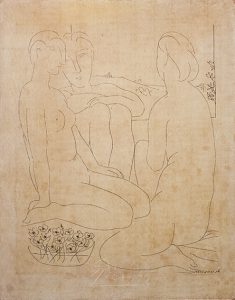

(Please pardon the assault on your eyes by the above ugly fake.)

Just about every day an email arrives inquiring about the authenticity of their artwork. Often the writer is seeking confirmation that what they have is an actual Picasso. Just as often they’re sure of authenticity but are just seeking valuation or a sale. I’d say at least 90% of the time, the object in question is a fake or forgery. Usually the sender is grateful for whatever information I’ve provided, but sometimes it doesn’t go so well. Like this instance, regarding several photographs, one of which is illustrated above:

Q: Can I please get your input on these Picasso drawings. I appreciate your time and reply.

A: In my opinion, they are all fakes.

Q: Really , that doesn’t sound like an expert opinion . have you really taken a close look .Never bloody mind . Dingle berry [sic]

Sigh. I try to answer all my email, but often it’s hard to know my correspondent’s motives in advance: are they interested in the truth, or do they already know it’s worthless and are just out to swindle. Often it’s hard to tell from a single email whether you’re a crook or just uninformed (or both). I especially dislike wasting time on crooks. In an effort to cut down my email volume, I’ll provide this DIY guide to authenticating your own Picasso, if you please. Because time is limited and, try as I may to steel my emotions, some of the responses to my opinions rather rankle.

As a case in point, I’ll pick the 100 prints that comprise the Vollard Suite (VS for short, or simply Vollard). The reasons for this choice are twofold: Vollards are often faked or forged, and, whereas the rules for authentication vary from medium to medium and artwork to artwork, the rules for all the VS prints are much the same. So I can hopefully obviate most of your questions, at least about 100 specific Picassos, in one fell swoop.

Here I’ll stick to the “regular” edition of 260 and the “deluxe”, wide-margined edition of 50. That will cover almost all the impressions, leaving out just the 3 proofs on parchment and the other hyper-rare proofs which details could be looked up in Volume II of Geiser/Baer. Note that other than the sheet sizes and the watermarks, impressions from the regular and deluxe editions are essentially identical. One other respect in which these two editions vary is that, with rare exceptions, Picasso signed the entire deluxe editions, whereas he signed the entire regular editions of but a dozen of his favorite Vollards. (The photo on top is obviously not a Vollard. I included it just because it accompanied the insult I last received.)

I’ve already broached these issues more generally in the authenticity section of Chapter 13 entitled “Collecting Pitfalls” in A GUIDE TO COLLECTING PICASSO’S ORIGINAL PRINTS, but now we’ll get down to the nitty gritty. Here we’ll be examining the rules for the authentication of the prints themselves, not their signatures. The determination of authentic signatures is a whole other story, which I won’t address here but which I covered in more general terms in Chapter 12, entitled “Is It Signed?”. Since for most VS prints, Picasso signed but a fraction of each edition, there are many cases of real VS impressions which nonetheless bear forged signatures. Though, as it has been said, eventually all the VS will be signed.

Bear in mind that the vast majority of inauthentic Vollards are photoreproductions of one type or another, rather than images that were drawn or etched freehand. These repros have no significant value. A common example is the so-called German VS “edition”, which is, one reads, a set of VS lithographs. But they are not lithographs made by Picasso; rather, at best, they are lithographic photoreproductions of the VS prints. At worst, VS repros are just pages torn out of coffee table books. There is not much difference in value between these best and worst case scenarios. (For more on the German “edition”, see my prior post entitled “Anatomy of an Art Fraud on eBay”.)

So here goes. There are a number of rungs that your Vollard must surmount in order to pass muster, as follows, starting with the simplest:

1. Sheet size. Provided that nothing else jumps out at you that outs the piece at hand, the easiest determinant of authenticity is size: the size of the image and the size of the sheet. The sheets have upon occasion been trimmed to eliminate damaged edges, so the proper sheet sizes represent the maximums. (Of course the more a sheet has been trimmed, the more the value has been commensurately trimmed.) The sheets on which the VS was printed were handmade and therefore vary a bit in size. The size (to the platemarks) of the images themselves vary slightly from impression to impression, and the overall sheet size varies a bit more. You can look up the platemark size in any catalogue raisonné of Picasso prints (typically Bloch), and you can usually find the sheet sizes online in various reputable sources. I can save you the latter step by noting the approximate range of sheet sizes, as follows. For the regular edition of 260, the range of sheet measurements are about 446 ±4 mm x 338 ±5 mm. For the deluxe edition, the sheet size is approximately 502 x 389 ± 5 mm.

