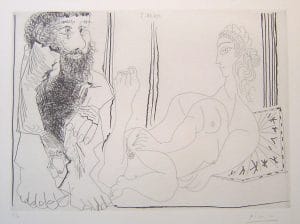

Homme Sangeur (B1768)

A testament to Picasso’s love of printmaking is the plethora of prints which he created in his final years, at a time when he surely knew his days were numbered. In particular, he created his two largest series of prints in this last period, namely, The 347 Series in 1968, aptly named for, you guessed it, the number of etchings and other intaglio prints it comprised. Then there was The 156 Series of 1970-72, completed within just over a year of his death. And you’re right again–it consists of that many prints. Compare this output to the sum total of all of his unique works of 1968, including paintings, drawings, and sculptures, which equaled 250 works. In the second series, although the ratio reverses, the prints still represent a large part of his oeuvre.

There are several salient features of these two series. They generally comprise etchings, aquatints, or some combination of the two. Though they vary greatly in size, they tend to be dominated, often hilariously so, by the subject of sex. Brothel scenes and sex between individual couples are common. The former often contain a portrait of Degas, whose sketches of brothel scenes Picasso had recently acquired. These brothel scenes contain a delightful assortment of consenting adults and voyeurs, including a priest in the latter category.

Whereas the brushstrokes of Picasso’s paintings of the period are the largest of his life and the depictions are similarly among the sparest of his long career, the prints in contradistinction involve as fine a line as ever. Picasso seems to have been saying through these prints that even as a nonagenarian he still had a razor-sharp gaze and steady hand—if his paintings tended toward abstraction, it was by choice and not as a product of his old age. His advancing age did of course take its toll in other ways. But although his virility is believed to have waned a decade prior to his death, clearly his mind delightfully remained in the gutter!

John Richardson, Picasso’s principal biographer, describes the themes of Picasso’s late drawings and prints as follows. Though chiefly writing about a raft of drawings that Picasso gave to his chauffeur Maurice Bresnu, this passage characterizes the late Picasso prints just as well:

“As a result of an ulcer operation in November 1965, Picasso had given up traveling and become something of a recluse. Except for his wife Jacqueline, her daughter Catherine, the Bresnus [his chauffeur and the chauffeur’s spouse] and a few professional associates (notably the Crommelynck brothers who worked on his prints), he saw very few people. To extend the cast of characters in his imagery, Picasso was obliged to invoke figures from his past as well as from his pantheon of favorite painters. Hence, former mistresses, Barcelona whores, harlequins and circus folk from the Rose period rub shoulders with personages from the work of Raphael, Rembrandt, Goya, Ingres, Degas and van Gogh, and sometimes the artists themselves. Thanks to these revenants, Picasso managed to merge the past with the present. The studios at Nôtre Dame de Vie, his villa at Mougins, became a microcosm of his universe-what Gert Schiff called Picasso’s Teatrum mundi….

“Just as Mendelssohn came up with Songs without Words, Picasso came up with stories or plays without texts. He provides only the illustrations; it is up to us to discern the plot and guess at the hidden links. Old age is the principal theme of these dazzling drawings, in which the sardonic artists allegorizes ruefully but never self-pityingly the humiliating plight of an eighty-nine year old Lothario with a burnt-out libido. The resultant images are dream images. As in a dream, everything—time, place, identity—is in a state of flux. Especially relevant to this sketchbook is the fact that at the age of fourteen, Picasso took as his first mistress on equestrienne called Rosita del Oro, and that, a lifetime later, she reappears in different guises, first of all in his prints and then, as here, in his drawings….

“Another ghost from the past is Celestina, the procuress immortalized in Fernando de Rojas’s famous fifteenth century novel, which Picasso had illustrated two years earlier. In this sketchbook he portrays not only Celestina and others of her ilk as wrinkled hags, but the courtesans who work for her and the clients she serves—gap-toothed, singing or laughing cavaliers, out of Franz Hals as well as Rembrandt. (These terrible teeth suggest that Picasso himself was having dental problems)…. It is typical of the artist’s shamanism to exorcise the aging process by depicting its symptoms.

