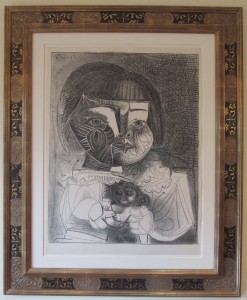

Paloma and her Doll on a Black Background

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: December 14, 1952

Medium: Lithograph (crayon and scraper on zinc)

Dimensions: Image 704 x 550 mm, 27.7 x 21.7″; Sheet 760 x 570 mm, 29 15/16 x 22 7/16″

References: Bloch 727; Mourlot 229; Hatje Cantz 614 (also illustrated on the back cover); Rau 563

Edition: Numbered 5/6 on verso, one of 6 proofs outside the numbered and signed edition of 50 (Mourlot records 5 artist’s proofs and one printer’s proof); printed by Fernand Mourlot

Signature + Inscriptions: On the verso, inscribed bottom right “5/6” and signed “fm” (the printer’s initials) as well as with the inventory number, and “229” (the Mourlot catalogue reference number) bottom left

Paper: Arches wove; untrimmed: deckled edges on all sides, most pronounced on the right and left sides

Watermark: Arches

Impression: An unusually rich, deep impression

Condition: Flawless

Price: Upon request

As John Richardson’s saw it, “Picasso’s Mediterranean happiness was enhanced by the birth of a son, Claude, in 1947, and a daughter called Paloma in 1949. The proud father was 68 when Paloma was born. I think the fact that Picasso hadn’t had a child in his life for 30 years made a huge difference, and having these young children, being by the sea, this spirit is reflected in all the works of Françoise and that period.” (Picasso: Magic, Sex, Death, lectures on DVD, 2003)

Picasso’s exuberance for his second daughter is no better captured than in this wonderful portrait of Paloma playing with her doll, by far the finest portrait of Paloma in all of Picasso’s printed works and certainly one of Picasso’s very best prints. Paloma, with her chubby cheeks rendered in a beautiful, complex, inimitable, iconic Picasso style–a latter-day Cubist riff, really–is clutching a doll in her stubby fingers. This portrait of Paloma’s face is nothing short of a miracle, complemented by the remainder of the composition, most memorably her frilly collar and puffy sleeves. Her doll’s face is fantastic, too, especially in that its Baroque yet Picassian style is in stark contrast to Paloma’s more Cubist depiction. Then there are Paloma’s hands. Picasso, known of course for his boundlessly imaginative and endlessly varied hands, here invents yet another iteration of this lifelong creative focus. In Japanese art, unlike the Western canon, the face is accorded no more emphasis, that is, no more definition or detail, than the rest of the body. Though Picasso is and should be known for his depictions of the entire body, clearly one thinks of the face as his primary creative focus, and especially the eyes. Volumes could be written just on his eyes. But the hands were next in line.

Her jokester father was always planting humor in his art, from obvious to veiled. In the juxtaposition of daughter and doll, he amusingly inverted reality by rendering the doll more realistically than the child. The doll would have been inspired by the cruder wooden ones that Picasso made for his daughter, delightful creations that he carved with his own hands. But in this lithograph as well as in its companion lithograph created the same day, “Paloma et sa poupée, fond blanc” (Bloch 726), Picasso left no hint that the doll is wooden. Unlike the doll in the lithographs, the wooden dolls’ faces were all portraits of Paloma:

The problem is that all of the seven known wooden dolls are dated 1953. Well, they could have been misdated, or he could have presaged their creation in the lithographs, which would have been typical of this creative genius.

*****

The unusually rich impression of the Paloma at hand is best demonstrated in this side-by-side comparison: