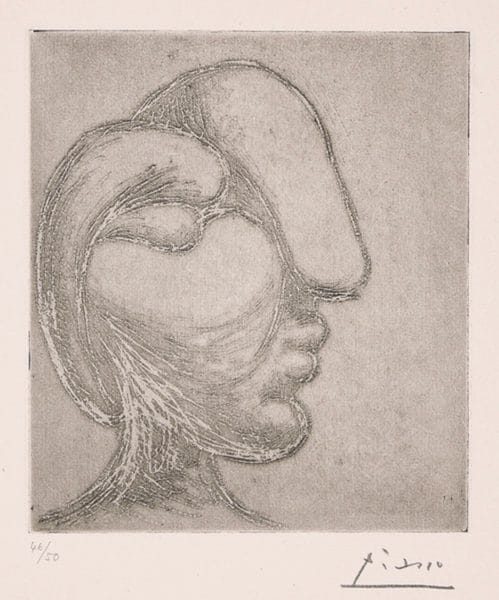

Head of a Woman

Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Date: 1933

Medium: Etching on copper

Dimensions: Platemark 175 x 156 mm, 7 x 6 1/8″; sheet 410 x 310 mm, 16 1/8 x 12 3/16″

Signature: Signed “Picasso” in bold, thick pencil in the lower right; inscribed “46/50” by another hand in the lower left

References: Bloch 256;

Baer 295 Bb1;

Fryberger, Picasso: Graphic Magician, p. 63;

Baer, Picasso the Engraver, p. 54 and 72;

Baer, Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection, p. 71;

Müller, Pablo Picasso and Marie-Thérèse Walter: Between Classicism and Surrealism, p. 93

Ingrid Mossinger, et al., Picasso et les Femmes, Kunstsammlung Chemnitz, Dumont, p. 181

Edition: Numbered 46 of 50; published by Leiris in 1961 without steelfacing before the cancellation of the plate. Fifteen artist’s proofs were published at the same time.

Paper: Tinted Arches laid paper with a lovely creamy hue (“vergé d’Arches teinté” -Geiser/Baer); untrimmed, deckled edges on all sides

Provenance: Private collection, France

Impression: Unusually strong

Condition: Excellent; slight waviness of the lower left margin; uncirculated and never before framed until now

Price: Upon request

The long list of literature references above evinces the enthusiasm of art historians for this Picasso. Brigitte Baer featured it in both of the exhibition catalogues she authored for two landmark Picasso print retrospectives. Of late, collectors have been catching up, as their interest in this etching appears to have markedly increased. In just the last several months (at the time of this writing), we sold another impression twice, and I know of another recent sale in NY. That’s a lot for such a small edition. We also recently parted with an impression of the related Tête de Femme (B250), also an exceptional though much pricier artwork and, some time before that, we sold the frontal view entitled Tête de Face (B276). Though I have long loved the etching at hand above all others in the Marie-Thérèse sculptural series, collectors’ fascination with this piece as well as with B250 is apparently the result of the recent blockbuster Picasso Sculpture exhibit at the MOMA, which included it as well as a number of related sculptures. This renewed interest was compounded by the media prominence of a lawsuit between Maya, Qatar, and Gagosian. Maya allegedly double-sold a large and wonderful plaster in the corresponding sculptural series:

The suit was settled in 2016, four months after the show had ended, in Gagosian’s favor, who in turn sold it to the famous Picasso collector, Leon Black. Gagosian had agreed to purchase it for around a $106M, but Maya had allegedly already agreed to sell it to Qatar for &42M. Reportedly it was one of Maya’s faves, and I do not know why she parted with it. This very plaster, as well as a number of other sculptural greats in the series, were on view the year before at that MOMA show. (There was an excellent accompanying exhibition catalogue.) The flurry of recent sales of the etching at hand, as well as the related B250 etching are my most direct ways to gauge the general interest in this sculptural series. By contrast, in all the 14 years since the inception of our dealership, we sold but one of these etchings, yet another impression of the etching at hand. It is likely that the MOMA exhibit, as well as the re-opening of the Picasso Museum in Paris, which has a number of these sculptures on permanent view, have piqued the interest in this amazing sculptural series.

Picasso created other equally great sculptures before and after, such as the baboon bronze made of two toy cars, or the she-goat tethered in the courtyard at the MOMA (another cast is on view at the Picasso Museum Paris)—you can fill in the blanks with your other favorites, but they were generally one-offs. The Marie-Thérèse sculptures, however, comprised Picasso’s greatest sculpture series.

After a two-decade hiatus from sculptural modeling, Picasso began this series in 1928 but quickly realized he needed more space. He also desired some privacy for himself and his new mistress Marie-Thérèse, away from his estranged wife Olga. So two years later he purchased a chateau for this dual purpose. It was located in Boisgeloup, a town not far from Paris. There was a stable on the property, which he converted into a sculpture studio, where he channeled a great burst of creativity into plaster over the next two years and gave birth to a large number of fantastical humanoid sculptures loosely based on his muse. By 1933, Picasso’s paintings, drawings and prints of the period had become a self-reflective celebration of these sculptures, and the sculptor’s studio became their principal subject. The Vollard Suite featured many takes on the sculptor’s studio, often combining neoclassical representations of the sculptor and his model alongside graphic representations of this surrealist sculpture series. But he also created several closeup etchings and drypoints of the sculptures themselves. The tour de force at hand is Picasso’s most accomplished rendering of a sculpture in a two-dimensional medium.

