(hand-colored, Bloch 847)

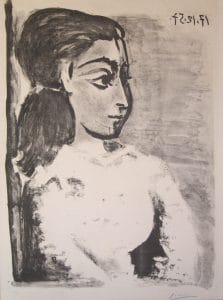

Another muse, another style. Or several. Picasso met Jacqueline Roque in 1953, and she became his main squeeze the following year, after Françoise had left him. Jacqueline remained with Picasso for the last 20 years of his life, became his second wife, and was the subject of more of his works than any other woman. In printmaking, Picasso applied his full panoply of tricks to his new muse, including etchings, aquatints and lithographs, and developed his mastery of linoleum cuts, finally delivering a measure of color to his color-starved audience.

Table 25. 1955-1956

| Bloch # | 780 | 782 | 788 | 789 | 791 | 794 | 795 | 800 | 801 | 804 |

| Beauty | * | ** | * | ** | ** | * | ** | * | * | *** |

| Significance | * | ** | ||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | ***** | *** | *** | *** | * | |||

| Size | ***** | * | ** | ***** | **** | **** | **** | * | **** | * |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | * | *** | ***** | ** | *** | ** | ** | ||

| Color | *** | ** | *** | |||||||

| Fading | ***** | * | ||||||||

| Cost | *** | * | ? | ** | ** | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | N | ? | Y | Y | P | N | N | Y | Y/N |

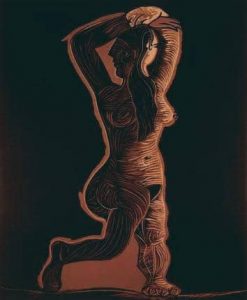

Corsage Blanc (Bloch 848)

This lithograph, one of the three best of Jacqueline, most tenderly depicts her countenance and, with a few bold brushstrokes, brings out her sensitivity and intelligence so convincingly that the viewer feels he almost knows this woman.

Interestingly, Picasso returned to this same zinc twice over the next twelve months. He presumably was dissatisfied with the appearance of these last two states, because they were not editioned. (Mourlot and Cantz say that the second state was not printed at all, though somehow a photo of it is shown in Cantz. The third state is illustrated in Mourlot.) One must be thankful, therefore, that Picasso saw fit to print the edition of this lithograph before he irrevocably altered it and became dissatisfied with his results. How often one wishes that he had done so with earlier states of other prints, when one or more of those earlier states seem superior to the final, editioned state. In this rare instance, we are grateful that Picasso perceived the beauty of the first outpouring of his vision onto the zinc and memorialized it on paper. Just as this is one of Picasso’s loveliest prints, at almost 70 cm it is one of his largest.

Table 26. 1956-1957

| Bloch # | 826 | 827 | 830 | 833 | 834 | 835 | 836 | 846 | 847 | 848 |

| Beauty | * | *** | ** | * | * | ** | ** | * | ***** | **** |

| Significance | * | ** | * | * | * | * | * | ***** | **** | |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Size | **** | **** | **** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | |

| Visibility at a distance | ** | *** | *** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** |

| Color | * | * | */N | |||||||

| Fading | * | * | */N | |||||||

| Cost | ** | ** | * | ** | * | * | * | *** | **** | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Signature | Y | Y | P/Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Table 27. 1957-1959

| Bloch # | 849 | 850 | 852 | 853 | 854 | 859 | 871 | 898 | 901 | 907 |

| Beauty | * | ** | *** | * | *** | **** | * | * | * | *** |

| Significance | * | ** | *** | * | *** | ***** | * | *** | ||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | ***** | ***** | **** | **** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | *** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | *** | ** | ***** |

| Color | **** | *** | ||||||||

| Fading | *** | ** | ||||||||

| Cost | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ***** | * | * | * | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

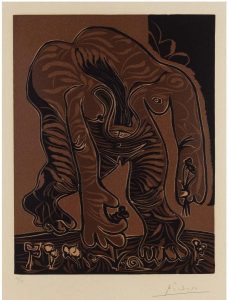

At this point in time we start getting into Picasso’s linoleum cuts, aka linocuts. The technique Picasso employed to create them deserves special mention. As you can see, I have deliberately avoided bogging you down in the technical details of printmaking. I envisioned your eyes glazing over, and then your head slumping forward onto the “Buy this now!” key. Though many of the complexities of Picasso’s printmaking techniques remain unknown, his linocuts are rather well understood. But to understand the technique is certainly not to demean his accomplishments. On the contrary, this understanding only serves to increase our awe of his artistic abilities. Here’s a brief explanation of the technique, so you can see what I mean.

