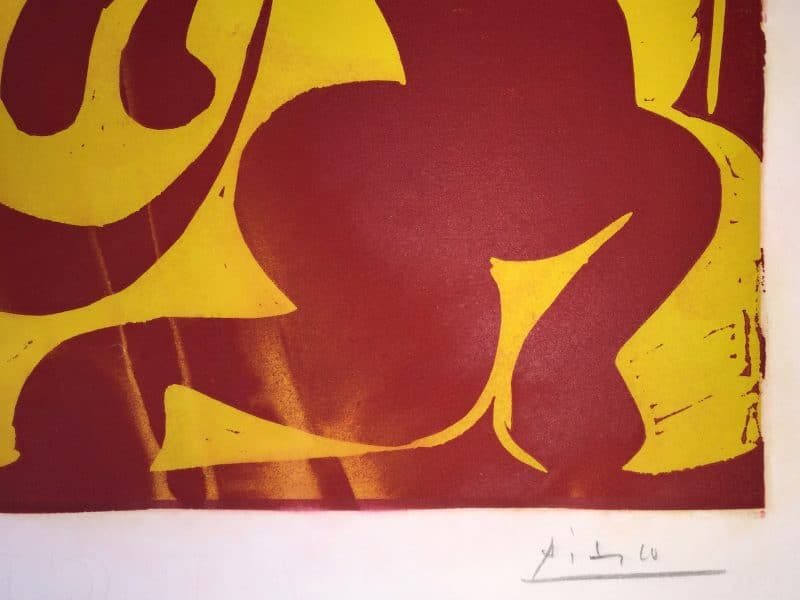

Our slide into conservation hell started with the ruination of one of the two impressions we had at the time of Pique, Rouge et Jaune (Bloch 908, above). The other impression was in fine condition, but this one had particularly toned margins and something that resembled paper pulp stuck along one corner of the image. When I dropped off the piece and pointed out the adherent pulp, the conservator dabbed at the pulp with a moistened a Q-tip, remarked that red pigment had transferred onto the cotton tip, and questioned whether the pigment was original. I responded that all the pigments were original and asked whether the piece was amenable to conservation given that the pigments, or at least the red, was apparently not colorfast. She assured me that she could carefully resolve the issues in a suction table rather than with full water immersion and all would be fine. Fast forward to our next visit, when I witnessed that much of the red all over the linocut had bled into the yellow background and that she had colored a couple of spots with a red pigment of her own quite different in appearance to the original red. Later I noticed that she had also overwritten the edition numbering. It had lightened during the course of successive treatments in which she tried to remove the red that had bled into the yellow. She had thereby turned a largely ruined but still original print into a partial forgery. But that’s not all. This actually turned out to be a triple whammy: I next learned that she had no insurance (insurers do not underwrite conservators in the USA) and that our own art insurance policy did not cover conservation mishaps. Nice.

As the saying goes, a little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing. I don’t pretend to fully understand the art and science of paper conservation, not even close, but I know a ruined print when I see one, and by now I have a better understanding of what can go wrong. It follows that it is vital to choose a well-educated conservator and one—I can’t believe I have to say this—who knows right from wrong. Having subsequently delved into the particulars of accreditation, I have learned that there are salient differences in the education and accreditation of conservators, such that it is insufficient to choose a conservator, as I had done, solely on the basis of personal recommendation. As it turns out, anyone can hang a shingle as a conservator (just like art dealers), yet not all conservators “are created equal.” There is a hierarchy of the quality of conservation schools with which I am to date insufficiently familiar, but a good conservator could have been educated at a lower ranked school, and vice versa. And it is not enough for the conservator to be a member of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC), for as their website states, “Anyone can be a member of AIC. All one has to do to become a member at the Associate level is pay the annual membership dues.” More importantly, it goes on to differentiate among its members as follows: “However, members with professional designation are conservation professionals who have had their training, knowledge, and experience reviewed by a body of professional conservators who are recognized in the field for their commitment to the purposes for which AIC was established.” The AIC confers two levels of “professional designation”. A Professional Associate must (and I quote):

- have earned an undergraduate university degree or the international equivalent (a waiver may be attained by writing to the Membership Committee explaining any equivalent education)

- have two years (2) of full-time formal education or related supervised training in a field appropriate to other professional involvement in conservation (e.g., chemistry for conservation scientists, library science for library preservation administrators, art history for museum conservation administrators, business management for administrators).

- have three (3) years of full-time work or its part-time equivalent in conservation or in a conservation related profession after training. Program training internships may not be counted toward this requirement.

The highest level of membership is as a Fellow, who must:

- have two (2) years prior membership with Professional Associate designation.

- must have a minimum of ten years of experience after conservation training or part-time experience which equals ten (10) years of full-time experience. Such experience should have enabled an individual to develop considerable professional skills and judgment with demonstrable achievement in such areas as conservation treatment practice, scholarly research, education, scientific investigation, and preservation management. Post-graduate fellowships or internships may be included in the required 10 years of experience.

