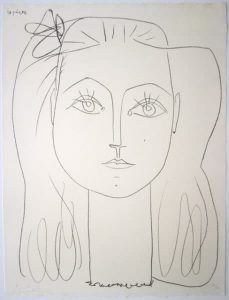

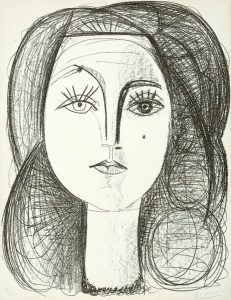

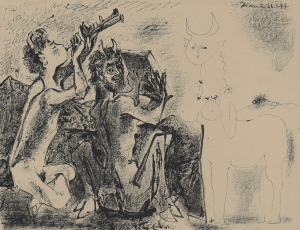

les Cheveux (Bloch 397)

Despite wartime privations, Picasso began creating lithographs in earnest in 1945. Although their subjects varied, their star was Françoise Gilot, whom he had met two years before. In these early lithographs of his new muse, he famously applied a very spare line, but one nonetheless laden with greatly evocative emotion.

Some of these eight portraits of Françoise which Picasso created on the same day (Bloch 396-403) are among his finest lithographs. See a discussion of Françoise au nœud dans les cheveux (Françoise with a Bow in Her Hair, Fig. 27) in its webpage in our catalogue.

Table 16. Lithographs 1945-1946, Mostly Françoise

| Bloch # | 378 | 379 | 380 | 383 | 384 | 388 | 389 | 390 | 395 | 396 |

| Beauty | ** | * | *** | **** | *** | * | **** | * | **** | ***** |

| Significance | *** | *** | *** | * | **** | *** | *** | ***** | ||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Size | ** | *** | *** | ** | ** | **** | ** | ** | **** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | *** | *** | **** | *** | *** | ** | ** | * | ***** | **** |

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | ** | ** | * | * | * | * | * | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | ** | *** | **** | ||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

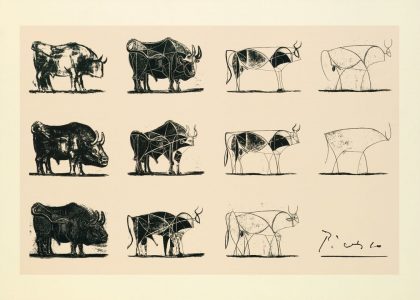

Sometimes, eleven pictures are worth a thousand words:

on stone), 11 states, 1946

Table 17A. Lithographs 1946-1947, Françoise and Owls

| Bloch # | 397 | 398 | 399 | 400 | 401 | 402 | 403 | 404 | 408 | 409 |

| Beauty | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** | ***** | *** | * | *** |

| Significance | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** | ***** | *** | * | *** |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | **** |

| Size | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | **** | **** | ***** | ***** | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** | **** | ***** |

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | * | ** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

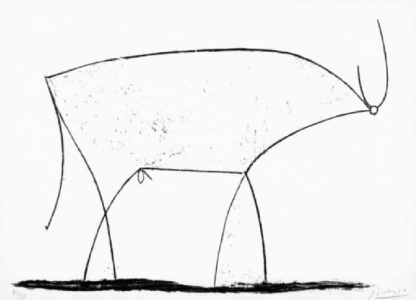

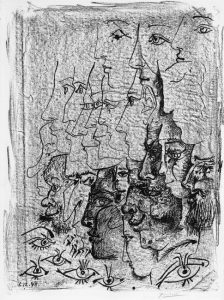

Centauresse (Bloch 413)

Table 17B. Lithographs 1946-1947, continued

| Bloch # | 410 | 411 | 412 | 413 | 423 | 435 | 438 |

| Beauty | *** | *** | ** | ***** | **** | ** | ** |

| Significance | *** | *** | *** | **** | **** | *** | ** |

| Rarity | **** | **** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | *** | *** | **** | ***** | **** | *** |

| Color | |||||||

| Fading | |||||||

| Cost | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | |||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

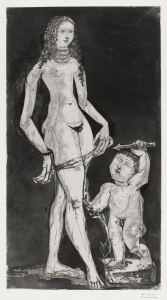

(Bloch 581)

For a discussion of this lithograph (Fig. 29a), please see its webpage in our catalogue.