“Picasso’s sexual powers may have waned—impotence is thought to have set in around his eightieth year—but sex was still very much on his mind. ‘We don’t do it any more, but the desire is still with us,’ he told Brassai. To compensate for his loss of libido, Picasso came to see sex and art, the brothel and the studio, as metaphors for each other—the sexual act standing for the creative act, and vice-versa. Hence the explicitly erotic nature of so many of these late drawings.” (Cavaliers and Courtesans: A Collection of Picasso Master Drawings and Ceramics, Christie’s NY, 1998, pp. 6-7.)

While discussing his 347 Series with his friend, Roberto Otero, to whom he had shown some of these etchings, Picasso said, “Of course, one never knows what’s going to come out, but as soon as the drawing gets underway, a story or an idea is born. And that’s it. Then the story grows, like theater or life—and the drawing is turned into other drawings, a real novel. It’s great fun, believe me. At least, I enjoy myself no end inventing these stories, and I spend hour after hour while I draw, observing my creatures and thinking about the mad things they’re up to. Basically, it’s my way of writing fiction.” (Roberto Ortero, Forever Picasso: An Intimate Look at his Last Years, New York, 1974, p. 170)

Half a year later, Picasso said the following about the prospective publication of this series to Otero, “You know, Louise Leiris is about to exhibit my latest engravings. And there’s one series that is quite innocent—I mean, quite natural. Well, you can imagine what they are about: Raphael and La Fornarina—his famous model—making love. Well, there’s no need to exaggerate—it’s not all sex, Raphael is painting in many of them, too—but Michelangelo is also there, spying on them from behind the draperies or under the bed. And sometimes the Pope is peeping through the keyhole, or some other important character is lurking about. Anyway, they have to do with certain facts—I would call them historical facts. And do you know what they’ve told Madame Leiris? They’ve told her she will not be able to publish a catalogue, that it can’t be bound. She’ll have to publish loose pages, without sewing them together!” (Roberto Otero, pp. 178-9)

Many of the artists that Picasso depicted later in life are considered self-referential. Kirk Varnedoe, the late, great Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the MOMA, has noted that Picasso’s self-portraits of the 1950s and 1960s were not so much faithful representations of the artist’s likeness as idealizations of an “artistic identity”. In an essay about these self-portraits, Varnedoe wrote, “The one avatar Picasso embraced most consistently in his final decades was the one with the least disguised self-reference: the figure of the artist. Near the breakup with Gilot, he undertook a series of drawings, often lightly satirical, of the artist in his studio, some of which were published in Verve in late 1953; after that, one or another variant of this theme recurred at intervals, especially among his drawings and prints. The focus was not on his own circumstances. Neither live models nor traditional palettes, which are constant attributes of these late studio scenes, had anything to do with his practice, and the artists in question almost never display his figures in more than allusive fashion; they tend to be stock types, typically bearded, which Picasso never was. Here, as in the case of countless male busts or figures, Picassoesque combinations of traits can come and go within a series in a way that suggests we may risk a certain arbitrariness in singling out one or another as an authentic self-examination.

“As he dwelled on the image of the older artist Picasso in his last twenty years also sought to fraternize and contend with a pantheon of painters of the past…. Certain of the generic busts and images of artists took on costumes or features that associated them with particular painters from history…. The practice began in greater earnest…after Picasso’s illness and surgery in 1963, and seems to have centered most tellingly on the disparate figures of Rembrandt and van Gogh.

“As Richardson has pointed out, these two artists may have been special cases for Picasso precisely because they are so strongly identified with self-portraiture. Rembrandt, particularly, had set the standard for charting each rise and fall of his fortunes in a self-image, continuing through the most unflinching confrontations with his flabby features and ebbing vitality in old age. The ageing Picasso apparently felt a strengthening bond with the great Dutchman’s secular materialism, which fostered an earthy realism about all the body’s functions and its weaknesses; but he also found an affinity in Rembrandt’s contrary penchant for lavish costumes and theatrical masquerades” (Kirk Varnedoe, “Picasso’s Self-Portraits,” Picasso and Portraiture, Representation and Transformation, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, 1996, pp. 162-3).

