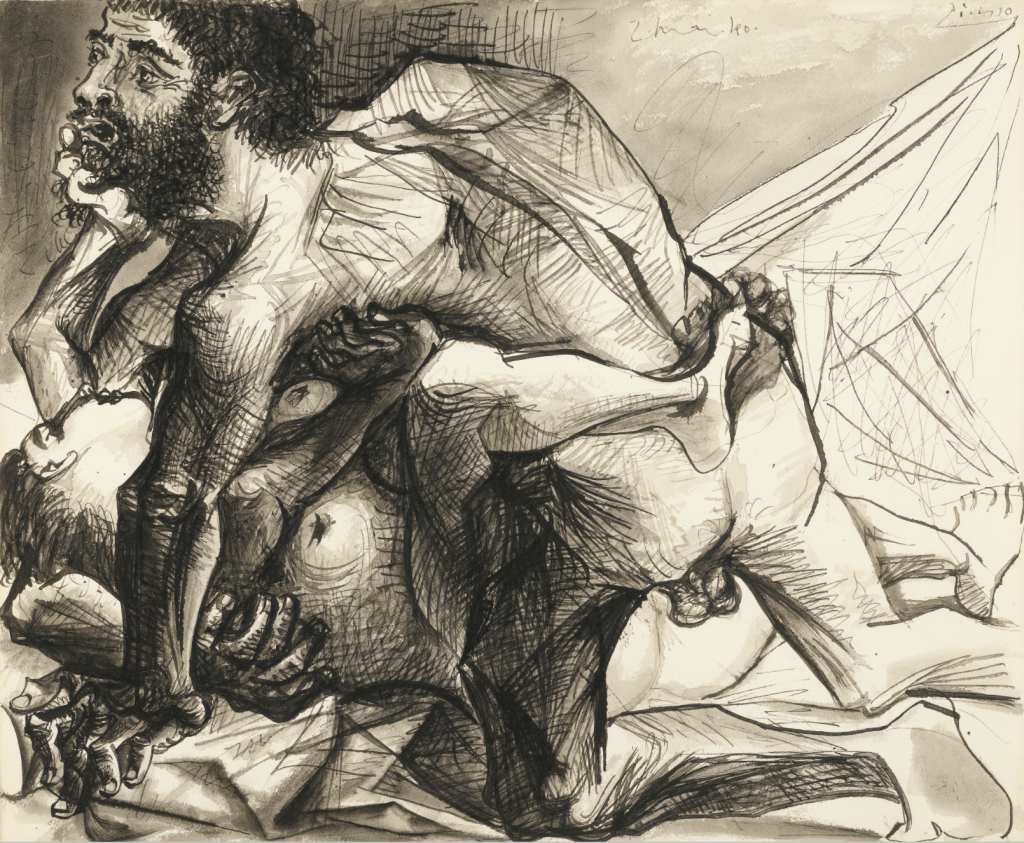

Coupling, I

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: November 2, 1933, Paris

Medium: Etching and drypoint on copper

Dimensions: Print 198 x 279mm, 7 7/8 x 11″; Sheet 340 x 448mm, 13.4 x 17.6″

Signature: Unsigned (By Petiet’s hand, in the lower left margin, “351” is inscribed in pencil.)

References: Suite Vollard 29; Bloch 181; Baer 340 IIBd (the second and final state); OPP.33:040

Edition: From the edition of 260 on Montval paper printed by Lacourière in 1939 before the cancellation of the plate. (There was also an edition of 50 on wider-margined paper that same year.)

Paper: Montval laid; three deckled edges; untrimmed

Watermark: Vollard

Impression: Fine

Condition: The palest toning in the central margins secondary to UV light exposure, with two small, approx. 1 cm areas of tape residue discoloration at the extreme top margin on the back (not showing through to the front); otherwise fine, framed

Price: Upon request

This complex etching and drypoint is one of several masterful Vollard Suite prints which have been variably termed Couple Making Love by Geiser and Baer, Le Viol (The Rape) by Bloch, and The Battle of Love by Bollinger.

The key to interpreting this sub-series is provided by Lisa Florman in her wonderful book, Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso’s Classical Prints of the 1930’s, in the form of many insights about the interconnectedness of the various plates of the Vollard Suite, which she likens to “the intricate mesh of a spider’s web”. Regarding this subgroup of prints, she writes:

At first glance, those plates [of the “Battle of Love”] would seem to have nothing in common with the “Sculptor’s Studio.” Each of the five “Battle” images depicts a couple in the throes of sexual passion: bodies entangled, mouths open—in all, a far cry from the visible quiescence of the “Studio” scenes. But this difference between the two series is not merely difference; it is direct opposition, and it operates on a number of levels. Whereas figures in the “Sculptor’s Studio” are characterized by a certain air of detachment, those in the “Battle of Love” seem anything but detached. By the same token, where vision dominates relations within the “Studio”, the “Lovers” are pressed too close for sight; they shut their eyes tightly or stare without seeing. Although these features are plainly there in the prints, they are brought to the fore only through a comparison of the two series. Those series are, in effect, polar complements, mutually defining each other in their opposition. Confirmation is to be had from plate 28…[Le Viol sous la Fenetre, Bloch 183], the earliest of the Suite’s five “Battle” scenes. In the upper left-hand corner of that image, a window sill and vase of flowers—much as appear throughout the “Studio” series…—are clearly visible. Their inclusion in this plate links the “Battle” with the sculptor’s studio, and thus its frenzied lovers with the studio’s own, more subdued occupants.

As Florman suggests, it is unlikely that Picasso intended to portray the model as an unwilling accomplice to the embrace. For Picasso, the natural progression of sculptor and model from the studio to the bedroom seems much closer to what he must have had in mind.

In 2011, in the midst of their seemingly endless 5-year renovation, the Picasso Museum Paris assembled a traveling exhibit of about 150 paintings, drawings, and sculptures, and generously sent it to various museums around the world. I saw it (9 times no less!) at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. The exhibit was entitled Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris, and it really did include many stunning masterpieces. The exhibit also included a small selection of Picasso’s prints, which a de Young curator told me varied from venue to venue. I can’t speak for the other sites, but the SF exhibit included this powerful artwork, as well as one other Vollard Suite print, the related L’Etreinte, III (B182). The inclusion of these two prints among the large selection of incredible Picasso masterpieces speaks volumes about the quality of these two selections.

I don’t know about you, but I think it compares rather favorably to the following recently sold, almost $14M drawing (at less than 1/2000 of its cost):

The mood between these two artworks is quite different. The drawing is very strong, but it unambiguously depicts a rape and is thus titled. By contrast, the action in the etching is arguably consensual, even rapturous.