Table 18. Assorted media, 1947-1948

| Bloch # | 442 | 455 | 456 | 457 | 458 | 461 | 463 | 467 | 577 | 581 |

| Beauty | * | * | ** | *** | * | * | * | * | ** | *** |

| Significance | *** | * | *** | |||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Size | ***** | ***** | **** | ***** | **** | ** | ** | ** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** | ***** | * | * | *** | *** | |

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | *** | *** | ** | *** | ** | * | * | * | ** | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

Table 19. Lithographs, 1949

| Bloch # | 583 | 586 | 587 | 588 | 589 | 594 | 595 | 596 | 597 | 600 | 601 | 602 |

| Beauty | ** | **** | **** | **** | *** | * | **** | **** | ** | * | *** | **** |

| Significance | *** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ** | * | **** | **** | **** | * | ** | **** |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | **** | |

| Size | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** | **** | |

| Color | ||||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||||

| Cost | *** | **** | **** | **** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | *** | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | |||||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

Table 20. 1949-1950

| Bloch # | 603 | 604 | 611 | 612 | 613 | 614 | 1835 | 615-28 | 1836 | 664 | 675 | 681 |

| Beauty | **** | **** | * | ** | **** | ** | ***** | *** | * | ***** | ***** | * |

| Significance | **** | ***** | **** | **** | ** | ***** | *** | **** | **** | ** | ||

| Rarity | **** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Size | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | *** | **** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** | ** | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** |

| Color | * | ***** | **** | |||||||||

| Fading | * | ***** | ***** | |||||||||

| Cost | *** | **** | * | **** | ** | ** | **** | **/set | ** | * | *** | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | * | * | ***** | * | |||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ES | N | P | N | Y | Y |

Venus et l’Amour (Venus and Cupid; Bloch 1835, Fig. 29) is one of Picasso’s greatest prints in general and one of his top five masterpieces in aquatint, as I count them, largely in agreement with Picasso connoisseurship and the marketplace. Not counting La Femme qui Pleure, I (Bloch 1333), since it is mostly an etching, the other four are, in chronological order: Minotaure Aveugle guidé par une Fillete dans la Nuit (1934, Bloch 225), La Femme au Tambourine (1938, Bloch 310), La Femme à la Fênetre (1952, Bloch 695), and L’Egyptienne (1953, Bloch 746). After the last two mentioned, the Venus is also the third largest intaglio print on copper or zinc, or, in other words, his etchings and aquatints. The story of this masterpiece is best told by Brigitte Baer, from whose monograph Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection (1983) I quote liberally:

The Galerie Louise Leiris edited this print at the same time they edited the group known as ‘the 156 prints’, although there are only 155, a small copperplate having been somehow mislaid. The artist approved the bon a tirer proofs before he died. The edition was put on the market in 1979….

The copperplate is not inscribed on the back, as are most of the others; thus it is difficult to be more precise about the date. In 1949, Picasso made three lithographs of the same subject…. The quality of the print on exhibition [this print] is much finer than that of the lithographs. The first state is done only with aquatint. As the plate was so large, it would not fit in Lacourière’s dusting-box and so was difficult to grain…. Picasso must have begun the plate around May 1949. It seems probable that he then thought of having it printed, since a small number of proofs were pulled. Then, maybe in the middle of the printing process, he decided to continue working on the plate. He took the trouble to blot out, with drypoint, all the white spots left in the aquatint of the background. Over and again, Venus gets fatter, then thinner, fatter, then thinner. Her arm, on the left of the proof, swells, as if it had been stung by a squadron of wasps, then shrinks again. The artist could not capture the graceful posture he sought, the other arm was too close to the body, the hair was too long, etc. so Picasso worked and reworked the plate at Lacourière’s. Frelaut printed and reprinted the trial proofs until the masterpiece was achieved….

For a discussion of this finger-painting lithograph, Paloma et Claude (Bloch 664, Fig. 30), please see its webpage in our catalogue.

Table 21A. 1951-1952

| Bloch # | 684 | 685 | 686 | 687 | 691 | 694 | 695 | 696 | 697 | 713 |

| Beauty | *** | *** | * | **** | **** | * | ***** | ***** | *** | ** |

| Significance | ** | ** | * | **** | *** | ***** | **** | *** | ** | |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Size | *** | **** | **** | ** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | * | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | ** | *** | *** | **** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ** | |

| Color | * | |||||||||

| Fading | * | |||||||||

| Cost | * | * | ** | * | * | ** | ** | * | * | |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | * | *** | **** | *** | ** | ||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y/N | ES |

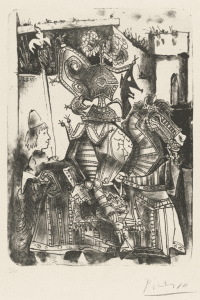

le Page (Bloch 684)