The first linocut in colors that Picasso created is the impressive but pricey Buste de Femme d’apres Cranach (Bloch 859, 1958). He gouged a different linoleum plate for each color and came up with a rather masterful print, albeit one with a bit of misaligned registry between the several plates. Rather than improve his registry skills, he undertook the greater challenge of using the same piece of linoleum for each successive color. Linocuts are a reductionist technique much like woodcuts, though the medium is softer and therefore easier to gouge. You gouge out the parts you don’t wish to be inked. What’s left in relief on the plate is what gets the ink. (This is the opposite of so-called intaglio prints such as etching, drypoint, and aquatint, in that the depressions on the copper plate trap the ink and transfer it onto paper.) In Picasso’s case the final print was created from only one plate, regardless how many colors he used. Here’s how he did it. He first carved the plate, and then the entire edition was printed with the first color. (In many cases, the paper had been first printed with a background color prior to any cutting of the linoleum.) Then Picasso reworked the plate, and what was left still standing in relief was inked with another color and printed yet again onto the entire edition. This process was repeated as many times as the number of colors. Picasso’s genius was the ability to maintain the finished design in his mind throughout the process, because each successive reduction obliterated details of the design from the plate. Accordingly, the final states of the plates, which still exist, often bear little discernable resemblance to the overall design.

Picasso’s linoleum shortcut has been widely considered unprecedented, but word has it that the technique was invented by a German artist and taught to Picasso (personal communication).

Table 28. 1959, Linocuts

| Bloch # | 908 | 909 | 910 | 911 | 915 | 922 | 923 | 928 | 930 | 931 |

| Beauty | ***** | **** | ***** | **** | * | ***** | * | ** | **** | ***** |

| Significance | ***** | **** | ***** | **** | * | ***** | **** | ** | **** | ***** |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** | ***** |

| Color | ***** | *** | *** | *** | **** | **** | **** | ** | **** | ***** |

| Fading | **** | *** | *** | *** | * | * | * | ** | ** | ** |

| Cost | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | **** | **** | *** | *** | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Table 29. 1959-1960, mostly linocuts

| Bloch # | 932 | 934 | 935 | 936 | 938 | 939 | 949 | 979 | 982 | 983 |

| Beauty | * | *** | * | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | |

| Significance | * | *** | ** | ** | *** | *** | ** | * | * | |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ***/- | *** | **** | *** |

| Size | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ** | ** | * | * |

| Visibility at a distance | **** | ***** | ***** | **** | *** | ***** | ||||

| Color | *** | **** | **** | ** | * | * | * | |||

| Fading | * | ** | ** | * | * | * | * | |||

| Cost | ** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | */* | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | *** | *** | |||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y/N | ES | ES | ES |

Table 30. 1960-1961

| Bloch # | 984 | 985 | 995 | 1003 | 1004 | 1005 | 1006 | 1007 | 1009 | 1020 |

| Beauty | * | * | ** | * | *** | * | * | ** | ||

| Significance | ** | * | ||||||||

| Rarity | ***** | *** | *** | * | *** | *** | ** | *** | ||

| Size | ** | ** | ** | **** | **** | *** | ***** | ** | ***** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | ***** | ** | **** | * | **** | *** | |||

| Color | *** | |||||||||

| Fading | ** | |||||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | * | ** | |||||||

| Signature | N | ES | ES | N | N | N/Y | Y | Y | P | Y |

Table 31. Linocuts, 1961-1962

| Bloch # | 1023 | 1026 | 1027 | 1028 | 1063 | 1064 | 1065 | 1066 | 1067 | 1068 |

| Beauty | * | * | * | * | * | *** | **** | **** | **** | *** |

| Significance | * | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | **** | |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | **** | **** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** |

