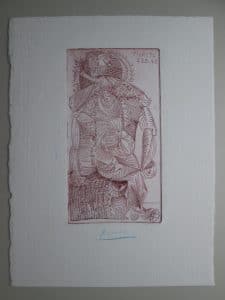

Seated Woman (Frontispiece for Contrée)

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: 1943

Medium: Etching on copper printed in deep red

Dimensions: Print 245 x 131mm, 9 5/8 x 5 3/16″; sheet 377 x 286 mm; 14 7/8 x 11 1/4″

Signature: Signed in bright royal blue pencil at bottom; signed and dated in the plate

References: Bloch 362; Baer 689Bb; Cramer 39;

Elliott, Picasso on Paper, National Galleries of Scotland, 2007, illustrated p.84

Unique Printing: A unique, unrecorded impression, the only impression printed in dark red, one of only several hand-signed, even fewer signed in blue pencil, and one of the only impressions on an oversized sheet (I know of one other trial proof printed on Japon that is also oversized)

Paper: A handmade, unusually heavy (200 or 300 lb. weight), hyper-absorbent Winsor & Newton watercolor paper, almost 1mm in thickness, with deckled edges on 3 sides, and with deeply impressed platemarks. This heavy watercolor paper, intended to best absorb watercolor, is apparently also more absorbent of the printer’s ink than the other types of paper that Picasso more typically used.

Watermark: Winsor & Newton winged lion, to the left of the subject

Impression: Exceptional, with plate tone throughout, especially at the top, like a cloud above the subject. (There is no plate tone in the regular edition, at least not in the multiple impressions that I’ve seen.)

Condition: Excellent

Price: Upon request

In addition to the unsigned regular edition, Baer and Goeppert/Cramer mention ten deluxe sets of books, each of which contains a set of four etchings, printed in blue, green, and orange in addition to the standard black:

Picasso signed each of these ten books in blue pencil on the justification page, but not on the prints themselves. This is an interesting set, but, apart from the black, the other colors he chose are rather light, especially the green and orange, reducing the contrast and hence the visibility of the art. Not so with the striking impression at hand.

Nor does Baer note any other impression that is printed on an oversized sheet or that is hand-signed in blue on the sheet itself. (Baer records four trial proofs (“epreuves d’essai”) printed in black on four different papers, different from ours, but doesn’t mention the presence or absence of signatures upon them. One of these four prints, thusly annotated in black ink and bearing a black ink signature, was auctioned in Paris in 2012, fetching 13,000 euro, despite rather extensive foxing. Another is in the collection of the Picasso Museum Barcelona. A third, unsigned impression on oversized Japon, is in the private collection of a friend of mine.

Judging by the paintings and drawings of this period, this remarkable etching represents Dora Maar. Of Picasso’s three mistresses at the time, Dora was on the wane. In the words of John Richardson, one of Picasso’s premier biographers, “Picasso’s art always reflects the circumstances of his life, and we can watch the deterioration of his relationship with Dora in the exceedingly troubling portraits of her.” (Picasso: Magic, Sex, Death, lectures on DVD, 2003) But this portrait is much more than a commentary on Dora Maar. This fireplug of a woman is as much a commentary on the raging war, in keeping with the text of the book for which it served as the frontispiece (see below), as it is a reflection of his attitude toward Dora. With her full-body armor and limbs swinging on mechanical joints, she is a feminine effigy in the guise of a battle tank.

In this portrait, Picasso seems to have conflated her visage with his beloved Afghan hound’s snout. Goeppert and Cramer write that this etching likely represents an embracing couple. It however is clear to me that, apart from the extraneous snout, a single woman is depicted, simultaneously from the front and back, in yet another novel iteration of Picasso’s cubist-surrealist styles. This figure is afforded sculptural volume by the many fine linear flourishes with which he endowed her unique anatomy.

This has always been one of my all-time favorite Picasso prints. I have never been apart from her (apart from vacations) since the early eighties, and therefore endeavor to acquire additional impressions to share with you. Perhaps because this is a relatively small etching and one not readily visible from across the room, or perhaps because she is not for everybody, this masterwork is one of the most undervalued Picasso prints.