Tables 40, The 347 Series, 1968

| Bloch # | 1481 | 1483 | 1485 | 1486 | 1488 | 1489 | 1492 | 1493 | 1496 | 1497 |

| Beauty | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** | * | * | * |

| Significance | *** | ** | ||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | *** | |||||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | *** | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | ** | ||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bloch # | 1499 | 1502 | 1504 | 1512 | 1520 | 1527 | 1528 | 1529 | 1532 | 1534 |

| Beauty | **** | ** | ** | * | * | ** | * | ** | ** | * |

| Significance | *** | * | ||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | **** | **** | **** | **** | ** | *** | *** | * | *** | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | ||||||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | ** | * | ** | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bloch # | 1535 | 1536 | 1538 | 1541 | 1544 | 1545 | 1551 | 1557 | 1559 | 1560 |

| Beauty | *** | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * | *** | ** |

| Significance | ** | |||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | *** | *** | *** | * | **** | *** | **** | * | * | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | ||||||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bloch # | 1577 | 1590 | 1591 | 1595 | 1599 | 1601 | 1615 | 1623 | 1633 | 1634 |

| Beauty | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Significance | ||||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | **** | ** | ** | **** | * | * | **** | **** | *** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | ||||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | ** | * | * | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bloch # | 1639 | 1646 | 1658 | 1660 | 1661 | 1665 | 1666 | 1674 | 1678 | 1696 |

| Beauty | ** | * | *** | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Significance | ||||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | **** | ** | * | **** | * | * | **** | ** | * | * |

| Visibility at a distance | ||||||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | ** | * | * | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bloch # | 1710 | 1717 | 1719 | 1726 | 1727 | 1738 | 1739 | 1756 | 1758 | 1768 |

| Beauty | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | **** |

| Significance | * | |||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | ** | ** | ** | * | * | * | ** | ** | ** | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | ||||||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | **** | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bloch # | 1769 | 1844 |

| Beauty | ** | * |

| Significance | ||

| Rarity | *** | *** |

| Size | * | * |

| Visibility at a distance | ||

| Color | ||

| Fading | ||

| Cost | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||

| Signature | Y | ES |

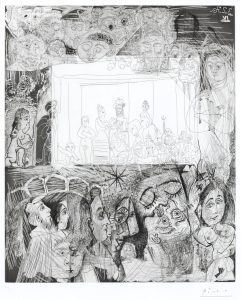

Table 41, The 156 Series, 1970-1972

| Bloch # | 1858 | 1861 | 1862 | 1863 | 1864 | 1865 | 1866 | 1868 | 1869 | 1871 |

| Beauty | ** | * | ** | * | * | **** | * | *** | * | **** |

| Significance | ***** | * | ||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | **** | **** | * | **** | ** | **** | **** | ***** | **** | * |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | * | * | * | * | ** | |||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | **** | *** | ** | ||||||

| Signature | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

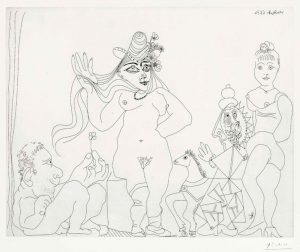

Feuilles (Bloch 1873)

See the discussion of this hilarious and masterful etching, Le Trefle a Quatre Feuilles (The Four-Leafed Clover, Bloch 1873) in its webpage.

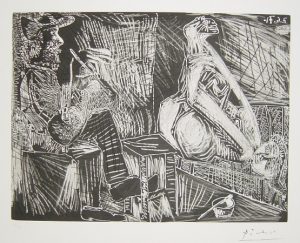

avec sa Toile (B2004)

Table 42, The 156 Series, 1970-1972, cont.

| Bloch # | 1873 | 1876 | 1901 | 1902 | 1904 | 1957 | 1970 | 1972 | 1991 | 2004 |

| Beauty | ***** | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | *** |

| Significance | * | |||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | ***** | **** | ** | ** | *** | **** | **** | **** | **** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | *** | ** | *** | |||||||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ***** | *** | ||||||||

| Signature | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

Table 43. More late Bloch numbers, 1939

(reprinted from Chapter 6)

| Bloch # | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Beauty | * | * | **** |

| Significance | *** | ||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | * | * | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | ** | ** | **** |

| Color | ***** | ||

| Fading | **** | ||

| Cost | * | * | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | ||

| Signature | N | N | N |