What happens when you mix a rare and desirable blue-chip art collection with a bevy of hungry collectors? Well, at the special sale of unique Picasso ceramics from Marina Picasso’s collection, held at Sotheby’s London this June, the result, as you may have expected, was an unmitigated feeding frenzy. Rarely if ever has there been an opportunity for the public to see, much less choose among, such a large collection of the master’s unique ceramics. According to one of the Sotheby’s auctioneers, this assortment represented the lion’s share of Marina’s remaining unique ceramic collection. Even without this disclosure, many collectors must have judged that they were unlikely to ever again come across such a large collection of unique Picasso ceramics.

Casey and I and our three children happily took it all in during our sojourn in London. We of course made a point to scrutinize the several Picasso paintings and drawings on hand, but mostly we wandered about the ceramics room, marveling at the master’s creativity and playfulness and also at the sheer volume of his output (though that last didn’t.

Yet when it came to crunch time, that is, deciding which pieces we would actually like to acquire for ourselves and/or advise our collectors to, the ensuing critical analysis of the collection yielded a strikingly different result than reviewing the collection in its totality. After all, bringing the entire collection home with us was never even remotely the question. Rather, as in any art-buying expedition, the question in its distilled form was, which piece or pieces would we most like to live with?

As I have at times been known to do when beset with a large array of choices (see, for example, my collecting guide for Picasso’s original prints and editioned ceramics), I sharpened my virtual pencil and began the cold calculation of rating Marina’s terracotta treasures. In rating the ceramics, I did not so much compare each piece with others in the same sale as with Picasso’s entire ceramic oeuvre. Comparisons even with his editioned ceramics was warranted, especially in those instances in which there are generally available editioned ceramics of similar appearance, yet at far lower prices. This exercise, perhaps not surprisingly, resulted in a brutal pruning of the many available choices to but a small handful of compelling pieces, price permitting. I went through this process twice, before and after direct inspection of the sale. Direct inspection, as usual, improved the appearance of much of the art. Nevertheless, in the final analysis, only a handful of ceramics remained standing. Using a 0 to 10 scale, only 15 lots achieved better than a rating of 5. These included six 9’s and but two 10’s. Any such schema is of course highly subjective, since it relies on an individual’s own tastes and preferences. And call me a tough grader if you will, but I am prepared as always to defend my point of view.

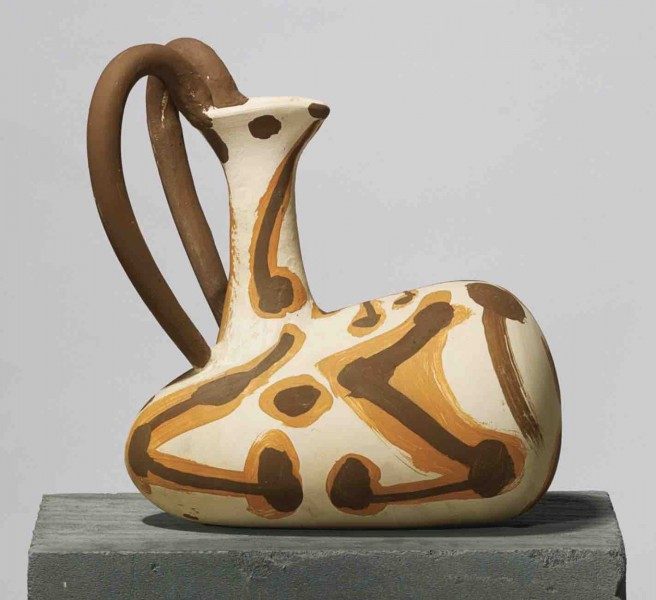

Once the dust had settled, it was clear that Marina’s enthusiasm to rid herself of her estranged grandpa’s art was rivaled only by the enthusiasm of the collectors who snapped it up. Remarkably, all 126 ceramics were sold. Though it took several lots for the bidding to hit its stride, the more coveted pieces soon started selling for 3, 5 and 10 times their pre-auction estimates. Almost everything went high. The lot that soared the highest was a vase of a goat with large handles resembling horns (though it was paradoxically named cabri, French for a kid goat). This 9 in my book fetched £ 485,000 (around $761,000; shown above).

I also loved two clay sculptures. The first of them was reminiscent of his surrealist paintings of the late ‘twenties:

and

There was a fabulous octopus, to my knowledge is a unique subject among Picasso’s ceramics. It soared pretty high, despite an unstable though restorable central crack:

There were some vases with abstract designs (who says Picasso eschewed abstraction?) and also some wonderful tiles and plates depicting owls:

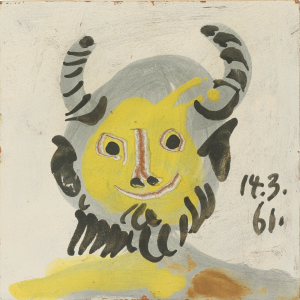

A hilarious faun really had to seen in the flesh to be fully appreciated (at least by me):

In the end, we came away with just exactly nothing (long story, but mostly I had my sights set on a drawing, an aquatint, and a unique ceramic at another auction) and the collectors for whom I had been bidding were too disciplined to have fared any better. It’s not that the achieved prices were too high, at least not for the better pieces. What I was left wondering about, rather, was how many bidders were thinking critically, versus how many were so swept away by the size of the collection, the rarity of the opportunity, and the auctioneers’ hype, as to have momentarily forgotten themselves and bid indiscriminately.

The results sort of speak for themselves. A number of collectors came away with wonderful artworks at not unreasonable prices. Still others ended up the sudden new owners of pricey ceramics of dubious artistic merit. I know of one instance in which the successful bidder had to try to convince himself—after the auction—of the beauty of his acquisition. He succeeded, seemingly. I wonder how many others found themselves in a similar situation. I’m guessing (because, for you psychology buffs out there, of the power of cognitive dissonance) that anyone else who had to try to love his purchase(s) was similarly successful….

The take-home is clear: approach collecting analytically, as well as with the heart. If an auction of interest is approaching, make a firm plan. And before the bidding starts, be sure to get yourself lashed tightly to the mast, safe from the Sirens’ song.