This portrait graced a book of poems written by Picasso’s friend, Robert Desnos. The year of publication was wartime, and the poetry was a call to arms. The final poem included the prophetic statement, “Vivants, ne craignez rien de moi, car je suis mort (Have no fear of me, living ones, for I am dead)”, for the Gestapo arrested Desnos for his involvement in the French Resistance, just before the publication of the book. He died 15 months later in captivity at the Nazi concentration camp Terezin. Timothy Adès, who has translated the poems (see http://www.bcla.org/tc2002/ades.htm ), has provided the following comments:

Contrée (in print from May 31, 1944) appeared a month after Desnos had left the Royallieu camp at Compiègne [for Auschwitz; from there he was marched to Buchenwald, Flossenburg, and Flöha, where he worked as a slave labourer making aircraft parts; he died at Terezin]; so the poet never saw the collection in print. Contrée was published … at a time when Desnos often talked to Picasso, and was writing about him…. The title Contrée denotes both the various places visited in each poem (because it can mean something like Back Country) and the effect of ‘countering’, more or less by stealth, an enemy whose defeat is proclaimed: ‘I have wished your death and there is nothing that can delay it.’ The allusions multiply. Here is denunciation: ‘on a yellow poster the word in black letters, plague;’ the voice declaring ‘the beautiful season is near;’ and the poet’s anticipatory epitaph, his refusal to give in: ‘I lived intact, but I was prey.’ Classic in form, and drawing on mythology, the poems were able to pass the censor; and their philosophy of human destiny puts into a wider context various topical allusions which those in the know could understand.

The first of the poems, with translation by Adès, reads as follows:

THE WATERFALL

What arrow split the sky and pierced the rock?

Vibrant, it spreads its peacock tail and flaunts

Its blurry shaft and sleek unblemished flights,

The way the midnight comet finds its mark.

The flesh is opened. For the blood to rise,

While lips suppress the murmurs and the cries,

A finger bids time stop, pre-occupies

The witness who records it with his eyes.

Silence? And yet we know the passwords well.

We strayed from our camp-fires, we sentinels:

Drifting from shady corners we can smell

Salt surf aromas, honeysuckle smells.

Dawn bursts on far-off depths; a sunbeam limns

Upon the waves, at last, a sketch that leads

Back the returning archer and his hymns:

A rainbow, with its quiver full of reeds.

I recently received a fascinating and revelatory discussion of the meaning of this etching, as follows. (Note: The author of this discussion refers to the illustrations, which were included in the book of poetry in which this etching was published, as “fragmented tailpieces”, because each illustration consists of a different fragment of the etching reproduced at the bottom of some of the pages.)

As you know the fragmented tailpieces at the bottom of Desnos’ poems in the book are derivatives of the etching you have, thus making the poems, the etching and the tailpieces a single integrated artwork. Together they comprise a good example of the use of the illustrated book as a strategic instrument in the cultural battle that raged in France during the Nazi occupation.

Observe the first tailpiece, the decapitated head of Maar. The decapitated head was an resistance symbol for the brutality of the German occupiers. You would know that Picasso also used the decapitated head, including the detached Medusa head, in his over sketching of a single copy of his Buffon, Histoire Naturelle, as a gift for Dora Maar. (Jonquières published a facsimile of this book in 1957). The detached head represented Picasso’s fears at the time.

Observe the final fragment in Contrée, the ‘books’. He used the ‘books’ fragment three times, the highest use of this fragment. It was Picasso’s coded message that the ‘word’ will eventually triumph. A coded ‘pen is mightier than the sword’.

Picasso was well aware of the danger the Maar etching and his fragments posed. In fear for his safety after Desnos was arrested by the Gestapo, since the book had yet not been published, Picasso demanded that his etching be withdrawn. It was Youki’s (Desnos wife) plea that presumably changed Picasso’s mind. As you point out in your website, unfortunately Desnos died in a prison camp just four days after the Allied and US troops landed at Normandy to begin the liberation of France. Desnos never saw the book.

Although Desnos poetry has received extensive analysis, the fragments have not. My PhD thesis provides an analysis of these fragments, within the context of the use of decapitated body in resistance-based artists books…. I just handed my thesis in and am embarking on a new journey, to buy as many of the illustrated books that I have referenced as is possible. – Rodney S., Australia, 2015