Only Picasso could manage to so utterly lay bare the soul of his muse, despite such extensive anatomical distortion, or perhaps because of it. For all her altered features, Marie-Thérèse still manages a demure, introspective look with her stony, sightless, inwardly directed eye and her sensitive lips. What’s especially wondrous about this artwork is that Picasso managed to convey such tenderness–with sausages. All the while, his subject engages the viewer, seemingly asking, “Yeah, right–you say there’s a what on the top of my head?”

If my experience of this artwork is at all like that of the typical viewer, when looking at it, I first grok that the subject is a woman in profile. At the same time, I can’t help but notice that her features are grossly distorted. I eventually make my way to her lips, which are rendered more tenderly and more realistically than the remainder of the composition and, with the nearby cheek and chin and even the bottom of the nose, create an emotional focal point that humanizes and feminizes the entire composition. Without these semi-realistic features, this would have been an abstract composition only arguably representing a human head. It took Picasso’s genius to make this inventively bizarre head seem nonetheless feminine and human. It amuses me to wonder whether you the viewer experienced this artwork similarly, or whether its creator did. Picasso claimed (in so many words) that much of his process was subconscious, so I’m not implying that this was necessarily his conscious intention. But by this point in the artist’s life, he had been sensualizing his female portraiture for decades.

This woman’s head represents one of Picasso’s many styles of the period which were collectively termed Surrealism, the cutting-edge movement in art of the time. Though Picasso refused to publicly ally himself with this movement, he was clearly its inspiration and its vanguard. As André Breton, who is best known as the principal founder of surrealism, conceded, “Surrealism, if it tends to define a line of action, simply has to go where Picasso has gone, and where he will return” (quoted in C. Piot et al., The Ultimate Picasso, New York, 2000, p. 232). Sir Roland Penrose described the radicalism of Picasso’s surrealism in the context of his previous work as follows, “These excursions into realms formerly forbidden by a canonical respect for beauty were more profoundly disturbing than the attacks made by Cubism on academic conceptions of painting. They upset man’s vision of himself which had sprung from classical tradition. But we were to discover, thanks to Picasso, that the image of man did not reside only in an ideal conception, but that in its nature it should be organic and alive.” (Picasso: Life and Work, Berkeley, 1981, pp. 255-256)

As is readily apparent from the rather long list of references above, this magnificent artwork has been included in every general survey of Picasso prints, at least those in our library. It is significant on several levels. In 1931 and -32, Picasso developed a sensational, unique style, one more in a chain of innumerable unique styles, in which Marie-Thérèse’s facial features were modeled in plaster with exaggerated, thick, rounded forms, which have been likened to ropes or sausages by various writers. The results in plaster and later in bronze were magnificent and compelling. About twelve months later, in February and March, 1933, Picasso made several etchings of Marie-Thérèse’s head, including this one, that look very sculptural and are in fact modeled in the same style as the recent plasters. Two of these, Bloch numbers 250 and this one, 256, are simply amazing works. That Picasso could create such shapes out of plaster was amazing enough, but that he could imbue their two-dimensional representations on paper with such sculptural volume was in and of itself incredible.

Soon after creating these works, Picasso began incorporating similarly modeled heads onto full-length figures of models in etchings of the sculptor’s studio, or into the form of sculptures within the studio. These prints were later grouped into the Vollard Suite in a far larger edition. (See, for example, Bloch numbers 146 and 219, illustrated as Figures 13 and 18 in Chapter 6 of A Guide to Collecting Picasso’s Prints on this website. Other examples include Bloch numbers 148-158, 176 and 218.)

Tête de Femme is also unusual because it is perhaps the only Picasso print, in addition to his lithographic fingerpainting (Paloma et Claude, Bloch 664, see elsewhere in this catalogue) in which not only is the artist’s creation absolutely charming, but also his technique itself is charming. In creating this portrait, Picasso used his mistress’ nail polish as a sort of resist with which he drew directly onto the raw copper plate. Then, a prolonged dip in acid lowered the surface level of the copper plate everywhere except where the nail polish had been applied, yielding a “negative engraving” in which the image, rather than engraved into the plate itself, is presented in relief, such that everything other than the image would get the printer’s ink. Baer refers to the medium of this print as an etching, but that is likely because the actual technique, unique in this application yet somewhat akin to aquatint, has yet to be named. The result of this unique printmaking process is that this is one of the most beautiful–and beautifully printed–Picassos of all.

This 2-D “sculpture” seems poised to attain the same popularity as the earlier, more realistic portrait of of Marie-Thérèse, the 1928 lithograph entitled Visage (B95). Picasso created Visage within a year or so of their first meeting, when he was more inclined to portray his lover realistically. But, true to form, Picasso wouldn’t play it straight for long—just five years later and the subject is barely recognizable. We can ID her only by the hints at her short hair and aquiline nose. Like Visage, an artwork of similar size, this later portrait is printed dark and bold, so that Marie-Thérèse is well seen from across the large room, which she nonetheless commands at a distance of 20 feet. Yet at an edition size one-fifth of Visage, this Tête de Femme, especially in desirable condition, is much harder to find. And, however charming Visage is, we don’t really need Picasso for his realistic portraiture. We most certainly do need him for his inventiveness!