2. Platemark. The indentation around the perimeter of the image can be simulated by a forger, but if it’s absent, it means the print is either wrong or the sheet has been immersed for cleaning without care to preserve the platemark.

3. Paper. Both editions of 260 and 50 were printed on laid paper, a descriptive term for one of the ways hand-made paper is produced. Laid paper is identified through transillumination, which reveals parallel lines throughout the sheet that are spaced about 2 cm apart. These lines transmit more light and thus appear brighter than the remainder of the sheet.

4. Petiet stamp. In recent years the Petiet estate created an ink stamp that they applied on the verso of the unsigned impressions left in their collection. The presence of this stamp indicates that Picasso didn’t sign that impression. Today however, most of the forged signatures on real VS impressions pre-dated the deployment of this stamp.

5. Deckled edges. The sheets for both editions were produced by quartering a larger, parent sheet. This larger sheet had deckled edges circumferentially, so its resultant quarters have two deckled edges, provided that the sheet has not been trimmed.

6. Inventory numbers. In both editions, there is often a penciled three-digit number in the corner of the lower left margin, which are presumably Petiet’s (or Vollard’s) inventory numbers. They don’t adversely affect valuation and no one even mentions them when describing the condition of a print or, if they do, not as a flaw. They don’t exactly add to the value, either. These inscriptions may support authenticity, though the determination of authenticity typically rests on other much more important criteria. Of course the numbers should be written in the French style, e.g. the sevens should be crossed.

7. Watermark. Every impression from the regular edition has a watermark, best scrutinized through transillumination. Half of the impressions of the 260 edition bear a “Picasso” watermark, the other half have a “Vollard” watermark. They look like this:

I have not seen an example of a forged Vollard watermark, but I have seen forged Picasso watermarks. One looked like this:

The edition of 50 may or may not have a watermark. Just as for the edition of 260, the sheets that were used for the deluxe edition were made by quartering a larger sheet. But unlike the regular edition, there were only two watermarks on the original, larger sheet, so half the impressions of the deluxe editions bear a watermark and the other half have none. One of the two watermarks on the deluxe sheets represents the paper manufacturer, and consists of a circle, within which the letter “M” is superimposed over the letter “V” for Papeterie Montgolfier à Montval. I presume those letters stand for the M and V in Montval. The other watermark is named Galatea and depicts a woman holding a scarf above her head, a motif that the papermaker had adapted from a work by Aristide Maillol. (I have not seen forged Montgolfier or Galatea watermarks.) As I recall, each of the four watermarks measures approximately 2.5 cm in greatest diameter.

8. Edition number. Neither edition was numbered. So if it bears an edition number, unless it’s one of those hyper-rarities that is numbered in red pen to 3 on parchment or to 15 on laid paper, it’s bad.

9. Fine lines. If your print has passed all the preceding tests, this final test demands a bit of scrutiny, while you compare your piece to a known reference impression, ideally an original though a high-rez photo of an original will usually do. There is a limit to how true the photoreproductive processes are to the original artwork. I’ve covered this in a prior blogpost regarding a linocut [insert hyperlink to B908 blogpost], but the principles are the same for the VS, so I won’t repeat them here.

By contrast, authenticating Picasso drawings and especially paintings is typically much harder than this, but that’s a whole other story. This is it for now. As you can see, outing fakes and forgeries is not rocket science, far from it. Armed with these tips, you can now start sleuthing! When you or I do our jobs well, there is no room left for doubt.

Super helpful post and I just wish I’d come across this page before getting excited about a fake Vollard with a signature and stamp (but wrong size and no watermark). Another telltale is the price and lack of documentation (provenance) and of course staying clear of sites like eBay which must be responsible for majority of fakes. Thank you!