| Color | ***** | *** | ** | ** | *** | **** | **** | ** | ||

| Fading | ***** | *** | ** | ** | *** | ***** | **** | ** | ||

| Cost | ** | * | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Table 32, Linocuts, 1962

| Bloch # | 1069 | 1070 | 1071 | 1072 | 1073 | 1074 | 1075 | 1076 | 1077 | 1078 |

| Beauty | ** | **** | *** | * | *** | *** | ** | * | ***** | *** |

| Significance | *** | *** | *** | **** | **** | **** | *** | ** | ***** | *** |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | ***** | *** | *** | ***** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** | ***** | ***** |

| Color | ** | ** | **** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ** | * | * | ** |

| Fading | ** | ** | **** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ** | * | * | ** |

| Cost | *** | *** | *** | ***** | *** | *** | *** | ** | **** | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

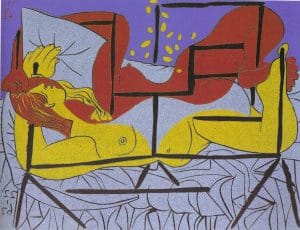

Danae is one of the most colorful Picasso prints, which represents Picasso’s interpretation of an ancient Greek myth. As the story goes, Danae was the daughter of Acrisius, the king of Argos. An oracle had foretold that Danae’s future son would slay his grandfather. In order to prevent this event from taking place, King Acrisius locked his daughter in an inaccessible tower, thereby removing her from contact with any potential suitors. Or so he thought…. The god Zeus, who always had an eye for female charms, was struck by the beauty of Danae, and desired her. Zeus therefore transformed himself into a shower of gold, and in this form impregnated Danae. The result of this union of human and divine was the great Greek hero Perseus. The myth of Danae has interested artists through the ages, including Caravaggio, Rembrandt, and Klimt. A joke of presumably similar vintage about the moral of this story, unfortunately told at the expense of the fairer gender, is that a sure-fire way to get to a woman is through gold:)….

Table 33, Linocuts, 1962

| Bloch # | 1079 | 1080 | 1081 | 1082 | 1083 | 1084 | 1085 | 1086 | 1087 | 1088 |

| Beauty | *** | *** | **** | **** | * | ***** | ***** | ** | * | **** |

| Significance | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ***** | **** | ** | ** | *** |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ***** | *** | *** | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | ***** | ***** | ***** | **** | ***** | ***** | *** | ***** | ***** |

| Color | *** | *** | ** | ** | ** | ***** | ** | *** | ** | ** |

| Fading | *** | *** | ** | ** | ** | **** | ** | *** | ** | ** |

| Cost | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | **** | *** | ** | *** | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | ** | * | |||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Flous (B1079)

For a discussion of Figs. 41 and 41b, see the webpage in our catalogue.

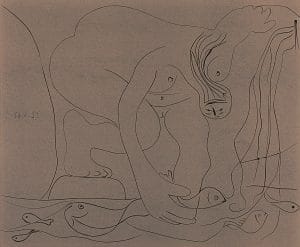

des Truites à la Main

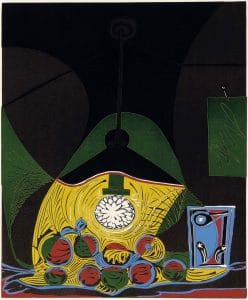

la Lampe (Bloch 1102)

Nature Morte sous la Lampe (Fig. 41a.) is one of the two finest still lifes that Picasso created in the linoleum cut medium. They are both stunningly beautiful, and it is hard to choose between them. The more brightly-colored horizontal one (B1101) is considerably more expensive, but I personally value the image at hand at least as much. Its beauty is more subdued, perhaps, but I find its magnificent composition very captivating.