In their description of the application process, the AIC goes on to say that the Fellow candidate must, among other prerequisites, “submit at least 4 examples of their work which shows evidence of sustained high-quality professional skills and ethical behavior” and “be sponsored by five (5) members with Fellow status who are personally acquainted with and knowledgeable about their work. “

A Professional Designation has less stringent requirements but is also dependent upon peer review and should be adequate. As Andrea Pitsch, a well-regarded NY conservator who has done fine work for us, pointed out, it also helps to have a Master’s in Art Conservation from a reputable school. She continued, “It’s the closest thing to licensing or certification that we have. Look these people up on the AIC website and find out their professional standing within the organization.” Of course you also have to make sure that the AIC has conferred Associate or Fellow status in the specialty in question, such as in this case, paper conservation. Suffice it to say that now my go-to local paper conservator, Karen Zukor, whom I have also employed over the years, is a Fellow.

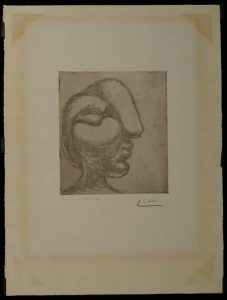

The saga above retells what can go wrong after the initial damage to the art has already occurred. But things can go wrong with art in perfect condition even after it is in your care. For instance, you have to choose an honest and competent framer. As the next story goes, I purchased a Vollard Suite etching over a decade ago for a collector from a gallery in the highest-rent district of Beverly Hills. She wanted it without the frame, and the frame was lovely, so I inserted a favorite etching (B256) into it. The sheet was larger than the opening of the frame, so I did so myself simply with archival corners. This was a custom, carved, gold-leaf frame with a prominent gold-leaf fillets (sp?) (the gold rim between the art and its surrounding front mat) which must have cost a pretty penny, so I did not suspect that the framer would have tried to save ten bucks by using acidic mats. Fast forward to this year, when I sold the etching but, once again the collector wanted it without the frame. So when I dissasembled the frame, I was shocked to behold that the previously pristine sheet had developed moderate mat-burn in the peripheral margins of the recto (the front side of the etching), especially in the four corners where the etching was forced by the plastic corners into closer apposition with the acidic front mat, yielding a peculiar mat-burn that looked like this:

(very near the corner)

The verso (the back side of the print) was in a much better state, as the back mat was archival (non-acidic). The extent of the mat-burn was such that I was pessimistic it could be entirely reversed. Karen was however able to reverse the burn completely all around, leaving a barely detectable trace of it only in the top left corner. When I afterwards reminded her of my initial pessimism, having seen lesser conservation results in cases of even less deep mat-burn, she said that the degree of potential improvement is dependent upon the type of paper and cannot generally be predicted in advance.

I picked up a simple trick of the trade not long thereafter, a pH-testing pen that costs less than 10 bucks on Amazon. Had I applied it to the mat, I could have prevented this unfortunate event. As Reagan said, “Trust, but verify.”

What else can we learn from these mishaps? For one thing, if you’ve purchased an artwork that requires restoration and it is located in a country (such as the UK) in which conservators’ work is insured, consider commissioning the restoration before importing the piece.

Secondly, if you’re acquiring the piece from an art dealer, let them bear the risk of restoration, not you. Many art dealers, ourselves included, will already have had the art restored prior to offering it for sale. Clearly, this adds value and limits your risk, so consider us favorably when next you’re out shopping.

Another lesson here may be, when it comes to condition, don’t be too fastidious. Some condition issues may be significant, like tears or discoloration of the image, but others may not be. Also, what bothers one collector may not the next, or the next may even consider it an advantage. Bear in mind that, although your eye may be drawn to any imperfections at first, over time they will likely recede in your mind as you focus more on the beauty of the art. I’ve seen that happen among our collectors, as well as in my own case, time and time again.

As an example of what I would consider an insignificant condition feature, take paper “waviness”:

The waviness may not be present at the time of acquisition but may well develop over time, especially with the thinner kinds of paper that Picasso often used. Recently I saw a label on the back of a frame that went something like: Gentle waviness of the sheet may occur over time as a function of ambient humidity. This may be considered not so much a condition issue or flaw but as a manifestation of the natural interaction of your work on paper with its environment. I would add that the waviness could even be considered a good thing, aesthetically speaking: it adds a certain three-dimensionality to your sheet, gives it physical gravitas, and makes it more of an object in space. And in my experience, waviness is usually limited to the margins peripheral to the image, so it doesn’t affect the appearance of the art itself. If limited to the peripheral margins, you could hide it by simply overmatting.

Sheet toning, if mild in extent, may also appear desirable, if for example the sheet now has a rich ivory hue, which sets it off nicely relative to the lighter, off-white surrounding mat.

Finally, in all fairness, I should add that the conservator who ruined our linocut had done a lot of good work for us over the years uneventfully. That history could be viewed as a testament to the relative safety of the profession. So don’t be too scared, just scared enough….