In 1951, both before and after the monumental but somber anti-war painting, Massacre in Korea, Picasso also treated the subject of violent conflict in a lighter vein. Having apparently become nostalgic for the pomp and circumstance of chivalry, he created a number of paintings, unique ceramics, and prints with charming scenes of knights in armor. Two examples are pictured: the lithograph Le Chevalier et le Page (The Knight and the Page, Fig. 31, Bloch 684), and the related as shown, which resides in the Musée Picasso. Look closer, however, at these works, and you will see the ridiculously elaborate armature of the knight and horse—a mask behind a mask, silly helmet plumage—this dog would certainly not hunt. Picasso was an incisive political commentator to be sure, but, as during the Second World War, he could not stay despondent about the state of world affairs for long. Sooner or later, humor always infected his commentary.

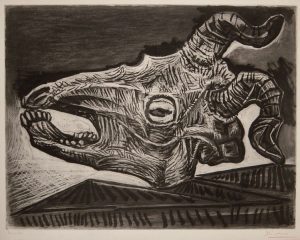

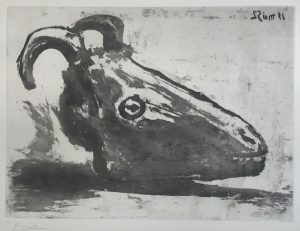

sur la Table (Bloch 696)

For a discussion of this aquatint, Le Crâne du Chèvre sur la Table (Bloch 696, Fig. 32), please see its webpage in our catalogue.

And for this discussion, see this webpage in our catalogue.

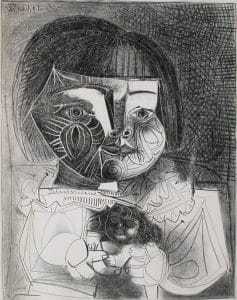

Poupée, Fond Noir (B727)

Please refer to its webpage for the discussion of this masterpiece, Paloma et sa

Poupée, Fond Noir (B727).

Table 21B. 1952-1953

| Bloch # | 714 | 715-22 | 723 | 724 | 725 | 726 | 727 | 728 | 731 | 733 |

| Beauty | **** | **** | *** | * | **** | ***** | ***** | *** | ** | * |

| Significance | ** | ** | ** | * | ** | **** | ***** | ** | * | * |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Size | * | * | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ***** | *** | **** | * |

| Color | * | * | ||||||||

| Fading | * | * | ||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | ** | *** | * | ** | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | **** | **** | *** | **** | ** | ** | *** | |||

| Signature | P | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

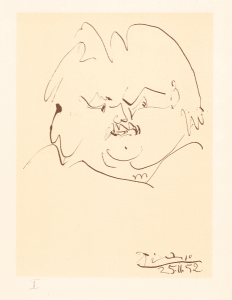

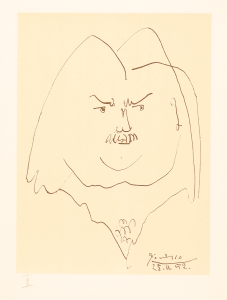

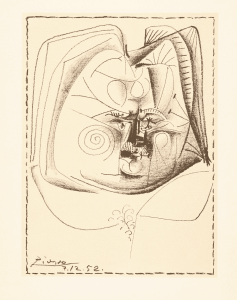

Fig. 34. Balzac (from the series Bloch 715-722)

Picasso once said, ” The movement of my thought interests me more than the thought itself.” (See the discussion in Chapter 2.) A classic example of the flow of Picasso’s creative juices captured on paper is this series of nine wonderfully amusing lithographs of Balzac, eight of which were published in this elegant folio (Bloch numbers 715 through 722). The unusual aspect of this series is that it is otherwise generally impossible to purchase a large group of Picasso’s consecutive riffs on a single theme, especially for a rather affordable price (in the very low five figures, that is; these prints are also individually available for around $2000-3000 a pop). Most of Picasso’s variations took the form of successive states of the same print. But once he reworked the stone or plate, these variations were lost forever, apart from the one, two or three artist’s proofs that were typically pulled of each state. These are usually in museums, are otherwise very hard to find, and are generally pricey.

Balzac’s imposing physiognomy must have been artistically compelling. Rodin fell prey to it, and Picasso clearly could not escape its charm. This set of eight lithographs presents a superior example of the easy marriage Picasso had arranged between fine art and caricature. It also displays a charming graphic progression of alternately diminishing and increasing complexity as Picasso plays with different ways of rendering the novelist’s face. First he toys with Balzac’s coiffure and brow. Then he adds some gravity to Balzac’s expression. Next he strips away as much detail as he can while still retaining the essence of “Balzacness”. In the last two images, Picasso rebuilds the face with his signature stylizations, now playing the opposite game of how many of them the face could juggle while yet retaining its essential nature. Each portrait of Balzac is marvelous in and of itself, but the set when viewed as a whole is even more riveting than the sum of its parts. It is a truly rare experience to behold at once the consecutive results of the artist’s creativity, but this series offers no less than just that.