Table 34, Linocuts, 1962

| Bloch # | 1089 | 1090 | 1092 | 1093 | 1095 | 1096 | 1097 | 1098 | 1101 | 1102 |

| Beauty | *** | * | **** | **** | * | * | * | ** | ***** | ***** |

| Significance | *** | * | *** | **** | * | *** | *** | *** | ***** | ***** |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | *** | *** | *** | ***** | *** | *** | ***** | **** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | **** | *** | **** | **** | *** | **** | ***** | ***** | **** |

| Color | **** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | **** | **** | **** |

| Fading | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | **** | **** |

| Cost | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | ***** | ***** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | * | ||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

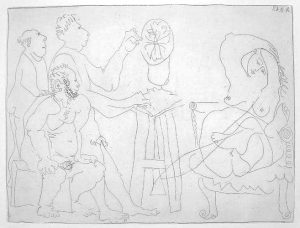

The artist’s studio had been Picasso’s favorite theme in the Vollard Suite, but he then largely forgot it apart from several prints in the mid-fifties as well as one in 1962. In 1963, Picasso renewed his printmaking interest in the artist’s studio, devoting no less than twenty-nine prints to it that year, with an ebbing stream of others through 1971, the last year he created a print. Atelier du Sculpteur (Fig. 41c, Bloch 1118) is one of the most accomplished and humorous of the lot. The model is depicted tenderly and gracefully, albeit in a wholly immodest and unselfconscious pose. The aged sculptor, hinting at the sexual impotence that marked Picasso’s waning years, is intently creating an abstract work of art that doesn’t even begin to resemble the model. The spectator behind the sculptor is straining to see the work in progress over the artist’s shoulder, whereas the other spectator is interested not so much in the sculpture as in the winsome model, upon whom he brazenly stares.

The abstract sculpture in the artist’s studio is reminiscent of a series of illustrations that Picasso created in 1931 for a deluxe edition of Balzac’s novel, Le Chef-d’Oeuvre Inconnu, The Unknown Masterpiece. (See Ch. 5, Fig. 10 and the related discussion for this story line.) By the time Picasso revisited this theme in the 1960’s, the art world had changed considerably. Unlike Frenhofer’s friends, who just pitied him, the spectators in the sculptor’s studio are awestruck by the artist’s sculpture, at least when not distracted by the nude. Abstract art had become mainstream and thus would have been a perfect target for Picasso’s expansive humor. Although Picasso had occasionally approached abstraction, especially in printmaking, he generally avoided it in favor of styles which highlighted his graphic mastery. He certainly would have considered abstract art fair game. He probably would have enjoyed the New Yorker cartoon, in which one guest at an art gallery opening, wine glass in hand, grouses to another, “I can’t imagine bringing a child into the current art world!”

Table 35, 1963

| Bloch # | 1111 | 1117 | 1118 | 1121 | 1139 | 1141 | 1142 | 1143 | 1144 | 1145 |

| Beauty | ** | * | *** | ** | ** | * | ** | * | * | ***** |

| Significance | ** | ***** | ||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Size | **** | **** | **** | **** | ** | **** | ** | *** | *** | **** |

| Visibility at a distance | * | * | * | *** | *** | **** | ***** | |||

| Color | ***** | |||||||||

| Fading | **** | |||||||||

| Cost | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * | **** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Table 36, 1963-1964

| Bloch # | 1147 | 1148 | 1149 | 1155 | 1157 | 1158 | 1159 | 1181 | 1185 | 1189 |

| Beauty | *** | *** | **** | * | * | * | ** | * | * | *** |

| Significance | *** | *** | **** | *** | ** | |||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |||

| Size | **** | **** | **** | ** | **** | **** | ** | **** | *** | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | ***** | ***** | * | *** | *** | ** | ***** | *** | **** |

| Color | ** | ** | **** | |||||||

| Fading | ** | ** | **** | |||||||

| Cost | *** | *** | **** | * | * | * | * | *** | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ||||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/Y | N/Y |

Table 37, 1958-1966

| Bloch # | 1232 | 1244 | 1245 | 1246 | 1248 | 1254 | 1255 | 1267 | 1276 | 1282 |

| Beauty | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * |

| Significance | * | * | ||||||||

| Rarity | *** | * | * | * | * | * | * | *? | * | |

| Size | **** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ***** | ***** | ***** |

| Visibility at a distance | ** | ***** | ***** | |||||||

| Color | * | ***** | *** | |||||||

| Fading | *** | *** | *** | |||||||

| Cost | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | ** | ||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | N | Y/N | Y/N |

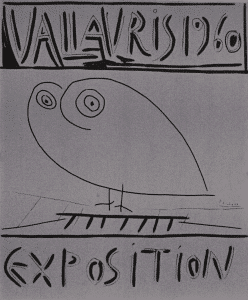

Exposition (Bloch 1290)

