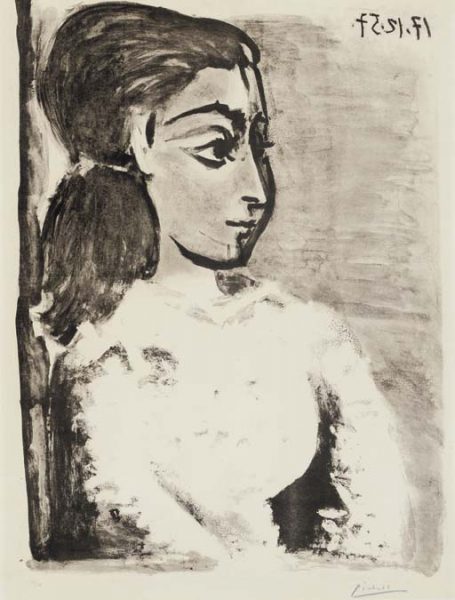

Bust of a Woman in a White Blouse (Jacqueline in Profile)

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: December 17, 1957

Medium: Lithograph with wash drawing and scraper on zinc, lift ground process or direct etching

Dimensions: Print 698 x 514 mm, 27 ½ x 20 ¼”; Sheet 766 x 573 mm, 30 3/16 x 22 1/2″

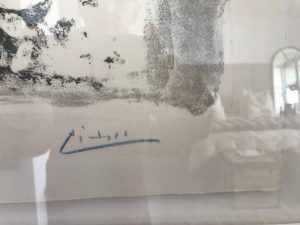

Signature: Signed “Picasso” in thick, navy blue pencil, lower right (see close-up)

References: Bloch 848; Mourlot 311; Rau 666; Cantz 731

Edition: Numbered 21/50, lower left; printed by Mourlot

Paper: Arches wove; untrimmed (deckled edges on the right and left sides)

Watermark: Arches

Impression: Very fine

Condition: Flawless apart from a skillfully repaired one cm tear along the edge of the left margin that is almost invisible, framed

Provenance: Private collection, Australia

Price: Upon request

Picasso first met Jacqueline Roque in 1952 or -3, and he fully installed her into his life after Françoise left him in 1954. Jacqueline became Picasso’s second wife in 1961, and she remained his loyal companion for the last 20 years of his life. As with all his preceding love interests, Jacqueline soon became the primary focus of his art, and eventually her visage, at times faithfully represented and at others—you know Picasso—quite distorted, became omnipresent on the walls and floors of his Provençal villas. By the end, he had portrayed Jacqueline far more often than any other woman in his life.

Picasso’s printmaking however remained faithful to Françoise for another two years after she had left him. Jacqueline first emerged from his limestone the following year with a single guest appearance. Subsequently, Picasso created a handful of lithographs of her, of which this is one. But shortly thereafter he abandoned lithography altogether, after which recognizable depictions of Jacqueline graced his printmaking primarily in his linoleum cuts.

This lithograph, one of the three best of Jacqueline, most tenderly depicts her countenance and, with a few bold brushstrokes, brings out her sensitivity and intelligence so convincingly that the viewer feels he almost knows this woman.

Interestingly, Picasso returned to this same zinc twice over the next twelve months. He presumably was dissatisfied with the appearance of these last two states, because they were not editioned. (Mourlot and Cantz say that the second state was not printed at all, though somehow a photo of it is shown in Cantz. The third state is illustrated in Mourlot.) One must be thankful, therefore, that Picasso saw fit to print the edition of this lithograph before he irrevocably altered it and became dissatisfied with his results. How often one wishes that he had done so with earlier states of other prints, when one or more of those earlier states seem superior to the final, editioned state. In this rare instance, we are grateful that Picasso perceived the beauty of the first outpouring of his vision onto the zinc and memorialized it on paper. Just as this is one of Picasso’s loveliest prints, at almost 70 cm it is one of his largest.