Here’s how these gems came to be. As Mourlot relates, “Picasso arrived in Paris for a few days and I asked him to do a portrait of Balzac for the publisher Sauret…. The following morning….Picasso handed me 8 litho drawings….numbered from I to VIII as well as three large compositions. A few days later, he re-worked a crayon litho [unnumbered by Picasso, Bloch 722]….of the same subject.” The lithograph numbered II was chosen as the frontispiece for Sauret’s publication of Balzac’s Le Pere Goriot, and the remaining eight were later published in the book presented here.

Those who have seen any of the three large lithographs of Balzac and found them wanting because of their unsaturated, faint black line may be pleasantly surprised to behold these eight smaller lithographs. Despite their size, they pack a more powerful punch because of the fully saturated, deep black line with which they were inked, not to mention their rich, yellow background, a not inconsequential bonus for all the color-starved Picasso lovers out there.

Table 22. 1953

| Bloch # | 735 | 736 | 737 | 738 | 739 | 740 | 741 | 742 | 745 | 746 |

| Beauty | * | * | *** | ** | ** | *** | ** | *** | *** | ***** |

| Significance | ** | * | * | *** | * | ** | * | ***** | ||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** |

| Size | ** | ** | ** | *** | ***** | **** | ***** | ***** | ** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | * | **** | ***** | ***** | **** | **** | ** | ***** | ||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | ** | * | ** | *** | *** | *** | * | ***** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | * | * | |||||||

| Signature | ES | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/Y | Y |

Torse de Femme (aka L’Egyptienne, Bloch 746) is one of Picasso’s best prints and also one of his two largest prints on copper. One of the printers in Lacourière’s studio dubbed it The Egyptian Woman as it first came out of the printing press, and the nickname stuck. I’ve given this work five stars in the Blushing Flowers category because I was never that impressed by photoreproductions of it in textbooks, until I finally saw it “in the flesh”, at which point I became utterly transfixed by its beauty. This may be an idiosyncratic reaction, however, (as may all of my Blushing Flower designations) given the fact that I have sold an impression of this print to a collector who first became enamored of it while looking at its image on our website.

Table 23. 1953-1954

| Bloch # | 747 | 749 | 750 | 751 | 752 | 753 | 754 | 755 | 756 | 757 |

| Beauty | *** | ** | * | * | **** | **** | * | * | **** | * |

| Significance | * | * | ** | ** | *** | *** | ** | ** | *** | |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | ** | ** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ||

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * |

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | * | ** | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | * | ** | ** | ||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

(Bloch 753)

For a discussion of this lithograph, La Danse des Banderilles (Bloch 753), please refer to its webpage in our catalogue.

Saltimbanque (Bloch 753)

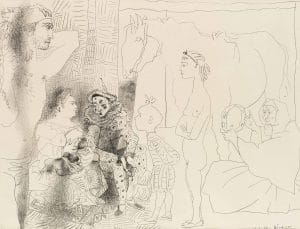

This lithograph also harkens back to the circus theme which had figured prominently in Picasso’s early work. La Famille du Saltimbanque (Fig 36a.) has all the important elements: the horse, the nude equestrienne (albeit with Françoise’s visage), the harlequin, the acrobat with his monkey, the mother of the family, and the grandmother. The grandmother perhaps evokes the brothel’s madame, another archetype which haunted Picasso’s work, especially near the beginning of his career and again near the end of his life. One of the subtexts in the social commentary of this print, the black baby born of a white mother, is unique in Picasso’s print oeuvre. The young boy looking inquisitively at the family scene is, we imagine, the older Picasso himself, traveling back in time, bald except for a sprig of hair at the top of his head.

Table 24. 1954-1955

| Bloch # | 758 | 764 | 765 | 768 | 769 | 770 | 771 | 772 | 776 | 777 |

| Beauty | * | * | ** | * | * | ** | *** | * | * | |

| Significance | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | ***** | **** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ** | ** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | * | **** | **** | **** | **** | ** | ||||

| Color | *** | *** | ||||||||

| Fading | *** | ***** | ||||||||

| Cost | * | * | ** | *** | *** | ** | ** | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ES | ES | ES |