Stripped to its bare essence, the elimination of just one more design element would render this bird unrecognizable. Yet even my three-year-old recognizes this as an owl. Part of the charm of this design, however, is that it makes you wonder, how? What’s the tip-off that it’s an owl? It’s “owlishness” somehow enters our subconscious without our awareness of what exactly it is that convincingly makes it an owl. Yet Picasso’s genius was that he understood this cognitive process on a conscious level and was, at will, able to bring just enough detail, but no more, to his design to conjure the desired image in our mind. This style of art could be called “Reductionism”, one of the hundreds of unique styles which Picasso invented. This lovely owl follows a long line of reductionist masterworks by the artist, perhaps most famously the sculpture of 1942, Tête de Taureau, which was fabricated by the simple juxtaposition of an old bicycle seat and handlebars.

Picasso kept many animals, one of which was a wounded owl that he found and nursed back to health. It served as the inspiration for several prints, as well as a number of beautiful paintings, sculptures, and drawings.

The model in the above composition is tenderly portrayed, content in her repose and with a smile on her face. The contrastingly masculine visage of the painter is depicted with a sentient mouth and a post-cubist rendering of both sides of his nose. He may be resting leisurely on his elbow, but his eye is focused on the model and his mind is seriously intent upon the task at hand. As he applies his brush to a fresh canvas, the painter examines his model with an oversized pupil and stern brow comprising a mirada fuerte, the classic “strong gaze” of the Spanish for which Picasso himself was noted. Although the composition is very reminiscent of the sculptor’s studio images which formed the dominant theme of the Vollard Suite three decades earlier, the style is quite different. The precise neoclassical line of the etchings of the ‘thirties has however been replaced by bolder, thicker, looser lines achieving the painterly effect such that they resemble brushstrokes. The chiaroscuro of this richly inked print represents a technical tour de force, in which Picasso used unusual materials and methods in creating the aquatint’s tonality, including a lithographic crayon, prior to etching and using a drypoint to enhance the contours and other lines of the image.

Table 38, 1960-1966 (note the late Bloch numbers in the next table below)

| Bloch # | 1290 | 1370 | 1371 | 1372 | 1375 | 1376 | 1377 | 1378 | 1385 | 1389 |

| Beauty | *** | **** | * | * | * | ** | ** | **** | **** | * |

| Significance | ** | *** | * | ** | * | |||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Size | ***** | ***** | **** | **** | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | *** |

| Visibility at a distance | ***** | **** | *** | *** | *** | *** | **** | ***** | **** | *** |

| Color | **** | |||||||||

| Fading | * | |||||||||

| Cost | * | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | *** | ** | ** | **** | **** | |||||

| Signature | Y/N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Table 12a. 1934-36 and 1939, Late Bloch numbers (reprinted from Chapter 6)

| Bloch # | 1328 | 1329 | 1330 | 1333 | 1335 | 1336 | 1337 | 1338 | 1339 | 1340 |

| Beauty | *** | *** | *** | ***** | **** | *** | * | * | ***** | * |

| Significance | *** | *** | *** | ***** | **** | **** | *** | *** | ***** | *** |

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | ***** | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Size | ** | ***** | ***** | ***** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | * | *** | ***** | *** | ***** | **** | ***** | ***** | ||

| Color | ***** | ** | ***** | ** | ** | ** | ||||

| Fading | *** | ** | *** | ** | * | ** | ||||

| Cost | * | ** | ** | ***** | **** | ** | *** | ** | ? | *** |

| Desirability to cost ratio | * | * | * | |||||||

| Signature | ES | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N |

Table 39, 1966

| Bloch # | 1390 | 1394 | 1400 | 1401 | 1404 | 1405 | 1446 | 1459 | 1467 | 1473 |

| Beauty | * | **** | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Significance | ** | * | ||||||||

| Rarity | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | * |

| Size | *** | **** | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** |

| Visibility at a distance | *** | **** | *** | *** | *** | ** | * | * | ||

| Color | ||||||||||

| Fading | ||||||||||

| Cost | * | ** | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Desirability to cost ratio | ** | |||||||||

| Signature | Y | Y | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | N | N |